Buildings lie empty despite a shortage of school places in the northern New Territories

By Emily Chung and Natalie Tsoi

The roof has collapsed, the windows are shattered, trees and foliage have taken over. Except for the crumbling walls and doorframes, there is little to show there used to be a school here.

Tucked away in the village of Wai Tau in Tai Po, Lam Tsuen No. 3 Public School closed 30 years ago. It was one of the 66 schools shut down before 2003, a group that represents around a third of the 172 school premises in Hong Kong to be closed and abandoned to date.

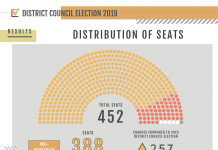

The year 2003 is significant because that was when the Education Bureau (EDB) launched a scheme to close and consolidate what it called “high cost and under-utilised” primary schools in response to a decline in the birthrate in preceding years. The total school age population aged between six and 11 years was estimated to drop from more than 493,000 in 2002 to around 410,000 in 2010.

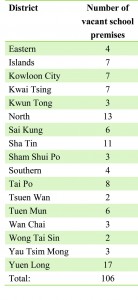

As result of the scheme, 106 schools have been shut since 2003, the majority of them in Yuen Long and North District. Meanwhile, 117 new school premises have been built to meet different demands in the same period.

Ironically, the districts hit hardest by school closures are those where school places are most in demand due to the growing number of cross-border students living in the Mainland but attending school in Hong Kong.

There were 3,500 cross-border students in all kindergartens, primary and secondary schools last year; that figure has risen to 16,300 this year. Meanwhile, the territory’s birthrate has continued to rise steadily since 2003.

Ip Kin-yuen, a Legislative Council member for the education functional constituency is critical of the EDB’s 2003 decision. “It was wasteful of us to leave the schools abandoned, especially primary schools,” Ip says. “I think the closing down scheme is worth challenging.”

Ip believes the reopening of vacant school premises in North District and Yuen Long would not only relieve the shortage of school places in the border districts in the short term, but also make extra classrooms available to make small-class teaching possible if student numbers drop again in the future.

Ip maintains the vacant schools should be used for educational purposes, as intended in the Town Planning Ordinance, which states that areas marked as “land for education” can only serve this one purpose.

The reality is very different. Of the 106 empty schools, only 45 premises have been re-allocated for school uses or other education purposes, whilst another 11 have been earmarked for further education uses. The EDB has informed the Planning Department that the remaining 50 are no longer suitable for educational use, as they are either too small or in remote locations.

These premises are then returned to the Lands Department or Housing Department for disposal. The Lands Department can then decide to rent out the premises to interested government departments or private organisations through short-term tenancies, usually of two to three years.

These former school premises have attracted a lot of interest. Man Chen-fai, vice-chairman of the Tai Po District Council, applied to transform Tai Hang Public School in Tai Po, which closed nine years ago, into a community centre that provides community services and features exhibits of Wen Tianxiang, a patriotic hero of the Southern Song Dynasty.