Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

Swordsmen of the Screen

Cinematic Exchanges between Hong Kong and Japan

The Japanese film industry reached its zenith with a total 1.12 billion cinemagoers in 1958, equivalent to every Japanese citizen going to the cinema 11 times that year. However, the figure more than halved in 1967, by which time the Shaw Brothers had entered its golden era. ‘Ever since Shaw Brothers launched the new-style swordplay films, Japanese samurai films’ leading role in Asian cinemas was eventually displaced,’ says Prof. Kinnia Yau of CUHK’s Department of Japanese Studies.

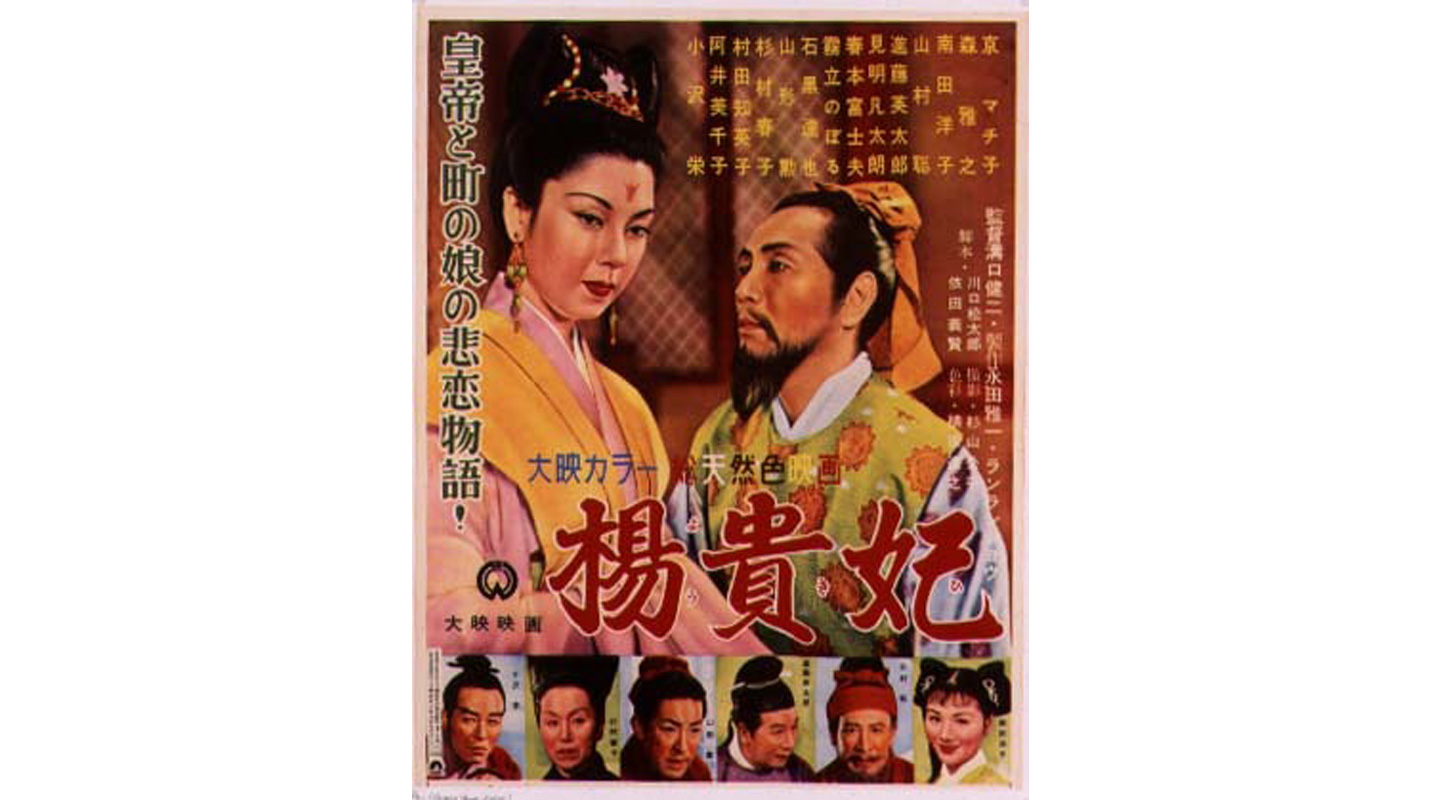

The post-WWII politico-economic order led to many cinematic collaborations between Japan and Hong Kong. The first of its kind, The Princess Yang Kwei Fei, was directed by Kenji Mizoguchi and was co-produced by Masaichi Nagata and Run Run Shaw. In 1953, Nagata and Shaw took the lead to found the Southeast Asian Motion Picture Producers’ Association, which organized the annual Southeast Asian Film Festival. By working with the Japanese, Run Run Shaw had intended to import cinematographic techniques to improve the quality and quantity of Shaw Brothers’ productions. In addition to employing some Japanese cameramen such as Nishimoto Tadashi, he also brought in the Eastmancolor motion-picture technology, widescreen film, and new genres like the new-style swordplay films. These innovative attempts eventually opened up a young market.

