CUHK Study Discovers Pathway That Links to Cognitive Flexibility Dopamine Dysregulation May Lead to Ability Impairment

Neuroscientists from the School of Biomedical Sciences of the Faculty of Medicine at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) have achieved a breakthrough in identifying a critical mammalian brain pathway which allows a subject to abandon an old concept or strategy and adopt a new one in response to a change in the environment. The result of their study was recently published in the international scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA.

Cognitive Flexibility has close links with neuropsychiatric diseases

Cognitive flexibility refers to our ability to respond adaptably to changes in environment or a rule, so as to avoid making mistakes. For example, if your office has moved to a new floor, at the beginning, you may often mistakenly go to the floor where the old office was located. Most people only make such a mistake once or twice but some may need more time to adapt to the change. It is how quickly we can change our course of action to a new and more effective one when an old strategy is not working. This ability is essential for almost all our daily activities.

Cognitive flexibility is related to how well our brain can handle and manipulate two concepts at the same time, or switch from one concept to another. In fact, in a number of neuropsychiatric diseases, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia, this cognitive flexibility could be impaired. Moreover, in some neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, the sometimes observed personality change of the patients in becoming more “stubborn” may also be the consequence of reduced cognitive flexibility.

Depletion of dopamine may lead to impairment in cognitive flexibility

The brain circuitry underlying cognitive flexibility has not been very clear and this study led by Prof. Wing Ho YUNG and Prof. Ya KE, from the School of Biomedical Sciences and the Gerald Choa Neuroscience Centre of the Faculty of Medicine at CUHK, has provided a clue.

