From Prosecuting to PeacekeepingCUHK law professor wages war against verbal atrocity

November 2017

Few lawyers can say that they have resisted the chance to become a partner in a law firm and moved to a different continent in the name of human rights. Prof. Gregory Gordon of CUHK's Faculty of Law has done it, twice.

His 2014 move to Asia, after having worked as a prosecutor at the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and as Director of the University of North Dakota Centre for Human Rights and Genocide Studies, was motivated in large part by a desire to work on a continent where international criminal law (ICL) has significant roots in the post-World War II trials of Japanese war criminals and contemporary resonance in the current UN-backed trials of Khmer Rouge leaders and recent allegations of atrocities in places such as Myanmar and Sri Lanka. And to do that work at CUHK Faculty of Law, with one of the academic world's best ICL cohorts, was an opportunity he could not resist.

But Professor Gordon's first overseas move to help the victims of mass human rights violations took him to Africa nearly two decades ago. Leaving an opportunity to settle down to a conventional legal career after earning undergraduate and law degrees at Berkeley, he served as a prosecutor at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). The ICTR was set up by the United Nations to prosecute the architects of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, during which Hutu extremists slaughtered up to 800,000 minority Tutsis and moderate Hutus in just 100 days.

Serving as Legal Officer and Deputy Team Leader at the ICTR for the landmark 'Media' cases, the first international post-Nuremberg prosecutions of radio and print media executives for incitement to genocide, Professor Gordon was part of a team charting a new era in international criminal justice. At the same time, however, he realized there were gaps in international law that had to be addressed. After leaving the ICTR, he began writing scholarly pieces on the law governing the relationship between speech and atrocity.

That scholarship recently culminated in his authoring a new book, Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition. Published this summer by Oxford University Press, it is the first comprehensive study of international speech crimes. Professor Gordon hopes that his book will not only serve as a resource to understand how international law should be reformed, but also as a warning for what can happen if it is not. 'As the world is becoming more polarized and violent, we are at a point in history where hate speech issues are coming again to the fore and they need to be dealt with urgently,' he says.

To illustrate his point, Professor Gordon cites Donald Trump's remarks as a presidential candidate that US soldiers should torture ISIS combatants and murder their families. Current international law does not criminalize incitement to war crimes, letting Trump off the hook. However, under Professor Gordon's proposed new framework, an innovative set of reforms constituting what he calls the 'Unified Liability Theory', Trump could be considered criminally liable for his ISIS-related remarks. Under current ICL, incitement is limited to the crime of genocide. But the Unified Liability Theory would extend it to war crimes and crimes against humanity. And it would fill in many other gaps in this area of the law.

But Professor Gordon feels strongly that the law must strike the proper balance between criminalizing hate speech and protecting the right of free expression. And his book does that in various ways, including methods for ensuring rigorous analysis of all speech contexts, as well as media of dissemination. And, he adds, implementation of his groundbreaking framework will help too. 'Clearer laws through the proposed reforms will give less leeway for authoritarian rulers to justify blanket suppression of dissent, which also helps protect the legitimate exercise of free speech,' he explains.

While Professor Gordon's research on hate speech in the context of international crimes stems from his ICTR and US DOJ experience, the time he has spent at CUHK has allowed him to appreciate more deeply how hate speech manifests in much the same ways across the world. He has taught ICL at CUHK, coached the International Criminal Court moot team and supervised student dissertations on hate speech. And through his experiences in Hong Kong and around the world, he has found certain universal traits in what his book innovatively, and more accurately, terms 'atrocity speech'.

