Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

A Tale of Hands

At a time when holding hands may be hazardous

Mask wearing aside, keeping our hands clean has been the golden rule of these days. The first thing many of us do after stepping into our home would be washing hands, following that age-old precept we learned in kindergarten. Settling into their seats on the bus, posh young ladies take out little bottles from their handbags and spray their hands. Back at our CUHK offices, hand sanitizers have become our desk mate, and pink spray bottles distributed by the Department of Chemistry and the University Safety Office are handy and ready.

The Past Lives of Hand Washing

Washing our hands sounds like the most natural thing to do, but the truth is it is only in recent centuries the importance of hand washing to ward off illnesses and infections was recognized. The first call for clean hands is often thought to be sounded by Hungarian obstetrician Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865). In Europe in the 1840s, puerperal fever took the lives of many women giving birth. Intrigued by the phenomenon that mothers under the care of doctors and medical students died at a rate upwards of twice that of those cared for by midwives, Semmelweis tested a few hypotheses ranging from overcrowding, patients’ embarrassment in the presence of male doctors to religious rite, and tracked down unclean hands as the culprit: after the doctors and students performed autopsies in the mornings, they went into the maternity ward without sanitizing their hands, thus transferring the ‘cadaverous particles’ to the mothers and causing their death. Semmelweis went on to introduce a rigorous hand washing regimen that greatly reduced the number of deaths in the physician-run maternity ward. But his proposal, looking so modest and reasonable now, faced fierce opposition from the medical profession and cost him his job, if not life—courting criticisms for decades, he suffered a nervous breakdown and was admitted to an asylum in 1865, dying 14 days later of a wound on his right hand caused by the beating of guards.

Semmelweis’s brainchild had a posthumous birth: two years after his death, Scottish surgeon Joseph Lister promoted the idea of sterilized surgery with sanitized hands and surgical instruments, and French microbiologist Louis Pasteur put forward the germ theory and it became a widely accepted practice for surgeons to scrub their hands before operation in the 1870s.

Our City’s Symbiosis with Diseases

Our city is no stranger to public health crises, such as the bubonic plague of 1894, cholera and tuberculosis that raged during the postwar era. From 1947 to 1967, infections accounted for at least 60% of all local deaths. Fortunately, after the blows, Hong Kong emerged each time stronger and cleaner. During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003 and the swine flu outbreak in 2009, few would have forgotten the calls from the government to wash our hands before touching our facial orifices. In calmer times, sad to say, the virtue of hand hygiene seems to be more honoured in the breach than in the observance. The Personal and Environmental Hygiene Survey done by the Centre for Health Protection (formed in 2004 in the aftermath of SARS and holding daily press conferences now) in 2014 found that among 2,001 respondents, 6% did not wash their hands after going to the toilet, only 24% washed their hands before touching their eyes, nose or mouth, and less than 8% washed hands with soap and rubbed for some 20 seconds. In most counts, the male compliance rate was lower than the female’s. Will washing hands become a renewed ritual in town after the novel coronavirus becomes a thing of the past, with so much being lost?

