Independent filmmakers are the new standard-bearers for Hong Kong cinema

By Edith Chung & Johanna Chan

When the dystopian independent movie Ten Years defied expectations to win Best Film at the 2016 Hong Kong Film Awards, its producer Andrew Choi took to the podium and said the award showed there were a lot of possibilities for Hong Kong films.

At the same awards ceremony a year later, another local film, Trivisa, produced by Johnnie To Kei-fung as a vehicle to nurture young directors, became the night’s biggest winner. It won five awards, including Best Film and Best Director. The Best New Director’s award that night went to the young director of another low-budget local film, Mad World.

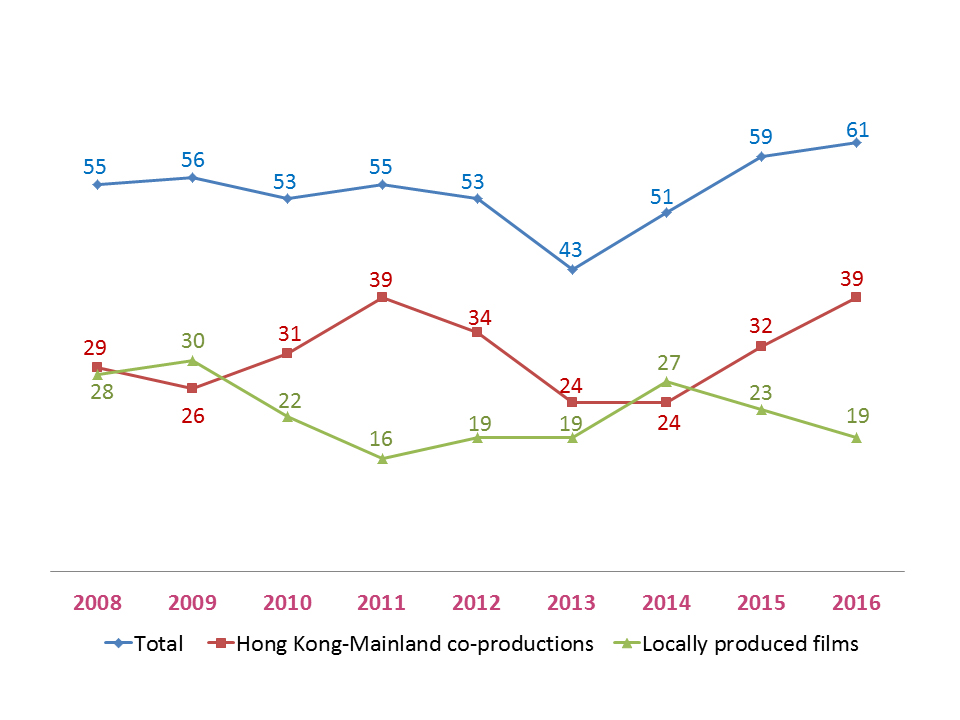

Despite these accolades, the environment is tough for Hong Kong films. The number of local films, excluding those co-produced with mainland film companies, dropped from 28 in 2008 to just 19 in 2016.

Source: Hong Kong Film Development Council, CreateHK

With the once mighty Hong Kong film industry in slow decline since the 1990s, more and more filmmakers have turned to the mainland market and co-productions with mainland film companies. The number of co-productions increased from 29 in 2008 to 39 in 2016. Co-productions generally make more at the box office, taking in around eight times as much as locally produced films in 2016.

However, even taking into account Hong Kong-Mainland co-productions, there are still far fewer Hong Kong films being made now than during the industry’s heyday. In 2015, there were 59 local films, including Mainland-Hong Kong co-productions, which is 60 per cent less than the number of Hong Kong films produced 20 years ago.

Still, the numbers may not tell the whole story. With a slew of young local filmmakers intent on telling Hong Kong stories and turning to alternative forms of distribution, some are pointing to the start of a revival of Hong Kong film, albeit on a smaller scale.

Ng Ka-leung is one of the producers and directors of Ten Years. The 37-year-old thinks this generation of filmmakers may see success differently to their seniors.

“Their aspirations, their courage to express themselves is much stronger than the industry personnel of the past, they don’t carry the same baggage,” says Ng.

For these young filmmakers, movies are no longer just a form of entertainment. Instead, Ng says some young filmmakers want their works to provoke audiences to reflect upon society. He sees an increasing number of films addressing social issues, which can lead to a change in audiences’ attitudes towards and expectations of films.

Taking Ten Years as an example, Ng says it would have received a very different reaction if it was released 10 years ago. It became a phenomenon through the combination of its filmmakers, the audience and the general social atmosphere, he explains.

However, strong public interest and acclaim in Ten Years did not secure the film’s screening in mainstream cinemas. Ng says this shows there is an “absolute breakdown” in the distribution system and that self-censorship and political pressures are rife in the commercial film business.

Photo courtesy of Ng Ka-leung

Ng and his colleagues got around the restrictions by organising screenings and post-screening discussion sessions in the community. On April 1 2016, they worked with educational institutions and community groups to hold a simultaneous screening at 34 different public locations in Hong Kong. Although guerilla screenings in community halls, schools and other public spaces is an alternative, Ng says there has to be a new mindset and willingness to take risks if there is really to be an industry revival.