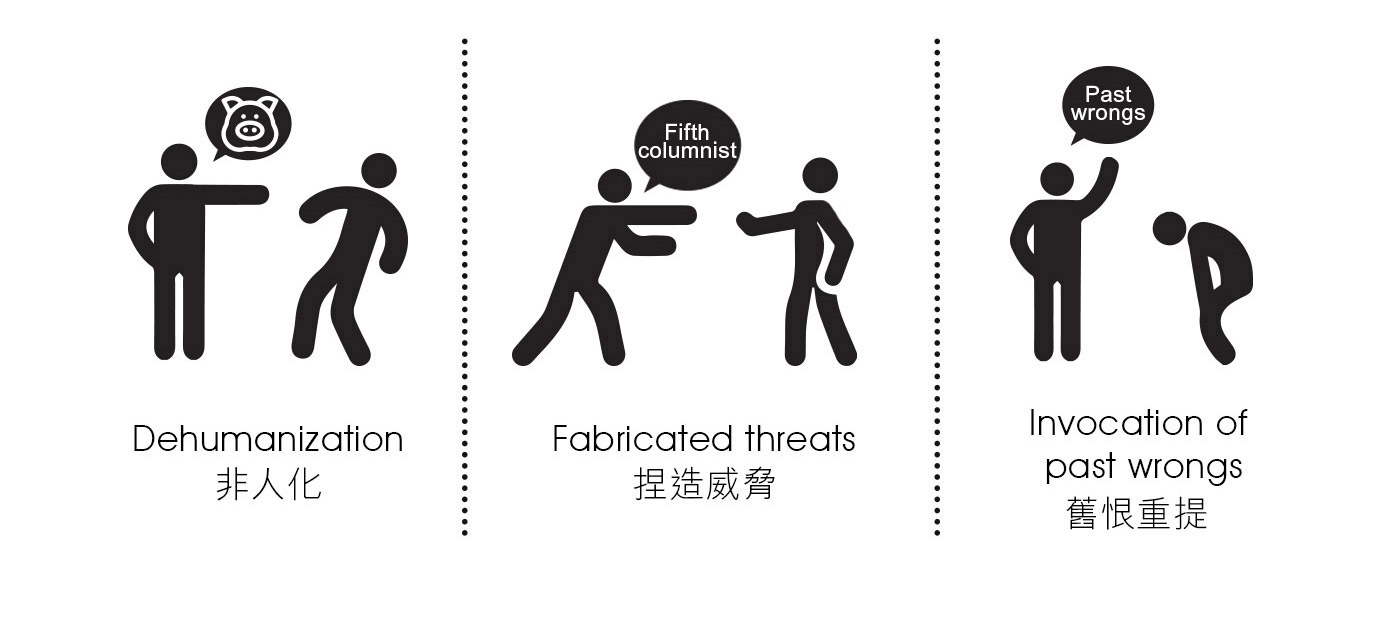

Professor Gordon broadly identifies three types of speech used to stir up state-sponsored violence and he has seen instances of all three in Asia.

The first is dehumanization. This, he says, can be seen in Myanmar right now, where Buddhist hatemongers are equating the Rohingya Muslim minority to dogs or fleas, among other subhuman creatures. The second sort of hate speech, fabricated threats, was featured during the Cambodian Genocide in the late 1970s, when Khmer Rouge officials denounced the country's ethnic minorities, such as the Vietnamese, as fifth columnists.

The third category, the invocation of past wrongs, was used in Sri Lanka to incite violence against the minority Tamils during the country's civil war between 1983 and 2009. Sinhalese leaders whipped up the majority population by invoking historic Tamil invasions from South India as being at the root of all modern problems. But, Professor Gordon notes, this kind of speech has been used in the service of atrocity campaigns against different minority groups on different continents throughout history, including against the Jews during the Holocaust and the Tutsis during the Rwandan Genocide.

Merely having good laws is not a cure-all, however, as Professor Gordon hastens to add. Legal reform should work in tandem with education, civil society initiatives and pluralistic media engagement. One way in which he is helping to make this a reality is by teaming up with the Yale Genocide Studies Program and PROOF: Media for Social Justice, a New York-based NGO, to organize an interactive travelling exhibit to educate the public on atrocity speech and the laws around it.

Moreover, Professor Gordon's scholarship is providing a framework for a multi-nation hate speech study being conducted by the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. And he is in discussions with the United Nations Development Programme and World Bank to use his Unified Liability Theory to conduct a one-country atrocity speech monitoring project.

Motivated by a deep belief in doing the right thing, Professor Gordon hopes that his work both on and off campus can help improve civic discourse and bring an end to the cycles of mass violence.