Buildings lie empty despite a shortage of school places in the northern New Territories

By Emily Chung and Natalie Tsoi

The roof has collapsed, the windows are shattered, trees and foliage have taken over. Except for the crumbling walls and doorframes, there is little to show there used to be a school here.

Tucked away in the village of Wai Tau in Tai Po, Lam Tsuen No. 3 Public School closed 30 years ago. It was one of the 66 schools shut down before 2003, a group that represents around a third of the 172 school premises in Hong Kong to be closed and abandoned to date.

The year 2003 is significant because that was when the Education Bureau (EDB) launched a scheme to close and consolidate what it called “high cost and under-utilised” primary schools in response to a decline in the birthrate in preceding years. The total school age population aged between six and 11 years was estimated to drop from more than 493,000 in 2002 to around 410,000 in 2010.

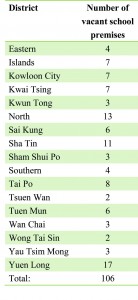

As result of the scheme, 106 schools have been shut since 2003, the majority of them in Yuen Long and North District. Meanwhile, 117 new school premises have been built to meet different demands in the same period.

Ironically, the districts hit hardest by school closures are those where school places are most in demand due to the growing number of cross-border students living in the Mainland but attending school in Hong Kong.

There were 3,500 cross-border students in all kindergartens, primary and secondary schools last year; that figure has risen to 16,300 this year. Meanwhile, the territory’s birthrate has continued to rise steadily since 2003.

Ip Kin-yuen, a Legislative Council member for the education functional constituency is critical of the EDB’s 2003 decision. “It was wasteful of us to leave the schools abandoned, especially primary schools,” Ip says. “I think the closing down scheme is worth challenging.”

Ip believes the reopening of vacant school premises in North District and Yuen Long would not only relieve the shortage of school places in the border districts in the short term, but also make extra classrooms available to make small-class teaching possible if student numbers drop again in the future.

Ip maintains the vacant schools should be used for educational purposes, as intended in the Town Planning Ordinance, which states that areas marked as “land for education” can only serve this one purpose.

The reality is very different. Of the 106 empty schools, only 45 premises have been re-allocated for school uses or other education purposes, whilst another 11 have been earmarked for further education uses. The EDB has informed the Planning Department that the remaining 50 are no longer suitable for educational use, as they are either too small or in remote locations.

These premises are then returned to the Lands Department or Housing Department for disposal. The Lands Department can then decide to rent out the premises to interested government departments or private organisations through short-term tenancies, usually of two to three years.

These former school premises have attracted a lot of interest. Man Chen-fai, vice-chairman of the Tai Po District Council, applied to transform Tai Hang Public School in Tai Po, which closed nine years ago, into a community centre that provides community services and features exhibits of Wen Tianxiang, a patriotic hero of the Southern Song Dynasty.

But Man says the red tape scuppered his plans. “The government asked us to go to the Planning Department to apply for the change of land use and to form an organising committee, like an NGO,” says Man, who has spent nearly eight years on the project. The cost of accountants and lawyers fees put Man off and he is now trying to apply for a short-term tenancy instead. He says the government guidelines seem arbitrary while the bureaucracy is inflexible.

As a result, few schools are rented out and most vacant school campuses are left to decay.

At the Lam Tsuen No. 3 Public School in Tai Po, nature has all but reclaimed the old school building. “It has been over a year since the government last came to cut the grass,” says Wong, the owner of a corner shop next to the abandoned school. “We villagers really want the government to cut down the weeds for us since there are snakes around.”

Wong says there had been talk of demolishing the ruins of the school and building an elderly home and community centre on the site. However, the talks ended in failure as there was opposition from some indigenous villagers who claimed ownership of the land.

Not all indigenous villagers are unwilling to set aside their claims to land on which schools have been abandoned. When Varsity visited the Kwu Tung Public Oi Wah School in Sheung Shui, a representative of Kwu Tung Village, Nam Siu-fu, was busy negotiating with a potential tenant interested in taking over the two-storey, 12 classroom school premises to operate a private school.

