How Cells Cheat Death

June 2012

A major treatment for many cancers, chemotherapy can cause cancer cells into apoptosis, a cell-dying process. But it is very common that patients would experience cancer recurrences after chemotherapy and mortality is very high when cancers return. A study from CUHK in 2009 showed that cancer cells could evade the apoptotic dying process even after passing the presumed point of no return, and this may be one of the causes of cancer recurrences. Now a new study from the same research team demonstrates that like cancer cells, normal cells can also evade apoptosis.

The study, appearing as a highlighted article in the 15 June issue of the Molecular Biology of the Cell, found that both normal cells and cancer cells can reverse chemical-induced apoptosis. And cancer cells become more aggressive while normal cells may turn cancerous after they have reversed the dying process and survived.

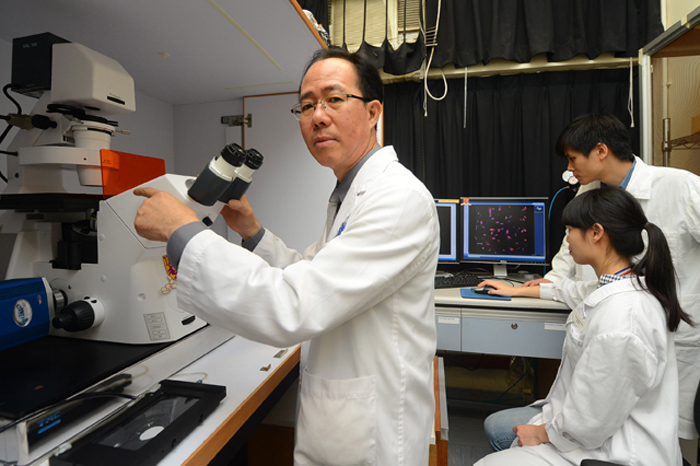

The research team comprising scientists at CUHK and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine is led by Prof. Fung Ming-Chiu from the School of Life Sciences.

Their new findings reveal that primary cells isolated from mouse, rat and ferret could also reverse apoptosis. They call the phenomenon 'anastasis' (Greek for 'rising to life').

It is generally believed that once the cells pass critical checkpoints, the dying process is irreversible. Such checkpoints include cell shrinkage, breakdown of mitochondria, condensation of nucleus, breakdown of DNA, and activation of a decisive group of 'executioner' proteins called caspases, which destroy a large number of cellular targets.

Professor Fung compares chemical-induced apoptosis to demolition of buildings. 'During the process of apoptosis, enzymes break up chromosomal DNA like demolition workers taking down a building. If you say: "Well, I don't want to take it down now, please rebuild it." Then, the DNA damage has to be repaired. But DNA repair may go wrong. It's like you won't have a hundred-percent original after you have taken down and rebuilt a historical building. The surviving cells may bear chromosomal abnormalities and acquire mutations. Certain mutations will lead to uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation. That means reversal of apoptosis may cause normal cells to become carcinogenic.'

In the case of cancer cells, the cells that undergo reversal of apoptosis after anticancer treatment could acquire new mutations and thus transform into more aggressive and metastatic cancers.

The good news is that the research team found that soybean extract, with an anticancer compound known as genistein, could inhibit the recovery from apoptosis in cancer cells. In future studies, the researchers plan to test the extract on animals and carry out human clinical trials.

The research team's finding provides a new route to understanding the basic biology, and suggests new therapies such as enhancing the effect of chemotherapy by inhibiting anastasis.

The research was funded by the Lo Kwee Seong Biomedical Research Fund, the Lee Hysan Foundation, the University Grants Committee Area of Excellence Scheme, and Saskia van der Stap.