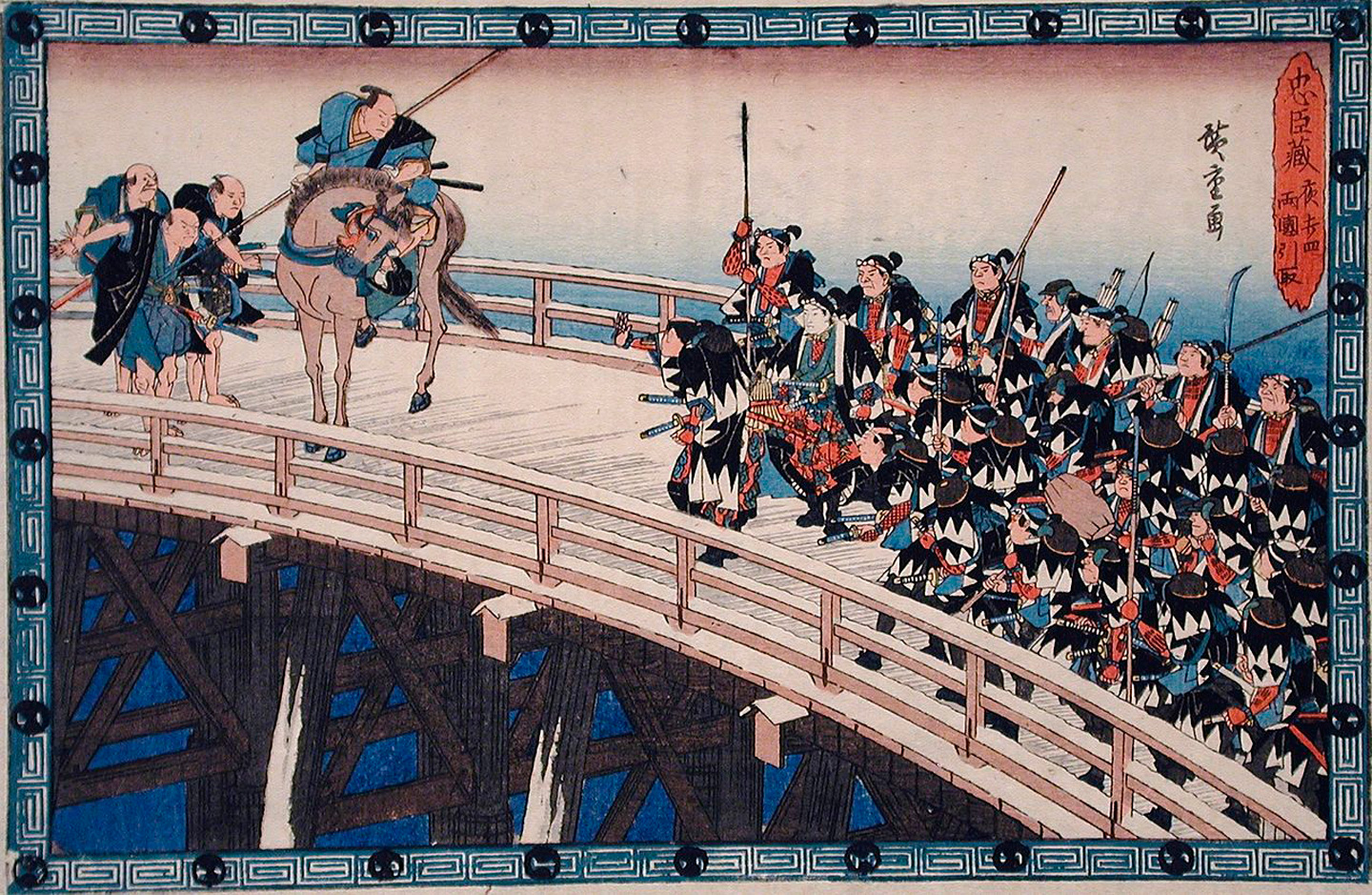

Action films flourished in the European, US and Japanese cinemas in the 60s, with Hollywood’s ‘James Bond’ series, Italian ‘Spaghetti Westerns’, and Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sanjuro. The slow-paced, black-and-white characterization, visibly feigned duels in the traditional swordplay films could no longer appeal to the Hong Kong audiences. Film researcher Yu Mo-wan revealed that Run Run Shaw bought his directors more than 200 samurai films from which to learn cinematographic techniques. Characteristics of the samurai films could be found in King Hu’s Come Drink with Me and Chang Cheh’s The One-Armed Swordsman, with a high concentration of sensory stimuli, faster motion and authenticity. ‘In the fighting scenes of Kurosawa’s films, Toshiro Mifune beats his enemies in the blink of an eye. In contrast, the protagonists in the traditional swordplay films spoke a lot while fighting and dragged down the story.’

Before the advent of the new-style swordplay films, female leading roles dominated the Hong Kong cinema. In the then popular huangmei opera genre, the male roles were even played by actresses. Chang Cheh injected masculine heroism into The One-Armed Swordsman, setting an example for the new-style swordplay films. His film hit the big time, which grossed over HK$1 million, a new box-office record at the time. Hong Kong cinema became more masculine thereafter. ‘The influence of samurai films could still be felt in contemporary swordplay films. Ann Hui admitted that The Romance of Book and Sword she directed was partly inspired by Seven Samurai and The Shogun's Samurai.’