Chan Tze-woon, a 30-year-old independent film director, is optimistic that independent films can spearhead a revival in Hong Kong film. Chan spent around half a year working in the commercial film industry after graduating from university – as a script supervisor, a director’s assistant and on post-production. But he found working in the commercial sector too constricting and decided to step out on his own to seek more creative freedom.

Using his own savings and with support from a backer, Chan made the low-budget 2016 feature Yellowing in 2016, a documentary about the 2014 Umbrella Movement. It cost just HK$ 50,000 to make but was nominated for a Golden Horse Award for Best Documentary and was screened at film festivals in Taiwan and Vancouver. Despite gaining international recognition, the film was screened in only one local mainstream cinema. Chan says it is hard to say whether this was entirely due to political reasons as mainstream cinemas in Hong Kong do not tend to screen documentaries but he is worried about increased self-censorship, especially after Ten Years.

Photo courtesy of Chan Tze-woon

Being an independent filmmaker is tough, but one reason for Chan’s optimism is that he sees there are other young directors facing up to the same challenges. “There are always possibilities, so you can never say one chooses a path that nobody takes,” he says.

At the same time, it is hard for full-time independent directors to sustain a living in Hong Kong, so many of them, including Chan, take freelance jobs. In order to make ends meet, Wong Wai-nap, who makes independent short films, also teaches creative media at the HKICC Shau Kee School of Creativity. After graduating in creative media at City University, Wong had high hopes of working in the commercial film industry.

But the stress of paying off his student loans and the long irregular hours with low pay forced him to quit and work for a production house instead. Like Chan, Wong thinks there are too many restrictive factors in the commercial film industry, and these cannot be changed. Independent films allow filmmakers to produce the works they want to create.

Wong says the emergence of alternative screening methods provides different channels for films to reach a wider range of audiences. Apart from community screenings, he thinks it is good to show works at overseas film festivals as films should never be restricted to the local community.

Vincent Chui Wan-shun is an independent film producer and one of the founders of Ying E Chi, a non-profit organisation that organises the Hong Kong Independent Film Festival. Although he agrees that it is difficult to screen independent films in mainstream cinemas, he maintains that official screening opportunities are important to motivate new directors, and are a recognition of their work.

Chui adds that while the domestic market in Hong Kong is too small to support large-scale productions, it is still possible to produce films that Hong Kong people are interested in watching with low budgets. “Don’t imagine and expect too much. Just focus on what you’re doing right now,” is his advice for young filmmakers. But to really revive the industry, he says there must be more nurturing of new talent and greater allocation of resources to new directors.

In an attempt to revive the film industry, the government set up the Film Development Fund (FDF) to subsidise local film productions and has injected HK$540 million into the fund since 2005. It launched the First Feature Film Initiative (FFFI) in 2013, with funds from the FDF. The funds are to support new local film directors and their production teams to make their first feature films on a commercial basis. Mad World, the fifth highest grossing local film in 2017 with HK$16 million, is one of the five films financed under the fund so far. Others include the acclaimed Weeds on Fire (2016) and Somewhere Beyond the Mist (2017).

While Chui regards the scheme as a good career starter for young directors, Shu Kei says neither the FDF nor the government is helping young directors and the industry at all. Shu is the former dean of the School of Film and Television at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts and the vice-chairman of Freshwave, a short film competition and screening platform for young film talent. Taking the production of Mad World as an example, he says anyone familiar with the film industry knows that a HK$2 million subsidy is insufficient for a HK$10 million production, and he describes the FFFI’s amount of subsidy for the film as “ridiculous”.

“It’s an illusion. the success of the films has nothing to do with the First Feature Film Initiative,” says Shu.

He says the government’s role has always been vague since it is unfamiliar with the film industry and the challenges it faces. He says the small amount of funding not only affects the quality of filming equipment, the scale and quality of the cast and crew but also the audiences a film will attract. Shu explains most audiences prefer large-scale, big-budget productions to low budget ones.

Some attribute young directors’ failure to break through in the film industry to inadequate film education and nurturing, but Shu believes the issue lies beyond education. He says that while the academy can provide a foundation and a basic set of skills for students, it should not be regarded as a vocational school and graduates are merely beginners. They only undergo training for the production of shorts and lack hands-on experience on commercial productions. Shu thinks young directors must be motivated to search for learning opportunities.

Film critic Shum Long-tin agrees the government’s policies do not adequately address Hong Kong’s current situation. He says there is a need to modify current arrangements as filmmakers have complained about the complicated, bureaucratic procedures involved in applying for funding. Shum says applicants do not really know how the FDF panel assesses applications and there is a lack of youth participation in the process.

“The government is neither letting nor trusting young people to be part of the board,” Shum says. “Youth participation must be present in the discussion of film policies and government subsidy.”

Overall, Shum believes there is a Hong Kong film revival of sorts, with an increasing number of young filmmakers making films with a strong local ethos and characteristics. But he believes the revival would be more successful with a rethink in the way resources are allocated and the replacement of decision-makers in the process.

“The industry’s revival really depends on whether the government’s willing to make changes and come up with a comprehensive film policy,” he says.

Edited by Selena Chan