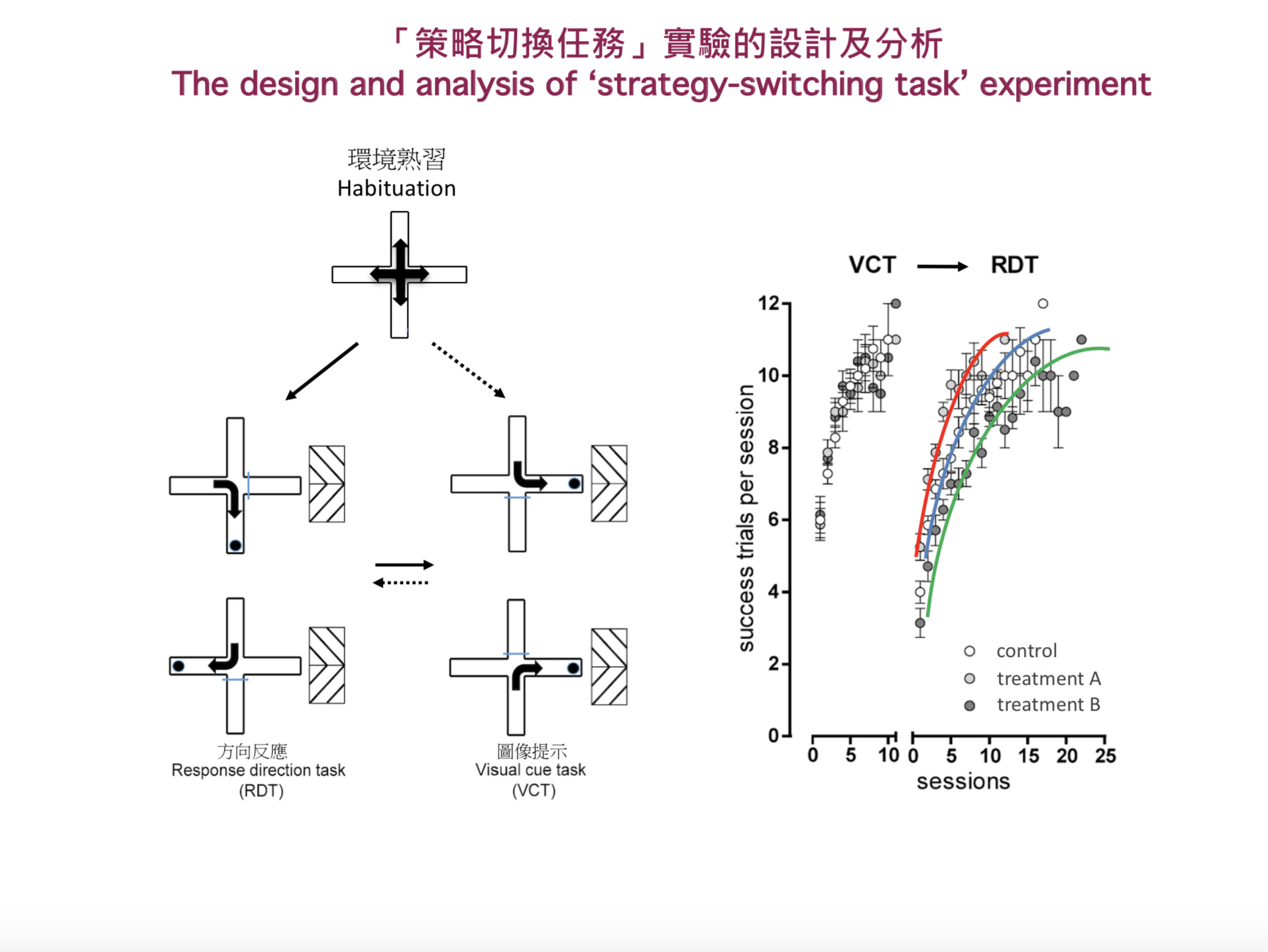

Based on a strategy-switching task conducted on experimental mice, researchers first trained them to make a decision at the cross-junction of a maze according to a rule in order to obtain food, e.g. always turn right. After the mice learned the strategy, researchers changed the rule, e.g. follow the visual cue regardless of the direction. Researchers then studied how many and what kinds of errors the mice would commit before and after mastering the new strategy.

Prof. Wing Ho YUNG, Professor of the School of Biomedical Sciences and Director of the Gerald Choa Neuroscience Centre at the Faculty of Medicine at CUHK, explained, “By applying state-of-the-art research techniques including optogenetics, patch-clamp electrophysiological recording and development of novel virus-based molecular research tools, our team confirms that strategy-switching ability is a function distinct from learning a new strategy. More importantly, we discovered a critical circuitry in the brain involving the interconnection between the prefrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens in this behaviour. Furthermore, by manipulating this particular pathway, we can artificially increase or decrease the ability of the animal in switching from one strategy to another.”

Another key finding of this research is related to dopamine, a chemical acts as a messenger between brain cells. The team found that dopamine released in the nucleus accumbens can regulate the signals coming from the prefrontal cortex and is essential in facilitating task-switching ability.

Prof. Ya KE, Associate Professor of the School of Biomedical Sciences and investigator of the Gerald Choa Neuroscience Centre at the Faculty of Medicine at CUHK, commented, “The findings may therefore be able to explain why, in some brain disorders like Parkinson’s disease, obsessive compulsive behaviour and attention deficit hyperactive disorder, the patients are less flexible in their behaviours and often stick to one and only one rule to do things. These are likely due to dysregulation of specific dopamine systems in the brain. These findings from basic research could promote a better understanding of the neural circuitry of strategy-switching flexibility and may help in identifying novel therapeutic targets for patients suffering from impairment in cognitive flexibility.”

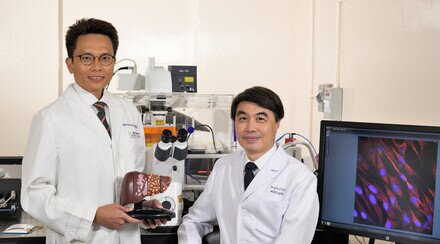

A recent study conducted by the School of Biomedical Sciences of the Faculty of Medicine at CUHK has achieved a breakthrough in identifying a critical mammalian brain pathway which allows a subject to abandon an old concept or strategy and adopt a new one in response to a change in the environment. (From left) Associate Professor Ya KE, Postdoctoral Fellow Hongyan GENG and Professor Wing Ho YUNG from the School of Biomedical Sciences of the Faculty of Medicine at CUHK.

Another key finding of this research is that dopamine released in the nucleus accumbens can regulate the signals coming from the prefrontal cortex and is essential in facilitating task-switching ability..

Based on a strategy-switching task conducted on experimental mice, researchers study how many and what kinds of errors the mice would commit before and after mastering the new strategy.