Another obstacle to the work of Hong Kong NGOs in China is the Chinese government’s ever-changing attitude towards them. In 2012, the registration process for NGOs was simplified in cities like Beijing and Guangzhou, but the easing of rules governing registration may just be giving the illusion that the government is loosening its control. Some believe registration actually creates difficulties for NGOs because they are then forbidden from receiving foreign funding after registration.

“Our work in the Mainland is like going back and forth between different government departments and enterprises, striving to push the boundary and making our work more effective,” Fung says.

Despite all the challenges, many still see hope for the future of China’s civil society. Wang Yong, project coordinator of the Centre for Civil Society Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, is delighted to see the rise of civic awareness in mainland China. She predicts that despite twists and turns along the way, the level of development of civil society in China will continue to grow in the long run.

Howard Liu Hung-to, China programme director of Oxfam Hong Kong, is also optimistic about the future of Hong Kong NGOs in China. “Hong Kong [NGOs] should not be afraid of the Chinese government and think of it as a monolithic block,” he says. “Many policies require cooperation with the Chinese government and, although progress is slow, Hong Kong [NGOs] can influence them.”

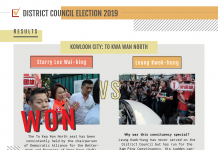

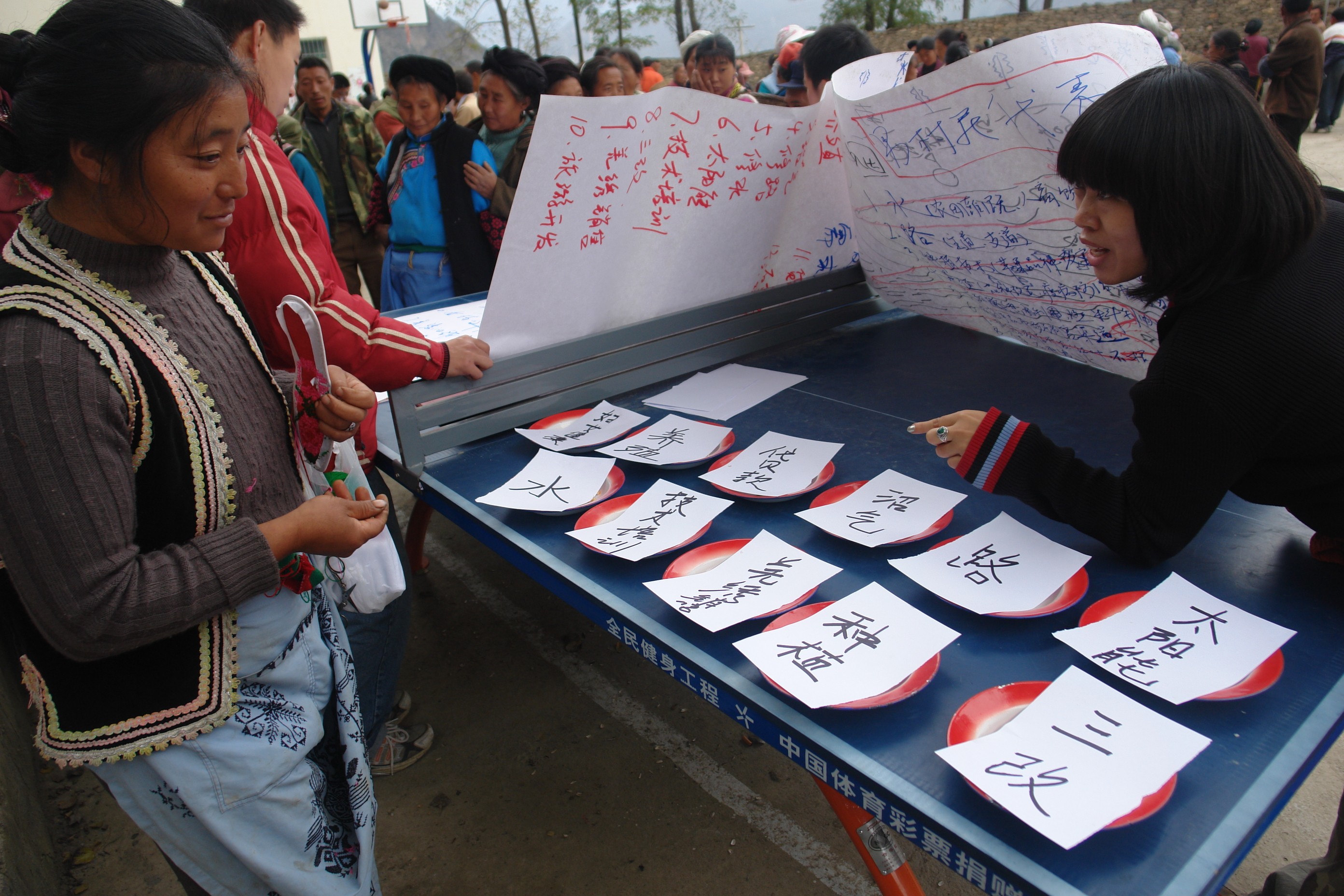

Liu hopes that eventually the interaction between civil societies in Hong Kong and mainland China will not be so one-sided: while Hong Kong shares its experiences with China, it can also learn from good cases in China, he says. He illustrates this with the example of Shengli Village, a remote village in Sichuan Province which was flattened by the 2008 earthquake. In 2009, the villagers were able to decide on democratic issues of their village through voting. They planned the allocation of resources and budgeting, and monitored the reconstruction of the 3.6 km access road to their community.

“If such a remote village in the Mainland can do that [democracy], Hong Kong should also have more space and confidence to do so,” Liu says.

Edited by Frances Sit