The school is just a 10-minute bus ride from Sheung Shui train station. And unlike most vacant school premises, it is still connected to electricity and water supplies. Since it closed in 2006, the building has been used regularly as a gathering place for villagers and as a polling station for Legislative and District Council elections. A few television series have also used it as a location set.

“We villagers will support whoever comes to occupy the school premises, as long as it can be of use, even if it means a private school organisation,” says Nam.

George Pang Chun-sing, a professional civil and structural engineer and district councillor, agrees with Nam. Pang points out that many vacant school premises in North District are structurally sound and safe to be reused as schools. Pang says that while many village schools are dated and cannot be compared to the modern state-of-art school complexes built after 2000, they can still provide a quick solution to ease the demand for school places.

Pang is critical of the government’s inability to pay heed to the public’s needs. He says that even if the vacant school premises are inappropriate for education purposes, the sites can still be refitted to become elderly homes and town halls which are sorely lacking in North District.

Pang says proposals to those ends are repeatedly rejected by the Lands Department because they would require a change in land use under the Town Planning Ordinance. Yet, he points out permission was granted to turn a site opposite the vacant Kin Tak Primary School on Fan Kam Road from one earmarked for government, institution or community use, into luxurious properties.

“We are all aware of the serious shortage for primary one school places. We have schools and premises readily available; why is the government still reluctant to reopen the schools?” says Pang.

“Instead, the government changed the land use in order to sell sites to property developers. We are all very dissatisfied with this deal. You can see the government departments and Education Bureau are not really trying to help the cross-border and cross-district students.”

Pang suspects the reason the government is unwilling to reopen the schools or allow them to be used for other community purposes, is because it foresees a drop in demand for primary one places in 2018 due to the restrictions on mainland mothers giving birth in Hong Kong.

Ma Siu-leung, chief executive of the Fung Kai Public School is also critical of what he calls the government’s double standards. After the Fung Kai No. 2 Secondary School closed in 2006, Ma submitted a detailed proposal to the EDB to turn the vacant premises into a small, international boarding school. Ma says the EDB dragged its feet and asked what he believes were unreasonable and obstructive questions.

“When I discussed my plan with the government, they said that there was no boarding school policy and international school policy in Hong Kong,” says Ma. The application was finally approved two years later, in 2008, but by that time Ma learned that the elite British Harrow School was going to open an international school in Hong Kong. Ma decided the development meant his project was no longer viable.

“I discovered I was never given a shot, as I stood in the way of another deal the bureau was making with Harrow School,” he says. To date, the EDB has not replied to Varsity’s requests for a response to the charge.

As legal attempts to use vacant premises usually fail, some people have taken the matter in their own hands and are using the premises without official permission.

Urban Fragment is a group of photographers who like shooting in abandoned places, including school premises. Photographer Cheung Man-kit has taken photographs in more than 10 abandoned schools. He often found signs that people had been sleeping in them. In some schools, walls are covered with graffiti.

Sampson Wong Yu-hin, one of the founders of Emptyscape, a group that promotes art in abandoned areas, shares similar experiences. “Many people use the schools without official permission. TVB was here some time ago while some people use it for dog training. No one cares if you just walk in,” says Wong.

In June, Emptyscape organised the Ping Che Village School Art Festival in the school of the same name which closed in 2006. Although the event was sponsored by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council, the use of the primary school campus was not officially authorised by the government. A villager helped organisers open the gate to the school.

Wong says the control of a lot of village schools in the New Territories is held by the Rural Committees or village heads. Even when an organisation has permission from the government to use a school, they still have to get these residents’ approval as they have the keys to the schools.

Now the hustle and bustle of the art festival has long ceased, Wong wants the school to be a school again.

“What a pity…many places in Hong Kong are abandoned,” says Wong. “It would be perfect if it can become a functioning school again. It does not have to be a regular secondary or primary school. An art school would also be great.”

Edited by Thee Lui