Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

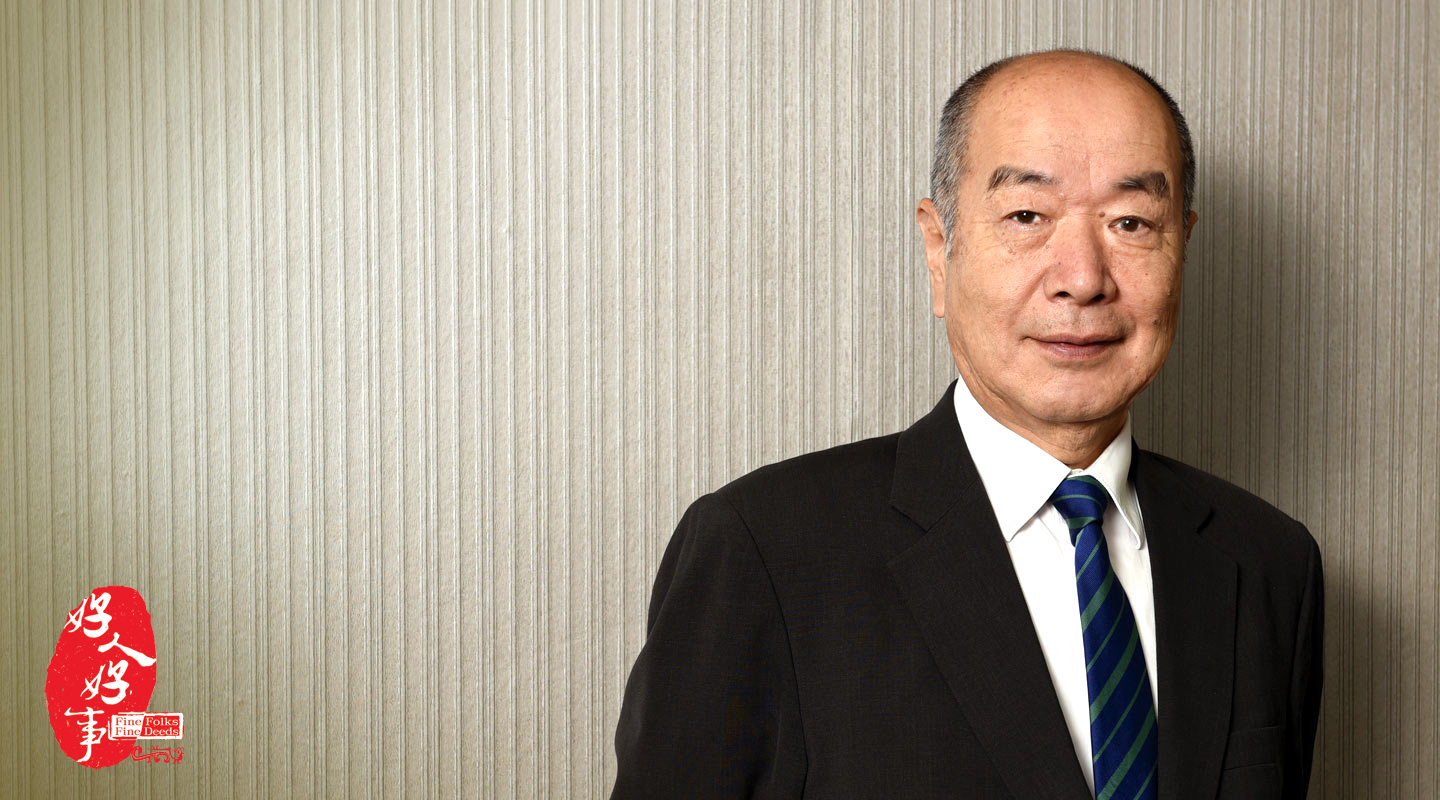

At Home in His Second Home

Alex Yasumoto turns culture shock into philanthropy

Dr. Alex K. Yasumoto gained his first international experience in Hong Kong in 1986, at the age of 40, when he began to explore places to diversify his family’s business investment. At that time, he spoke very little English though he had learnt the language in Japan since junior high school.

Limited English, Unlimited Aspirations

‘Everything’s new to me. The property market operated differently from that of Japan. My English was terrible and that posed a great challenge to me. I found it very hard to communicate,’ he recalled. Every night when he got back to the hotel, he read the business documents and looked up every word in the dictionary. It often took him more than an hour to finish a page.

