Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

A Ferryman of Life

Wallace Chan’s soul prescription for helping professionals

‘Suffering’ and ‘ferry’ share the same Latin root ferre, which means ‘to bear’ or ‘to carry’. ‘Suffering itself bespeaks unspeakable heaviness. What keeps us bearing it?’ This question has been with Prof. Wallace Chan for many years.

During his undergraduate studies at CUHK’s Department of Social Work, Professor Chan interned in a hospice and accompanied the terminally ill in their last stage of life. The unforgettable experience inspired him to explore issues of death, dying and bereavement. After graduation, he worked in the hospital’s geriatrics and palliative care divisions as a social worker to console the terminally ill and their families. Standing so close to suffering and mortality, he sometimes felt overwhelmed.

Among the patients he served, there were those diagnosed with cancers despite a healthy lifestyle. Some battled acute illnesses, having raised their children and just started retirement. He felt speechless whenever patients questioned why suffering had found them. A quadriplegic patient was very pessimistic and repeatedly told him that life was meaningless. Once he felt so depressed that he had to return to his office for a rest. He wondered, what’s there in life besides grief?

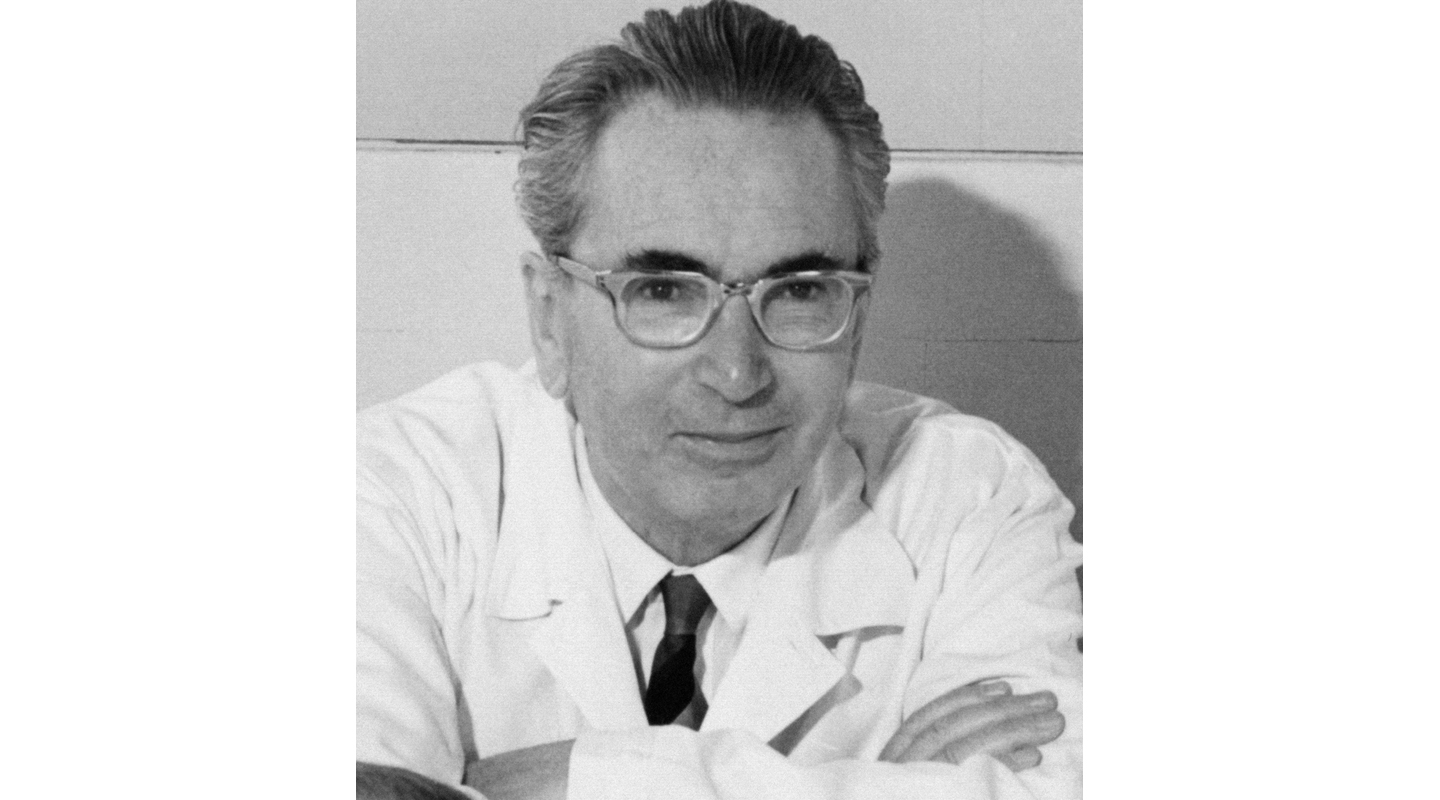

‘Suffering is a fact of life. But if you’re too concentrated on the current challenges, you’d miss the meaningful things around you. Even if this moment is filled with pain, I still trust that life is meaningful.’ This is Professor Chan’s insight from studying logotherapy. The Austrian Jewish psychiatrist Viktor E. Frankl is the founder of logotherapy. During the Second World War, he was imprisoned and tortured in a concentration camp. He struggled to survive in order to reunite with his family. He also helped prisoners with his medical knowledge and discovered meaning in suffering.