Show of Hands, Show of Care

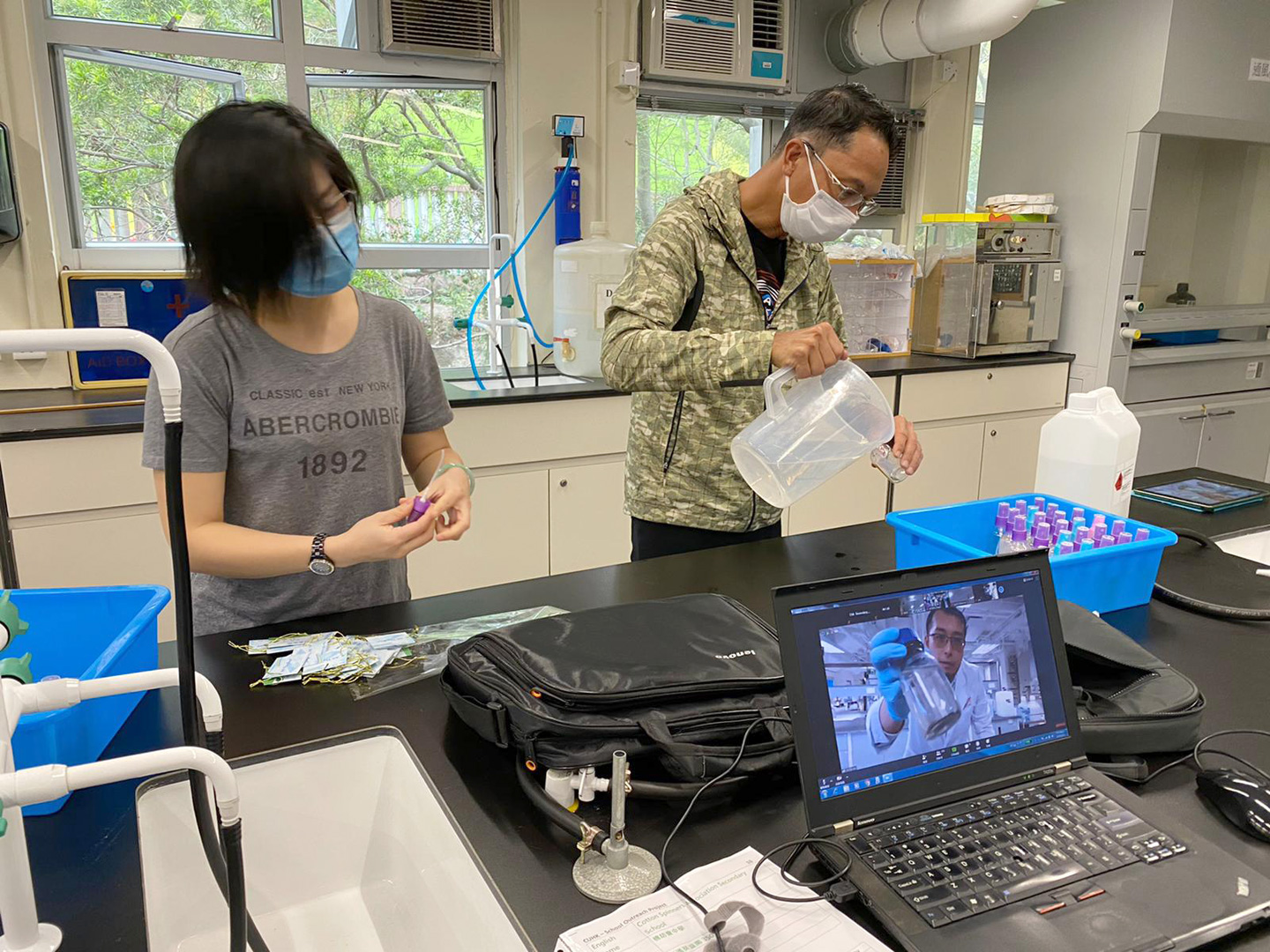

As the novel coronavirus first struck in late January, CUHK was swift to alleviate the shortage of hand sanitizers in the city by producing 1,900 litres of 75% alcohol handrub to give to University units as well as the wider community. The tale of CUHK showing her care through the making of handrubs was born of an idea: as the territory saw its first COVID-19 case on 23 January and hand disinfectants became scarce, Prof. Dennis Ng, Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Professor of Chemistry, thought of mixing the much coveted liquid himself leveraging on the labs and excellent facilities in the University. He enlisted his colleagues and students in the Department of Chemistry and also the University Safety Office to produce the solution. A video was shot of the making process, from the preparation of raw materials to mixing, filtering and bottling. It went viral, accruing a viewership of 230,000 within days. Many a non-governmental organization (NGO) called in to make queries, and the I‧CARE Centre for Whole-person Development helped line up 36 non-governmental partners to distribute the handrubs to elderly homes, special schools and residential child care centres.

‘We want to share even when supplies are low—that’s the spirit of giving we want to uphold,’ remarked Professor Ng. ‘Over half of the handrubs we made went to the hands of the elderly and the disadvantaged, who are most at risk of getting infected.’

