Many foreigners are not entitled to vote in Taiwan, as dual citizenship is not allowed

By Macau Mak & Stella Tsang

On the evening of January 16th, more than 20,000 supporters of Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) gathered at the party’s campaign headquarters in Taipei. They erupted in cheers and waved green flags as fireworks lit up the sky. “President Tsai, dong xuan!” they cried, proclaiming the victory of Tsai Ing-wen in the local Minnan dialect.

The election was a landmark because Taiwan not only elected its first female president but also gave the DPP its first majority in the island’s Legislative Yuan.

In the seaside town of Tamsui in the northern part of New Taipei city, customers at a small coffee shop watched these events unfold on their mobile devices.

Among them was 32 year-old Elias Gasparis, a Greek-Canadian raised in Canada, who enthusiastically followed and discussed the developments and results with his Taiwanese wife.

Gasparis, who teaches English in a local school and has lived in Taiwan for more than five years takes a strong interest in local current affairs. “I really want to be involved (in the election) because I have a daughter and my wife is pregnant,” says Gasparis. “I want to be able to have some say in this country where my family is living.”

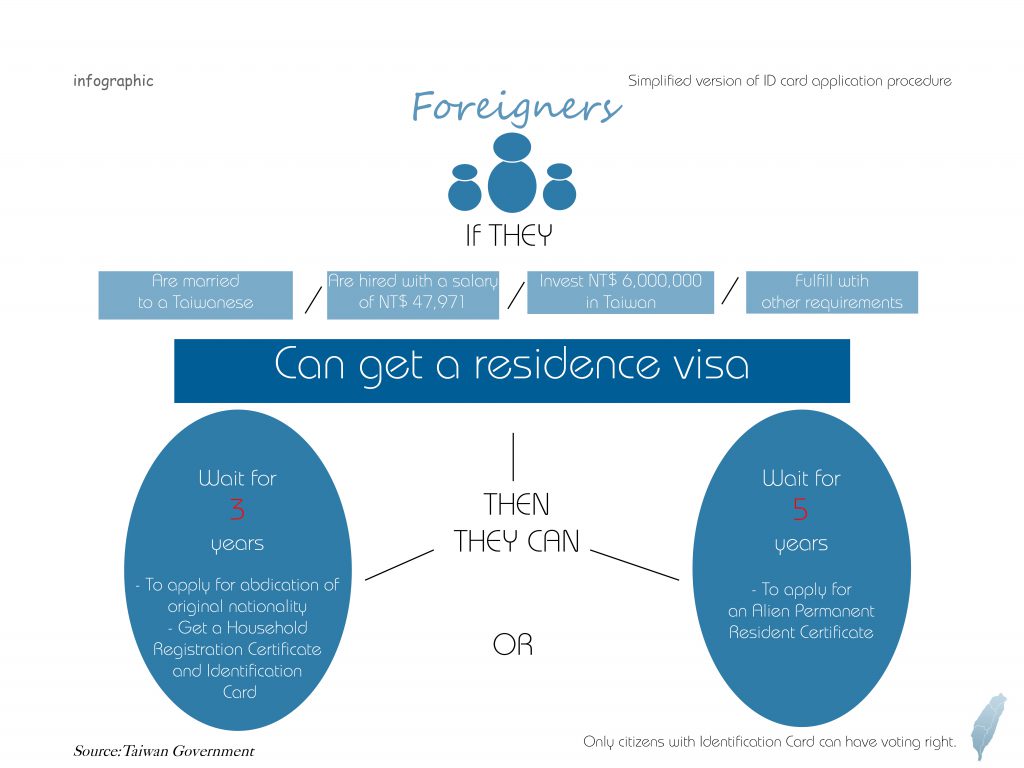

Gasparis sees Taiwan as his long-term home and has applied for an Alien Permanent Resident Certificate for permanent residency after meeting the five year residency requirement. But even after he gets the certificate, Gasparis will not be able to vote because in Taiwan, only Republic of China (R.O.C.) nationals are allowed to vote. The government does not allow naturalized R.O.C. nationals to have dual nationality, and Gasparis wants to keep his Canadian citizenship.