Freed in 1945, he learnt that his parents, wife and friends had died in the concentration camps. He wrote Man’s Search for Meaning in the same year to recount his experience in the Nazi camp. He quoted Nietzsche in the book: ‘He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.’ Instead of being crushed by a painful past, he lived his life to the fullest and traveled around the world to promote logotherapy. He held 29 honorary doctorates from universities around the world. He obtained his pilot's license at the age of 67. He even climbed the Alps when he’s 80.

‘Meaning exists. We don’t need to create meaning, but follow our pace to search for the lost meaning. As long as we keep searching with an open mind, life would give us an unexpected answer,’ said Professor Chan. The concept of ‘tragic optimism’ in logotherapy denotes that despair and disaster will not hamper humans’ search for meaning and hope. They still have the freedom to choose their attitude to cope with suffering. ‘Real optimism lies in trusting that life has its meaning and value despite the adversities.’

Professor Chan is a certified clinician in logotherapy and a fellow in thanatology. He has been teaching the University General Education course ‘Living with Grief’ since 2012. He hopes to create a space that helps students release their emotions and explore the issues of death, bereavement, grief and the meaning of life. He received the Exemplary Teaching Award in General Education in 2015. Many positive psychology courses focus on cultivating happiness, which may lead to suppression of emotions. ‘There’re good days and there’re bad days. We should also touch on our pains when we reflect on life. Separation and grief are natural. We experienced separation the moment we were born.’

He loves to get in touch with students. Due to the pandemic since 2020, he could only resort to online teaching but has learnt an unexpected lesson because of this. In the online course ‘Living with Grief’ last year, he discovered a lot of sit-in students. ‘I invited them to connect with me. A sit-in student told me his internship had been affected by the pandemic and he wished to use his spare time to attend the online class. His father with cancer attended the class, too. They were inspired by the discussions on suffering and life’s meaning. Humans are afraid of losing control, but life is filled with variables. Should we keep going in the journey, we would have unexpected encounters.’

Besides research in logotherapy, bereavement counselling and end-of-life care, Professor Chan also studies the well-being of helping professionals including bereavement counsellors and doctors, nurses and social workers in palliative care. They come face to face with life and death in the ward every day. If they can’t adjust themselves, they would be prone to burnout and compassion fatigue, have emotional issues or even give up their work. ‘Compassion’ comprises the Latin roots com (together) and passiō (suffering). How could the helping professionals walk an extra mile with the sufferers?

Major textbooks on bereavement counselling and thanatology generally focus on knowledge and skills. Not many centre on the frontline workers themselves. Professor Chan joined CUHK in 2010, with an aspiration to integrate his frontline experience as a medical social worker and staff training. He has interviewed numerous helping professionals who have been confronting death (death workers) on a regular basis. He also organized many experiential workshops to help participants pause to revisit what death work brought, feel their neglected emotions, reflect on life and death, and arrive at self-introspection.

‘Modern society prioritizes effectiveness. We can acquire skills to boost efficiency in life and at work. But self-introspection requires space to cultivate. The workshop participants learn that better understanding of their ‘selves’ help them better meet workplace challenges.’ Professor Chan has summarized two types of coping from the participants’ feedback in previous workshops: emotional coping (the ability to handle grief and helplessness) and existential coping (the aftershock from work on life and death values and meaning in life). A Self-competence in Death Work (SC-DW) scale was thus derived.

In 2012, Professor Chan started to invite his workshop participants to fill out the SC-DW scale before and after the workshop. The results indicated that the workshop helps enhance their self-competence and correlates positively to the meaning in life: At the same depression level, those who perceive more meaning in life tend to find themselves coping better with death work. The findings were published in 2019 in Death Studies. Later on, the team of the CUHK Jockey Club Institute of Ageing led by Prof. Jean Woo applied the SC-DW scale and found that those who attended the training sessions for three times or more have higher self-competence. A research team in Barcelona, Spain also applied the scale to study 106 nursing professionals who engaged in death work.

Looking back on his trajectory as a helping professional, he opines that sincere expressions and self-acceptance are very important. ‘Helping professionals often put up a professional front and seldom express their emotions. But why can't we cry? To shed tears means that we empathize with the sufferers. Tears do not mean weakness. We would only pile up our pains if we keep suppressing our emotions, which would edge us towards the precipice.

‘We should at our own pace release our grief and allow ourselves to be upset.’ Professor Chan then flashed a card that lists three things-to-do in a day: get up, survive and go back to bed. He added, ‘We should accept that we can’t solve all the problems right away. Being able to survive is good enough. The most important thing is to accept who we are at that moment.’

We are emotional being and have our unique grief experiences. ‘The loss of a beloved family member or a patient is worth our remembrance and grieving. The deeper the love, the deeper the grief. Grief can be lifelong. Love is also lifelong.’ To Professor Chan, the meaning at work lies in journeying and discovering meaning with the sufferers. Each step leaves a lifelong impact.

By jennylau@cuhkcontents

Photos by Eric Sin