Poor English had not deterred him from starting his business overseas. In the end, he saved the family business when Japan’s bubble economy burst in the 1980s. Looking back, he attributed the right move to his positive thinking, ‘I faced the challenge and sought solutions for the problem instead of backing off.’

Broadening Exposure, Broadening Mind

Having learned more about the foreign places, including Australia, Hong Kong and Cambodia, Dr. Yasumoto found that there were many barriers other than language. ‘The measurement systems are different. At the beginning I was always doing conversions in terms of area, currencies, etc., in my mind, evaluating everything by reference to Japan. But later I found that one should only make comparisons within the local context.’

Dr. Yasumoto has come to see that in other cultures people take different approaches to business and to life, one example being the concept of contract. In his recently published Yasumoto’s Passage to International Business, he notes that businessmen in the West would engage in numerous rounds of negotiation to hammer out every detail or eventuality to be provided for in the contract. Nothing could be changed after the contract is entered into. In the East, e.g., Japan, business collaboration is established on the basis of mutual trust. Contracts are drafted as broad framework for reference only, and any dispute arising afterwards will be settled through reconciliation.

Hong Kong, as he observed, was a place which upheld the spirit of contract in the western practice when he set foot in the colony in 1986, shortly after the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration. There were diverse views about the economic future of Hong Kong then. Dr. Yasumoto was on the optimistic side. He foresaw that the property market would go up, which really did. He settled in Hong Kong and has made it one of his major business bases until now.

To him, Hong Kong remains the best place for business. ‘Even though many people are losing confidence in Hong Kong, I still see a lot of opportunities. Compared to other popular Asian countries for foreign investment, such as Vietnam and the Philippines, the commercial, economic and legal systems here are much more established and healthy. The efficiency here is also beyond compare. People are money-conscious and quick in decision-making.’

Reap and Give

Dr. Yasumoto’s real estate business prospered in Hong Kong. In the mid-2000s, he sold a building of low occupancy rate which he had held for three years. Though he made a profit of HK$100 million, the Inland Revenue did not consider the buying and selling a speculative activity and granted him tax exemption. In gratitude, he decided to pay back to Hong Kong by donating to a public organization.

‘Prof. Lawrence J. Lau, then Vice-Chancellor of CUHK, and the senior management presented a few attractive proposals, including the establishment of an endowment fund and scholarship schemes for promoting international exchange activities. I found at CUHK an international ethos and aspirations that matched my own educational ideals, so I decided to donate the HK$100 million to CUHK.’ Through the University Grants Committee’s Matching Grant Scheme, this magnanimous donation in 2005 was able to secure another HK$50 million for CUHK, serving as a strong booster for the University’s development.

Knowing Others, Knowing Oneself

Dr. Yasumoto sees internationalization as the keystone of education. He believes that immersion into another culture can broaden one’s vision and enhance self-reflection. His book, originally written in Japanese with an aim to enlighten young people in his home country, contains objective comparisons between Japan and other parts of the world in terms of business practice, religion, customs, education and philanthropic culture.

‘After I went abroad for business, my thinking was no longer confined to the traditional Japanese way. By knowing another culture more deeply, one can look at things from an alternative angle. Internationalization provides the stepping stones to understanding different cultures. It means not just understanding others but also accepting others, and also understanding oneself.’ As such, Dr. Yasumoto is keen to provide students with opportunities of the kind he did not have himself until the age of 40.

The Yasumoto International Exchange Scholarship Scheme inaugurated in 2007 became the largest scheme of its kind and has since benefited more than 4,000 CUHK students to study for up to a year at prestigious universities in more than 30 countries and regions around the world. The Yasumoto International Academic Park, named after him and completed in 2012, serves on the CUHK campus as a forum where international and local students congregate, bond and share their aspirations and world vision.

Less for More

The Centre for Sign Linguistics and Deaf Studies at CUHK is another major beneficiary of Dr. Yasumoto’s kindness. A scholarship for sign language interpretation training was also established under his name. A critic of micromanagement, he trusts the University to allocate funds from his donation as it deems appropriate. In running his business, he believes in creating a positive corporate environment in which employees are given freedom and scope to realize the goals of the business in their own ways. ‘I let the directors and managers do their jobs. I have nothing to do,’ he joked. Doing nothing to do more—could this philosophy of Laozi’s be one of Dr. Yasumoto’s gains from his cross-cultural experience?

By Sandra Lo, ISO

This article was originally published in No. 491, Newsletter in Jan 2017.