State-of-the-art laser imaging shines fresh light on the distant past

Prof. Michael Pittman’s research uncovers how pterosaurs took off from water 150 million years ago.

(Photo credit: Julius T. Csotonyi)

A CUHK palaeontologist’s leading edge laser imaging technique that could revolutionise palaeontology is providing new answers to age-old questions about how early creatures lived, transforming our understanding of prehistoric biology and ecology thought to be lost to the mists of time.

Important advances in prehistoric ecology

Laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF), an imaging technique that uses high-powered lasers to cause specimens to exhibit fluorescence, has now given CUHK palaeontologist Prof. Michael Pittman of the School of Life Sciences newly undiscovered details from even the most exhaustively researched specimens. Thanks to this, Prof. Pittman’s inventive research has led to 25 professional papers covering his remarkable discoveries.

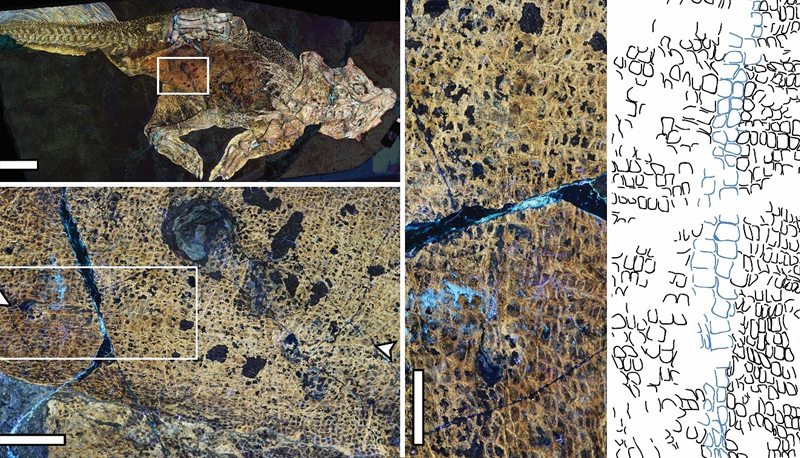

For example, by applying LSF imaging to a 125-million-year-old fossilised skin specimen of Psittacosaurus, Prof. Pittman’s team uncovered the first fossil evidence to show that egg-laying dinosaurs had umbilical scars: in other words, belly buttons. The specialised imaging technique identified distinctive scales surrounding a long umbilical scar that were formed when the dinosaur hatched from its egg.

‘Whilst this beautiful specimen has been a sensation since it was described in 2002, we have been able to study it in a whole new light using novel laser fluorescence imaging, which reveals the scales in incredible detail,’ said Prof. Pittman.

The LSF image of the whole Psittacosaurus specimen showing the location of the umbilical scar.

(Photo credit: Bell et al. 2022)

Further research determined how small prehistoric flying reptiles achieved take-off from water surfaces, using LSF imaging to reveal details of preserved soft tissue from the wing membranes and webbed feet of a small pterosaur. Aerodynamic modelling showed that the pterosaur launched itself from water with folded wings and webbed feet, similar to how ducks take-off from water today.

Prof. Pittman’s team also broke new ground by using quantitative fossil evidence to challenge assumptions about the diet of a 120-million-year-old bird family called Longipterygidae, discovering that the prehistoric birds, commonly believed to eat fish, fed mainly on invertebrates. This furthers understanding of the evolution of birds and sheds light on both past and present ecosystems.

Innovation beyond palaeontology

Prof. Pittman has also applied LSF imaging to archaeology, studying excavations, wall paintings, floor mosaics, pottery and glassware held by the Verulamium Museum in the UK. This uncovered many new details, including new information about how different objects were produced. Imaging of a Roman vase revealed human fingerprints on its surface, apparently created by a Roman worker handling the vase while its surface was still wet.

Prof. Pittman’s projects involved a wide range of international experts and academics from a number of institutions, including the Foundation for Scientific Advancement in Arizona and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in the US; the University of New England in Australia; Unidad Ejecutora Lillo in Argentina; and University College London in the UK; among others.

Read more:

- CUHK palaeontologist first to reveal a dinosaur belly button using laser imaging

- CUHK suggests that pterosaurs took off from water 150 million years ago like ducks do

- Small flying reptiles that do great wonder

- CUHK palaeontologist investigates the diet of prehistoric birds to reconstruct past and present ecosystems

- CUHK applies cutting-edge laser imaging for the first time to reveal the hidden history of artifacts