Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

Emperor’s Tongue

An F&B view of administrative law in Tang China

To earthlings and commoners like us, the dining table for the royalty is a smorgasbord of precious foodstuffs and exquisite flavours. To the legal historian, however, what’s on the plate and how a regal meal is served provide insights into how the government is structured and run.

Owing to its immense success and popularity in the preceding years, the Faculty of Law of CUHK is presenting the latest, the sixth, instalment of the Greater China Legal History Seminar Series to continue the exchanges on the historical development of various legal issues of interest in the Greater China region.

Prof. Norman P. Ho, Professor of Law at the Peking University School of Transnational Law, needs no introduction to the fans of the series. He spoke on Confucianism and Chinese law in the 2018–19 season, and on mutilating corporal punishments in ancient China in the next. During the lunch hours on 18 September, he kicked off the 2020–21 season by delivering via Zoom a sumptuous talk titled ‘Feeding the Emperor – Administrative Law in Tang Dynasty China’.

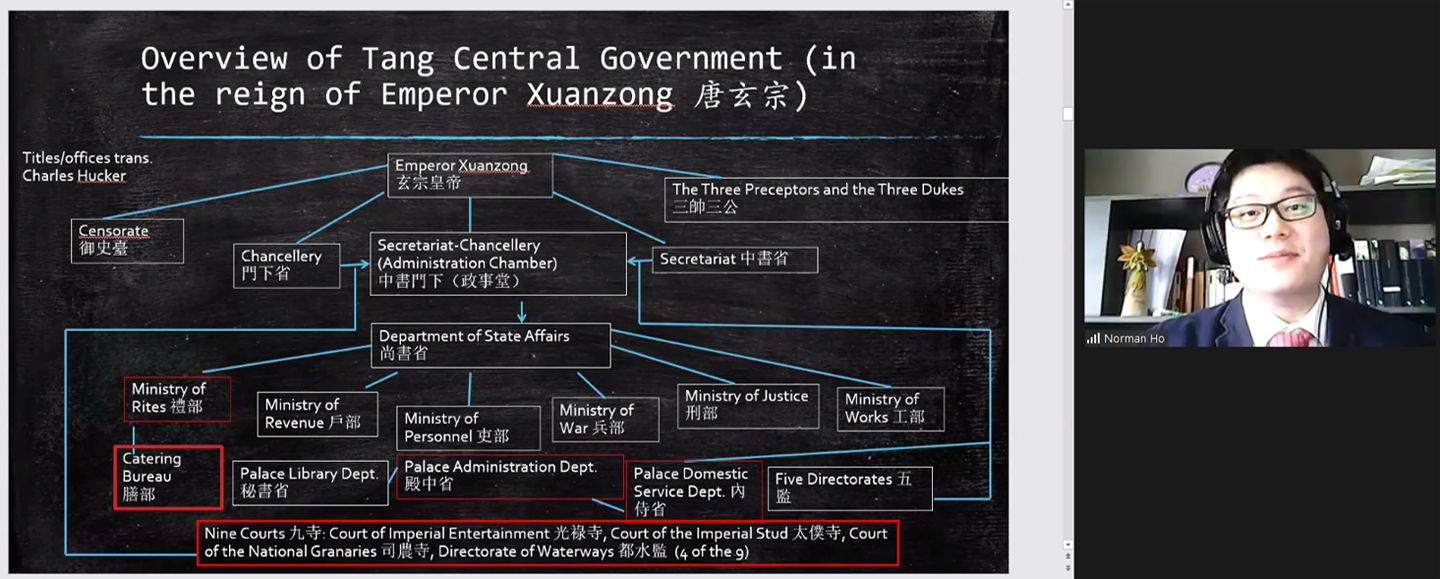

He began his talk by focusing on the Tang Liu Dian (TLD), the earliest surviving collection of Chinese administrative law that dates back to the eighth century at the apex of the Tang Dynasty under the reign of Emperor Xuanzong (reigned 713–756).

The TLD is an invaluable document for understanding the Tang administration. Its purview includes all the institutions in the central Tang government, their relative positions within the administrative hierarchy, their division of labour, down to the ranks and numbers of personnel employed. Judging from the sheer size and importance occupied by this food bureaucracy, the emperor and his royal household had a large appetite indeed. By Professor Ho’s reckoning, a total of 5,656 members of staff were involved in the food bureaucracy, accounting for 50% of the total staff in all institutions recorded in the TLD.

To give an example, the Court of the National Granaries was tasked with provisioning the green vegetables in the emperor’s diet. The Court, which was further subdivided into a number of specialized offices and directorates (there was even a directorate of bamboo, bamboo being a highly regarded plant and food in Tang), employed 562 members of staff, with titles ranging from minister, vice-minister, aid-to-the-minister, recorder, overseer, repositor, scribe, accounts clerk, managing clerk and clerk, each with specified rank and number.

The food bureaucracy structure in the TLD covers the sourcing, preparing and serving of meat, vegetables, seafood and beverages including wines for the emperor and his household. The purposes are not only limited to their personal enjoyment, however, but also for other imperial occasions and state ceremonies.

Professor Ho then went from the TLD to the penal code of the Tang Dynasty contained in Tang Lü. He pointed out that the entire food bureaucracy structure was buttressed by strict penal provisions that govern the food personnel (covering many more functions than that of cooks) in the TLD.

For example, Article 103 of Tang Lü specifies in no ambiguous terms that any member of staff who violates the dietary provisions in preparing food for the emperor commits an offence. Violation by error is punishable by strangulation. If the food or drink is found unclean, the responsible members of staff gets two years in penal servitude. If any ingredient is impure or chosen out of season (some foods are taboos for particular seasons), he gets one year. If a taster neglects his duty to pre-taste any dish to be offered to the emperor, he gets 100 blows with a heavy stick.

Why this mammoth and intricate machinery in the matter of royal F&B? Professor Ho suggested that it might be all for protecting, strengthening and enhancing the prestige and power of the emperor, his image and office.

Professor Ho’s presentation was spiced up throughout with revealing references and savoury anecdotes. To get a first taste or second helping of the seminar, you can watch its video here.

By tommycho@cuhkcontents