Hong Kong protesters turn to social media to organise and mobilise themselves

By Lambert Siu

Telegram on the front line

Davis, a fourth-year university student, who declines to reveal his full name, participates as a frontline protester in the anti-extradition bill protests, which have gripped the city for months. Like many other Hong Kong young people, the 21-year-old takes to the streets to demand political self-determination and autonomy of this city.

Different from conventional social movements, this pro-democracy campaign sparked by a controversial and now-abandoned bill is leaderless, faceless and nameless. Without veteran political leaders directing courses of action, this time, Hong Kong protesters adopt a citizen self-mobilisation approach: they turn to social media platforms to organise themselves.

“We acquire information from Telegram and discuss our next steps at the scene accordingly,” Davis says, describing how he communicates and makes decisions collectively with other frontline protesters. He says they freely share their opinions on the spot and those who are more familiar with the area they are in will point out some secret escape routes only residents of that particular district know.

Telegram is an encrypted messaging app which allows users to create public channels to share information. Users can also create smaller private chat groups to have conversations without displaying their telephone numbers or identities so that they can be protected from potential monitoring by authorities. This app has become one of the most downloaded apps in the city amid the ongoing protests, according to mobile data provider Sensor Tower.

Some public channels which provide instant information on the movement, have up to more than 200,000 subscribers, representing over 2 per cent of Hong Kong’s entire population. The information usually comes from news reports and citizens who call themselves “sentries”, tipping off the channels first-hand updates about locations of police and traffic situations. The immediate access to information facilitates protesters’ wildcat and guerrilla-like actions, which invokes the Bruce Lee-inspired “Be Water” philosophy.

Davis says sometimes frontline protesters quarrel with each other because of their different views on what to do next. “But if someone starts taking action, we will end our arguments,” he says. “We don’t reproach other protesters as we stick to the principle of ‘not splitting up’.”

The Hong Kong protesters have demonstrated strong solidarity by minimising any possible negative impact on the movement and it is illustrated by how they treat misinformation circulating online. Davis says protesters rarely vote on Telegram to decide their next moves during protests because they worry about making wrong decisions if they rely too much on the unverified news spreading on social media. Instead, they tend to judge by their own observations at protest sites.

Davis was once misled by a Telegram message saying that legions of riot police had arrived at the scene. But the fact was that there were only one or two police cars. “Sometimes it is very hard to verify authenticity of information, but it’s not a big problem,” says Davis. “If there is something really serious happening, the whole world would know that. Mistakes only exist in some petty things.”

Virtual Command Centres: LIHKG and Telegram

According to an onsite survey conducted by the Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), 41.8 per cent of the respondents who took part in the march organised by Civil Human Rights Front on August 18 always used Telegram to acquire information related to the protests, while 57.3 per cent of those surveyed always obtained information from another online platform LIHKG. Dubbed “Hong Kong Reddit”, this online forum is crowned as one of the virtual command centres of the decentralised movement, in which protesters discuss protest tactics and organise protest activities.

The onsite survey found that these social media sites are embraced not just by the youth but also by the older generation, who are often regarded as technology laggards. More than a third of the respondents aged 50 and above said that they always used LIHKG to acquire information.

Florence, a middle-aged housewife who refuses to disclose her full name, first learned about the two messaging apps from young protesters in the June 12 demonstration, during which thousands gathered around the Legislative Council Complex as an attempt to stop the extradition bill’s second reading. “When I saw the frontline protesters building mills barriers, I wanted to know what their next moves were. That was why I downloaded these apps,” she says.

Florence is not a newcomer to social movements. She joined marches in the city whenever huge issues arose, including the demonstration in support of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, the anti-Article 23 protest in 2003 and the Umbrella Movement in 2014. But she was never a core player in any of these movements.

“This time it’s different. It is a leaderless movement. Everyone can start up something,” Florence says.

She initiated a HK$10 million “Sue the Abuser” crowdfunding campaign together with her friends to help victims sue police officers over their alleged mistreatment. They talk in small groups on Telegram, coordinating logistics and publicity of the project.

As a beginner at Telegram and LIHKG, Florence says learning how to use these applications is not difficult for her because their design is simple. “The first thing I do after waking up is to check Telegram on my phone,” she says. She reads Telegram messages as daily news because the public channels will sum up what happened the night before.

As for LIHKG, this app allows its community members to vote up and down on all the threads, making the most popular posts appear on the forum’s front page. Florence says the function helps her save time by screening out useless topics.

Set up in late 2016, this online forum was once widely used by university students where they discussed everything from gaming to dating. After the large-scale anti-government movement broke out, this forum has become a major discussion space for protesters to campaign protest ideas and strategies, in which freedom of speech is emphasised and the practice of anonymity gives users a sense of security.

Florence often browses LIHKG to check out details of protest activities. She says social media enables her to learn more information about the movement.

From online to offline

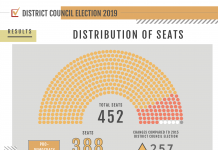

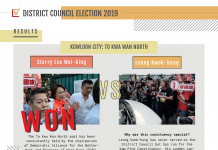

Some other LIHKG users are thinking about how to transform an online brainwave into offline political energy in the communities. Yoyo is one of the convenors of Hi! Freedom, a platform providing assistance and support for political amateurs who will run in the upcoming District Council elections as first-time candidates. Along with some of his friends, he wrote a post on LIHKG this June, appealing to netizens to stand for the November election and replace pro-establishment district councillors who were elected uncontested four years ago.

“I was once in despair about Hong Kong society, but this time I see hope in the movement,” says Yoyo.

After millions of people flooded the streets on June 16, mounting resistance to the Chief Executive’s governance, an idea popped up into Yoyo’s mind: “There are two million people on the streets. Can we bring their power to the district councils?” Four days later, he posted the first post on LIHKG and recruited the first squad of volunteers via the online forum.

Yoyo and his teammates actually employ multiple social media networks. After absorbing new blood into the team, they created several smaller chat groups on Telegram based on constituencies and work categories. They also opened a Facebook page for Hi! Freedom earning around 6,700 likes.

Features of decentralised leadership

Professor Francis Lee Lap-fung, school director of CUHK’s School of Journalism and Communication, thinks the widespread popularity of these two online platforms during the months-long social movement is rooted in their “self-enforcement dynamics”, which means that the more users the platforms attract, the greater value they have. Functioning as a cycle, when these platforms play an increasingly important role in mobilising protesters, more and more people will turn to them in return.

He says this online-driven and leaderless organisation model can generate public enthusiasm to get involved in the movement. “All the people think of is how they can contribute to the movement in their own way, which opens up more possibilities for innovations in protest tactics,” Lee says. “A stronger sense of engagement also helps sustain the participants’ support for the movement,” he adds.

On October 31, the High Court of Hong Kong issued an interim injunction to bar the public from publishing any messages online that encourages or incites violence that could do harm to individuals or cause damage to their property. This temporary injunction remains in force until November 15 when a formal hearing is held. The ban applicable to any online platforms specifically cites LIHKG and Telegram as examples at the request of the Department of Justice.

Edited by Gloria Li