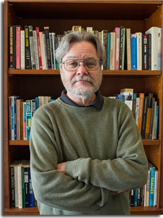

ETA Ceremony | Professor HO Chi Ming | Professor Gordon MATHEWS

|

"I tell my students that grades don't matter—what matters is their own effort to think for themselves. I say to them, 'Remember: really stupid people sometimes get A's, because they worry so much about getting good grades that they forget about things that may be more important in life.'" |

||

Professor Gordon MATHEWS, Department of Anthropology |

||

|

General Education Teaching Philosophy

I love the subjects I teach. I believe that if my students can understand these subjects, their understanding of the world and of their own future lives will be greater. I teach three General Education classes, UGED2980 Meanings of Life, UGEC2990 Globalization and Culture and UGEC1681 Humans and Culture. I have designed these courses with my own undergraduate experience at Yale University in mind—what are the courses that might have taught me most about the world that I never had the chance to take? In all three of these courses, I use my own books, as well as many other books, as class readings, not because I think they are particularly good, but simply so that students can better understand how I think, and can respond. Students who can effectively criticize my books in their essays written for my classes often get A's.

One key element of my teaching is class discussion. I never lecture for more than twenty minutes at a time. Interspersed with this lecturing, I offer classroom discussion questions, questions dealing with issues relating to the lecture and readings. For example, in a class on globalization and mass media, I might ask, "If you were the ruler of a poor country, would you block the internet? Why? Why not?" In a lecture on culture and gender, I might ask, "Why do some men like to look at pictures of unclothed women, but most women don't like to look at pictures of unclothed men?" In a class on meanings of life in religion, I might ask, "Would the world be better if we all believed in God? Or would it be better if we all didn't believe in God?" In a lecture on contemporary cultural identity, I might ask, "Do you love your country?" first to Mainland Chinese, then to Japanese, then to Americans, and finally to Hong Kong students in the class, to get a debate started. Then I might ask, "Should people love their country? Why? Why not?"

In these discussions, I am very careful not to provide any "answers": the purpose of these questions is to get students to think for themselves. I don't ask students to raise their hands if they want to speak—I simply call on students who look at me. I later ask some of these questions in my take-home midterm and final examinations. Class discussion thus forms an essential part of class learning and teaching. Students do need to learn facts, and I am careful to teach a framework of factual knowledge. But most important is that students learn to think for themselves on the basis of facts. I don't want to teach students to hold a particular opinion but rather to be able to think clearly, logically, imaginatively, and fearlessly in arriving at their own opinion, whatever that opinion may be.

|

Underlying all this is the deep affection I feel for students. These students remind me of myself forty years ago, and I have a sacred obligation to teach in the best and most innovative way that I can. I often emphasize to students that although I must grade them, grades don't matter—what matters is their own effort to think for themselves. I say, "Of course I'd prefer you to do well. But at the same time, remember: really stupid people sometimes get A's, because they worry so much about getting good grades that they forget about things that may be more important in life. And really wise people sometimes get C's. Don't ever let grades define who you are: you are much more than that." |

My aim is that decades from now, when students are in the midst of their careers and lives, they will remember an insight they gained from my class that can help them in their understanding. If someone remembers something they learned in my class many years earlier, and uses it to more fully comprehend their lives and world, then my teaching will have been a success. This is why I teach.