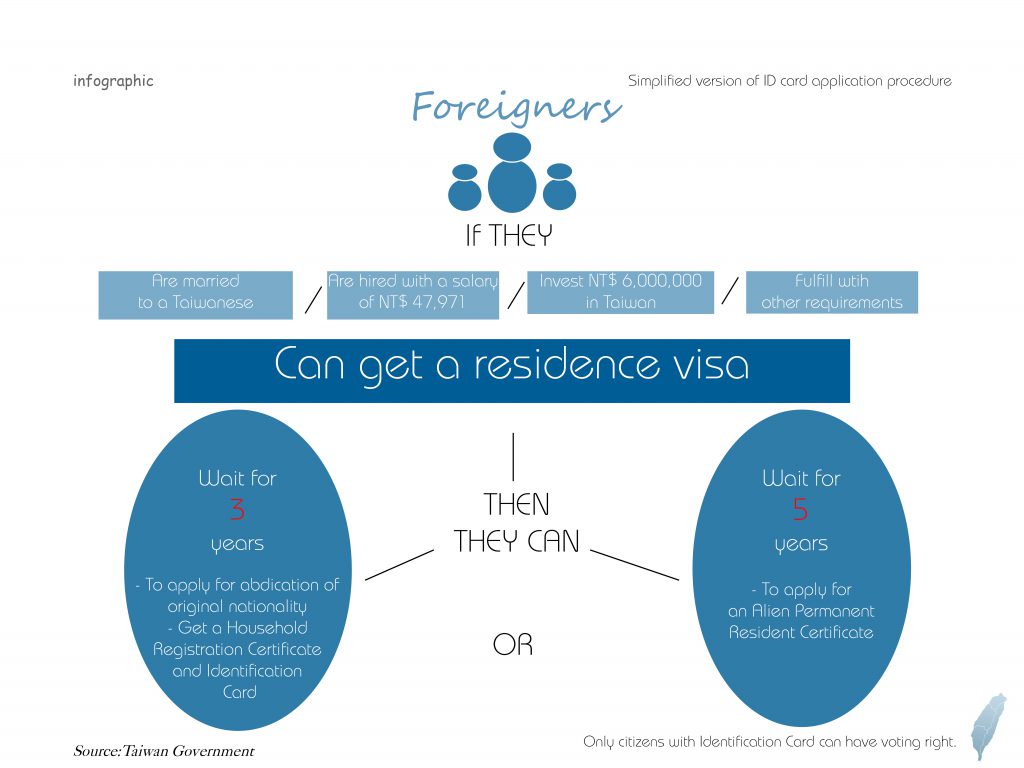

Many foreigners are not entitled to vote in Taiwan, as dual citizenship is not allowed

By Macau Mak & Stella Tsang

On the evening of January 16th, more than 20,000 supporters of Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) gathered at the party’s campaign headquarters in Taipei. They erupted in cheers and waved green flags as fireworks lit up the sky. “President Tsai, dong xuan!” they cried, proclaiming the victory of Tsai Ing-wen in the local Minnan dialect.

The election was a landmark because Taiwan not only elected its first female president but also gave the DPP its first majority in the island’s Legislative Yuan.

In the seaside town of Tamsui in the northern part of New Taipei city, customers at a small coffee shop watched these events unfold on their mobile devices.

Among them was 32 year-old Elias Gasparis, a Greek-Canadian raised in Canada, who enthusiastically followed and discussed the developments and results with his Taiwanese wife.

Gasparis, who teaches English in a local school and has lived in Taiwan for more than five years takes a strong interest in local current affairs. “I really want to be involved (in the election) because I have a daughter and my wife is pregnant,” says Gasparis. “I want to be able to have some say in this country where my family is living.”

Gasparis sees Taiwan as his long-term home and has applied for an Alien Permanent Resident Certificate for permanent residency after meeting the five year residency requirement. But even after he gets the certificate, Gasparis will not be able to vote because in Taiwan, only Republic of China (R.O.C.) nationals are allowed to vote. The government does not allow naturalized R.O.C. nationals to have dual nationality, and Gasparis wants to keep his Canadian citizenship.

Contrast this with Hong Kong, where under Article 24 of the Basic Law, foreigners can register to vote once they acquire permanent residency after living in the city continuously for seven years.

According to Taiwan’s National Immigration Agency, more than 700,000 foreigners had either temporary or permanent residency in Taiwan in December 2015. To become R.O.C. nationals, foreign residents have to first relinquish their original nationality. One of the reasons that few are willing to do so is because there are concerns that foreigners can only be “second-class citizens”. Gasparis mentions the case of a woman who became stateless after relinquishing her Vietnamese nationality, only to be stripped of R.O.C. citizenship in 2013 for having an extra-marital affair. Authorities deemed this to mean she had violated the requirements for morality stipulated in the Nationality Law.

Many local Taiwanese are not aware of the issues surrounding voting rights and complex nationality rules as they apply to foreigners. Gasparis recalls that during last year’s local election, some politicians visited his school. They only recognized what the issues were after foreign teachers explained them.

Another long-time resident in Taiwan who is keen to vote is American Kerim Friedman. Friedman has taught in the Department of Ethnic Relations and Culture of Donghua University for 10 years and actively participates in local social movements. But like Gasparis, he prefers to keep his own citizenship. “My parents are still there (America). I still have family there and I’m still connected to United States,” he says.

It is good that you shed some light on this important issue, but you missed a major point, that is, why can foreigners from China hold dual citizenship here while foreigners from elsewhere can not.