Meanwhile, money, efforts and resources were pouring in from graduates heeding Professor Ng’s call. A former student of his got in touch and offered to donate non-alcohol disinfectants produced by his company to the NGOs. Sixty-seven medical graduates in the class of 2000 raised $33,500 for the purchase of raw materials and bottles, whereas Pricerite, run by an alumnus, also gave 10,000 bottles to the University. Two alumni associations, Convocation of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Federation of Alumni Associations of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, played a huge part in reaching out. With the help of CUHK School Heads Alumni Association, raw materials for 820 litres of alcohol-based handrubs were brought to 18 high schools for on-spot mixing, while four outreach sessions were arranged from late February to early March in Tin Shui Wai, Sham Shui Po and Ma On Shan that saw alumni and students producing the handrubs in the mornings and giving them away in the afternoons. Long queues formed outside the distribution counters, with CUHK members approaching the elderly and those vulnerable to furnish them with the handmade amulet bottles.

As the shortage of handrub supply eases, should the University still be making them? ‘The handrubs are now available on the market with a high price tag,’ said Professor Ng. ‘If possible, we would continue making handrubs, as the cost is lower and we can cater to those in need. Finally, through this initiative, I hope to convey the message that chemistry can be down-to-earth.’ He continued, ‘It’s the same with every discipline: when there’s a will, there’s a way you can tap into the wisdom of your subject and do something for the community.’

Handmake Your Way to Health

Even if you are not a chemist and haven’t got a lab, good news is you can make a handrub yourself. The CUHK formula makes use of isopropyl alcohol, which has a slightly more complex structure and better antiseptic properties than ethanol, another type of alcohol on World Health Organization (WHO)’s recommended formulations. Be sure to get hold of ethanol or isopropyl alcohol, as they are sometimes confused with methanol, a kind of highly toxic alcohol used in industrial settings.

‘Alcohol is highly flammable,’ said Prof. Yeung Ying-yeung, Chairman of the Department of Chemistry. ‘When transferring it from one bottle to another, or mixing it with other ingredients at home, remember to keep away from a flame or heat source, and keep the environment well-ventilated. Alcohol at high concentration can be harmful to humans, especially babies.’

‘Wear gloves and mask, goggles or glasses when handling hydrogen peroxide, which is corrosive in high concentration. The ingredient is used to inactivate bacterial spores in the solution and is not active. Dilute it to 3% as required by WHO.’

Does handrub come with an expiry date? Professor Yeung said, ‘Not in a theoretical sense. But alcohol is a volatile organic solvent which easily evaporates. Screw the cap tightly when it’s not in use—or the alcohol would evaporate and lower the concentration, hence detracting from its antiseptic properties.’

To Clean and To Care

Moisturizing weighs as much as sterilizing, as alcohol handrub becomes many’s personal accessory. ‘Our formula, based on WHO’s, contains glycerol, which is gentler to the hands,’ said Mr. Ralph Lee, Director of University Safety. To those with sensitive skin most vulnerable to alcohol, here’s the secret: get a bottle of glycerine—not glycerol as the pure form, but glycerine that contains 95% or less glycerol—from pharmacies, dilute it five-fold or more and apply on the hands or other skin areas. A colourless, viscous, sweet-tasting liquid belonging to the alcohol family, glycerol is a staple ingredient in skincare products, and works like a sponge that pulls in water from the environment and moisturizes the skin around the clock.

A pair of hands can spin many tales—of the dogged insistence on truth and the saving of lives over one’s interests and life; a lofty idea that materializes into the caring culture of CUHK; the sagacity of making good use of resources and doing things ourselves for our own and others’ good. In mockery to their affluence, Hong Kong and the world can still see deprivations and impoverishments. Coming on the heels of the pandemic would be tides of unemployment; but academia and civil society have never been far from each other, with one taking in the other’s wisdom and tending to the other’s needs. The 1,900-litre alcohol handrub produced by the University may seem like a drop, but our resolve and solidarity shall flow into an ocean that cleanses both our hands and soul. After all, what better way to combat the insidious virus than to show our ‘sunny’ sides—to be generous, courageous and upright?

Amy L.