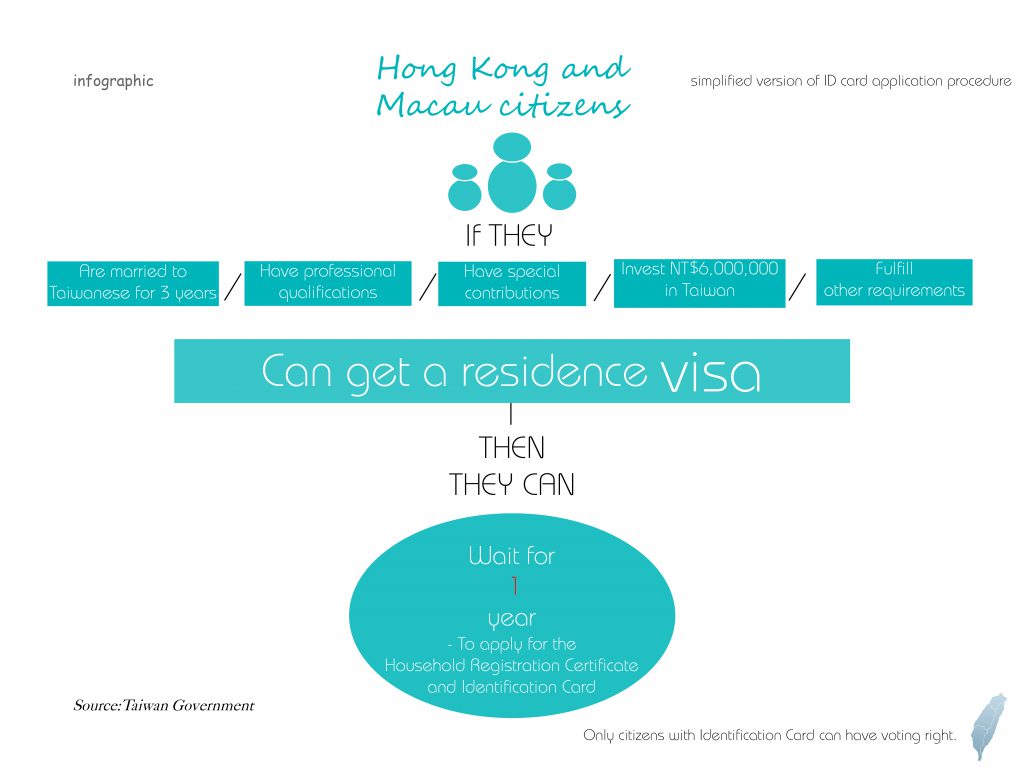

Contrast this with Hong Kong, where under Article 24 of the Basic Law, foreigners can register to vote once they acquire permanent residency after living in the city continuously for seven years.

According to Taiwan’s National Immigration Agency, more than 700,000 foreigners had either temporary or permanent residency in Taiwan in December 2015. To become R.O.C. nationals, foreign residents have to first relinquish their original nationality. One of the reasons that few are willing to do so is because there are concerns that foreigners can only be “second-class citizens”. Gasparis mentions the case of a woman who became stateless after relinquishing her Vietnamese nationality, only to be stripped of R.O.C. citizenship in 2013 for having an extra-marital affair. Authorities deemed this to mean she had violated the requirements for morality stipulated in the Nationality Law.

Many local Taiwanese are not aware of the issues surrounding voting rights and complex nationality rules as they apply to foreigners. Gasparis recalls that during last year’s local election, some politicians visited his school. They only recognized what the issues were after foreign teachers explained them.

Another long-time resident in Taiwan who is keen to vote is American Kerim Friedman. Friedman has taught in the Department of Ethnic Relations and Culture of Donghua University for 10 years and actively participates in local social movements. But like Gasparis, he prefers to keep his own citizenship. “My parents are still there (America). I still have family there and I’m still connected to United States,” he says.

