Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

Long Live the Majestic Vase

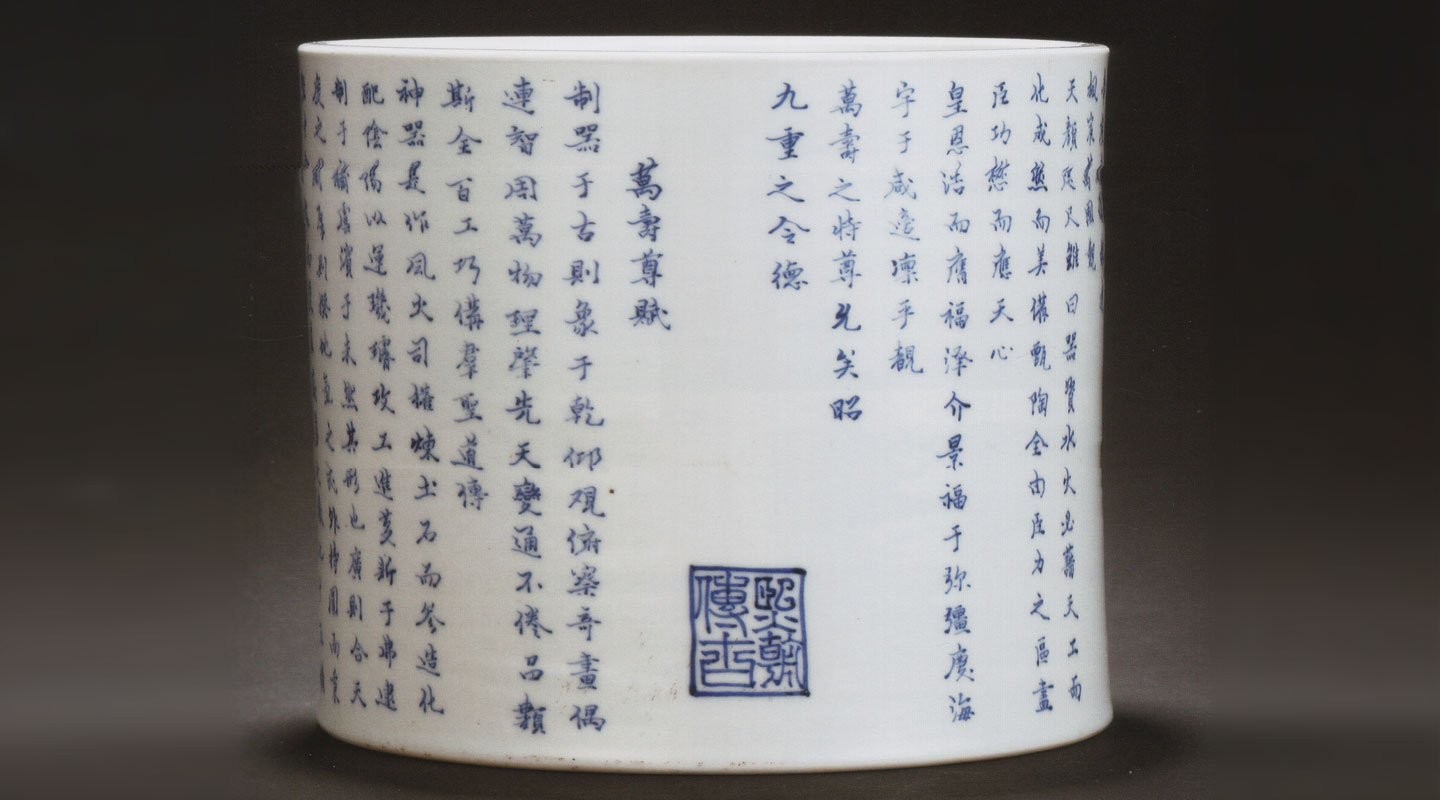

Positioned squarely in the middle of the museum gallery, the monumental blue-and-white vase has an aura that is undeniably imperial. Inscribed with precisely 10,000 characters, all but one of which are variations of shou(壽)—which means longevity, the vase is emphatically auspicious. These shou characters appear in three sizes. While the large and mid-sized characters vary in design, some small characters are written in identical style. More interestingly, the arrangement, selection, and variation of the small characters follow some sort of pattern.

The auspicious meaning of the vase is further enhanced by the fact that the one exceptional character—not of shou—turns out to be wan(萬), which means ‘ten thousand’. This prodigious number is only eclipsed by the vase’s whopping market value in 2013, when a comparable work was auctioned for over 64 million dollars at Christie’s, which duly referenced the CUHK vase and the research of our esteemed former director Prof. Peter Lam. Professor Lam has heralded the vase as the ‘iconic treasure of the museum’ upon its accession in 1999.

Still, this rare treasure remained little known for a long time. Around 1951 or 1952, prominent businessman and philanthropist Sir Quo-wei Lee chanced upon it in a London antique shop and acquired it for 300 pounds, which was less than the cost to ship the vase back to Hong Kong. Local connoisseurs, who preferred imperial wares inscribed with reign marks, believed it to be an export ware or Vietnamese ware. The vase was relegated as an umbrella stand for the next few decades, until an exhibition of artworks from the Palace Museum in the early 1980s showed an almost identical work, which prompted Sir Quo-wei to invite the Palace Museum expert to authenticate his vase. When the experts confirmed that it was the third piece in existence—other than the works in Beijing and Nanjing Museum, the once convenient umbrella stand was duly stored in a custom-made box. Sir Quo-wei donated the vase to the Art Museum on 9 September 1999, a date which curiously echoes the number of shou characters on the vase. Perhaps more auspiciously, the number nine puns with the meaning of everlasting longevity.

The dramatic life of the vase in recent memory is by no means the most fascinating aspect of this object. The paucity of documentation on this object intrigues scholars, and the uncertainty concerning it no doubt contributes to its appeal. While there is consensus among experts that it was a product of the Kangxi period, we have yet to find out exactly when and for whom it was made in the emperor’s long reign from 1662 to 1722. The textual content of ten-thousand shou suggests three possible occasions that called for the commissioning of the vase: (1) Chinese new year, (2) winter solstice, and (3) the emperor’s birthday. The vase was once believed to be made in 1713 for the Kangxi emperor’s 60th birthday. However, Professor Lam discovered and subsequently acquired in 2011 a brushpot that contains a long poem on the ten-thousand shou vase. As the brushpot can be dated to the early Kangxi period around the 1680s, and as the text on the brushpot provides a context for the manufacture of the vase, the vase is now believed to be made at around the same time. Current thinking leans towards 1683, a year in which the Kangxi emperor turned 30 and his grandmother the Grand Empress Dowager’s had her 70th birthday.

Since the 1980s, a few more wanshou vases have been discovered. It is probable that at least nine such vases were produced, since traditionally birthday gifts to the emperor should be presented in groups of nine or multiples of nine. Whether or not this number pertains to a set commissioned specifically for the emperor (or the grand empress dowager), we remain hopeful that future research will shed light on this intriguing masterpiece.

This article was originally published in No. 497, Newsletter in May 2017.