Professor Yau opines that only the form of samurai films was adopted in the new-style swordplay films, whose essence was still the Chinese wuxia spirit. Japanese directors had directed films in the musical, crime, mystery and romance genres, but not the new-style swordplay films. ‘Obviously Run Run Shaw only wanted the western techniques that came with the Japanese directors.’ Bushido shares a lot in common with the Chinese wuxia spirit, both of which embrace righteous self-sacrifice. The former was gradually distorted, however, and became identified with a blind loyalty to royalty. The samurais were still fearless of death, but the pursuit of righteousness was neglected. In fact, many post-war bushido films reflected the conscientiousness and nakama (camaraderie among peers) of the samurai culture, instead of blind loyalty or glorified death. ‘The Japanese are fond of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms because of its nakama elements. The heroic romance and nakama portrayed in John Woo’s action film A Better Tomorrow also appealed to Japanese audiences.’

‘Studying cinematic exchanges between Hong Kong and Japan not only deepens our understanding of Sino–Japanese relations and Hong Kong history, but also touches on larger economic, political and gender issues,’ Professor Yau says, ‘Films are not merely art or entertainment.’ In the romance film Shina No Yoru (1940), the actress Li Hsiang-lan (aka Yoshiko Yamaguchi) played a shy and fragile Chinese woman who fell in love with a Japanese man. The unequal gender relationship embodying men’s superiority reflected Japanese superiority in the political, economic and cultural spheres. In the 60s, this was still common in some Japan–Hong Kong or Japan–Taiwan co-productions. A Night in Hong Kong starring Akira Takarada and Yu Min was an example. It was until the early 90s when Japan entered a prolonged economic slump that more Japanese actresses played the supporting female roles, for example, in the Japan–South Korea co-produced Virgin Snow (2007).

J. Lau

This article was originally published in No. 518, Newsletter in May 2018.