Friedman says politicians ignore foreigners’ concerns and issues, including their voting rights, precisely because they do not have a vote and politicians only care about those who can vote for them.

He says the current system is unfair, as naturalized R.O.C. nationals cannot hold dual nationality but those who are born as R.O.C. nationals are permitted to do so.

Bruce Liao Yuan-hao, an associate professor at National Chengchi University’s College of Law says foreigners’ renouncement of their original nationality is traditionally viewed as “loyalty” to their new country.

He points out the concept of the “nation state” is embedded in Taiwan’s Nationality Act and Migration Act. He further explains nationalism was widespread after World War II, and most countries did not allow foreigners to hold dual citizenship, still less have voting rights. European countries only began to give foreigners with residency voting rights in local level elections after the establishment of the European Union. The United States followed suit in recent years.

The issue of foreigners gaining R.O.C. nationality came under the spotlight in recent years with the widely reported case of American Father Brendan O’Connell in 2012.

The nearly 80-year-old has served the disabled in Taiwan for over 50 years and decided to spend his remaining years there. As O’Connell did not wish to relinquish his original nationality, he asked to be allowed to hold dual citizenship. That year, the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) submitted an amended draft of the Nationality Act to the legislature to permit foreigners with distinction and special talents to hold dual nationality.

However, the draft has yet to begin its passage through the legislature process because of the different political parties failed to agree on initiating the process.

There have been other attempts to relax legislation on nationality and voting rights for non-nationals. In 2007, Liao negotiated with legislators to find a way to allow foreigners with permanent residency to vote in local elections. That too failed but Liao says he understands the issue is sensitive in Taiwan. There are underlying fears that such reforms could open the door for recent migrants from Mainland China to vote and potentially influence Taiwan affairs.

The Republic of China in Taiwan was established in after the Kuomintang (KMT) lost in the Chinese Civil War to the Communist Party in 1949. The KMT declared martial law on the island, which was not lifted until 1985, and during this period the Taiwan found itself isolated from the outside world.

Liao says that before it began to open up and foreigners began coming to Taiwan in the 1990s, Taiwan was “an island that didn’t consider the entry of foreigners”.

With the lifting of martial law, the rise of local social movements and democratic reform, the Taiwanese began to consider their “national identity”. Given the often tense relationship between Taiwan and the Mainland, the controversial issue of voting rights for Mainlanders is brought up every time the question of voting rights for foreigners is raised.

But for Liao, voting rights are basic human rights and should be enjoyed by all residents. “There are so many of them (foreign migrants), but they can’t affect politics, so they would then be forgotten during the policy-making process,” he says. Liao says immigrants should stand up to negotiate with political parties and legislators; otherwise, their voices will be ignored.

One party that has listened to such voices is the Trees Party, founded in 2014. After being invited to attend a forum by immigrant pressure groups, the party included policies supporting foreigners’ voting rights in their election platform. Chief Strategy Officer Pan Han-shen says this was a direct outcome of the forum, but he notes the big parties do not care much about such events.

Yet Trees Party candidates rarely discussed the issue with supporters due to the complicated historical context. More tellingly, Pan says Taiwanese generally discriminate against foreigners, especially South East Asians. “Taiwanese seem to be nice to foreigners, but meanwhile, discriminate against them,” he says.

He adds Taiwan locals are more likely to support legislation to give more rights to foreign white-collar workers, but not to blue-collar workers, most of whom come from countries in South East Asia.

Most South East Asian migrants in Taiwan are foreign spouses and blue-collar workers. Lisa Huang (who goes by the name Lisa), a 28-year-old Indonesian immigrant, has lived in Taiwan for eight years. South East Asian women who are married to Taiwanese husbands, like Lisa, are commonly called “foreign brides”. Lisa, who is a mother of an eight-year-old child, says she has experienced discrimination in the workplace and in her local neighbourhood.

She recalls that she once wore mask to work at a bakery. Not knowing Lisa’s nationality, her Taiwanese colleague treated her well. Once she discovered she was Indonesian, the colleague immediately ignored her. “She told me she hates foreigners,” Lisa says. “She thought South East Asians would rob Taiwanese of their jobs and men.” She adds that her husband and mother-in-law have been asked by their friends whether Lisa is greedy for money and whether she “behaves properly”.

This kind of discrimination has hindered immigrants’ social integration and political participation. Some of Lisa’s friends have obtained R.O.C. nationality, but they do not vote, or if they do, they just follow their husbands’ voting preferences. “Taiwanese look down on us, and what we care is just to live well,” Lisa says.

Until four years ago, Lisa, like many of her peers, did not care about politics. At that time, a friend brought her to the People’s Democratic Front, an association advocating for minority rights. After she joined the association’s activities, Lisa learnt about various social issues and the significance of political participation. After understanding that issues such as food safety and her child’s education are affected by politics, she decided to get involved.

Encouraged by the People’s Democratic Front, she ran in the last Legislative Yuan election on a joint list with 44 other candidates in the Daan constituency in Taipei. Under this novel idea, 45 candidates decided to jointly ran for one seat, with one of them registering as the official candidate. In this way, Lisa could “stand” without being eligible to do so.

Although they eventually lost the election, Lisa continues to participate. She will give up her Indonesian nationality to apply for Taiwanese citizenship soon. Although Lisa is attached to her Indonesian nationality, she has decided to relinquish it after reflecting on the right to vote and to be elected.

But even after becoming a national, she would still have to wait 10 years before she could officially stand for election in Taiwan. Apart from casting her first vote, Lisa wants to highlight how immigrants’ right to be elected is restricted and is considering running in the next election to raise awareness of the issue.

Unlike the immigrants married to Taiwanese, some blue-collar workers, mainly working in menial and dangerous jobs, or as domestic workers, can never become R.O.C. nationals and can only stay in Taiwan for a maximum of 12 years. There were 587,940 such migrants in December, 2015.

The Taiwan International Workers’ Association (TIWA) has advocated for migrant workers’ rights since 1999. Its researcher Wu Jing-ru says the lack of translations of information about government’s services and current affairs, and long working hours prevent blue-collar workers from understanding Taiwan society, let alone participate in politics.

Wu believes migrant workers should have voting rights even if they are not citizens because labour policies strongly affect them. “Regardless of whether they are white-collar or blue-collar workers, it is ridiculous that migrants have no right to express their opinion in labour issues,” says Wu.

Foreigners’ voting rights in Taiwan are an issue of human rights, but it has received little attention worldwide. Wu explains that Taiwan is not a member of the United Nations. Therefore, it is not monitored by the UN or bound by the relevant international conventions.

In cooperation with other pressure groups, TIWA has organised large-scale protests every two years since 2003 to draw the attention of political parties and the general public on migrant rights. “People used to think that migrant workers steal their jobs, but their mindset is changing,” she says.

She has noticed that more workers are willing to join the protests in recent years and says recent rallies have targeted the DPP, as the likely ruling party after the January election.

Photo courtesy of TIWA

Despite the change in government, National Chengchi University’s Bruce Liao does not expect any changes on voting rights for non-nationals in the short term. He says that as a comparatively nativist party, the DPP is unlikely to treat it as a priority, especially with many pressing economic and trading issues needing attention. However, Liao does not think the issue will backslide either because the DPP is seeking ways to boost the economy. He explains that attracting and keeping more overseas professionals and business people can help to enhance the economy’s competitiveness. This may be a possible factor for the DPP to review foreigners’ voting rights in the long run.

Public opinion will also play a major part. “In 2000, Taiwanese are quite hostile to foreigners,” Liao says. “But in the recent ten years, citizens begin to view them positively and the government will gradually change its stance.”

It is good that you shed some light on this important issue, but you missed a major point, that is, why can foreigners from China hold dual citizenship here while foreigners from elsewhere can not.