Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

Minds Speak, Information Flows

Rosanna Chan co-invents EasyDial to give voice to the voiceless

If you grew up in Britain during the 1990s, chances are that you would have heard a certain telecommunication company’s slogan on TV—‘It’s good to talk’.

Indeed, many of us take communication for granted: it is easy, comes naturally with us, and most regard it as a fundamental skill we possess as humans.

But what happens if you want to communicate but are unable to do so?

‘The ability to communicate—the power to send and receive meaningful information—is certainly a unique aspect of mankind,’ said Prof. Rosanna Chan of the Department of Information Engineering. ‘Sadly, some people are born with an inability to speak or to express themselves with ease.’

Born and grew up in Hong Kong, Professor Chan finished all of her degrees (BEng, MPhil, MEd and PhD) at CUHK. Like most engineering researchers, she has a knack for science and logic; unlike most engineering researchers, however, she is also a ‘people person’—or, to be exact, an ‘information-theoretic’ people person.

‘My research always focuses on “information” and its interactions with mankind. To me, an engineering researcher has an inevitable responsibility of advancing technology for humanity,’ explained Professor Chan.

Given Professor Chan’s drive to contribute to the society, it is not difficult to comprehend why she would try her utmost in developing a cloud communications system for people who have complex communication needs (CCNs).

‘It all goes back to a seminar that I attended in 2013,’ Professor Chan reminisced. ‘It was my first time to come across the term “Augmentative and Alternative Communication” (AAC), which is defined as the ways and methods to complement communication for those who have motor or cognitive difficulties in conducting daily communication, including people suffering from dyskinetic cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorders, and dementia.’

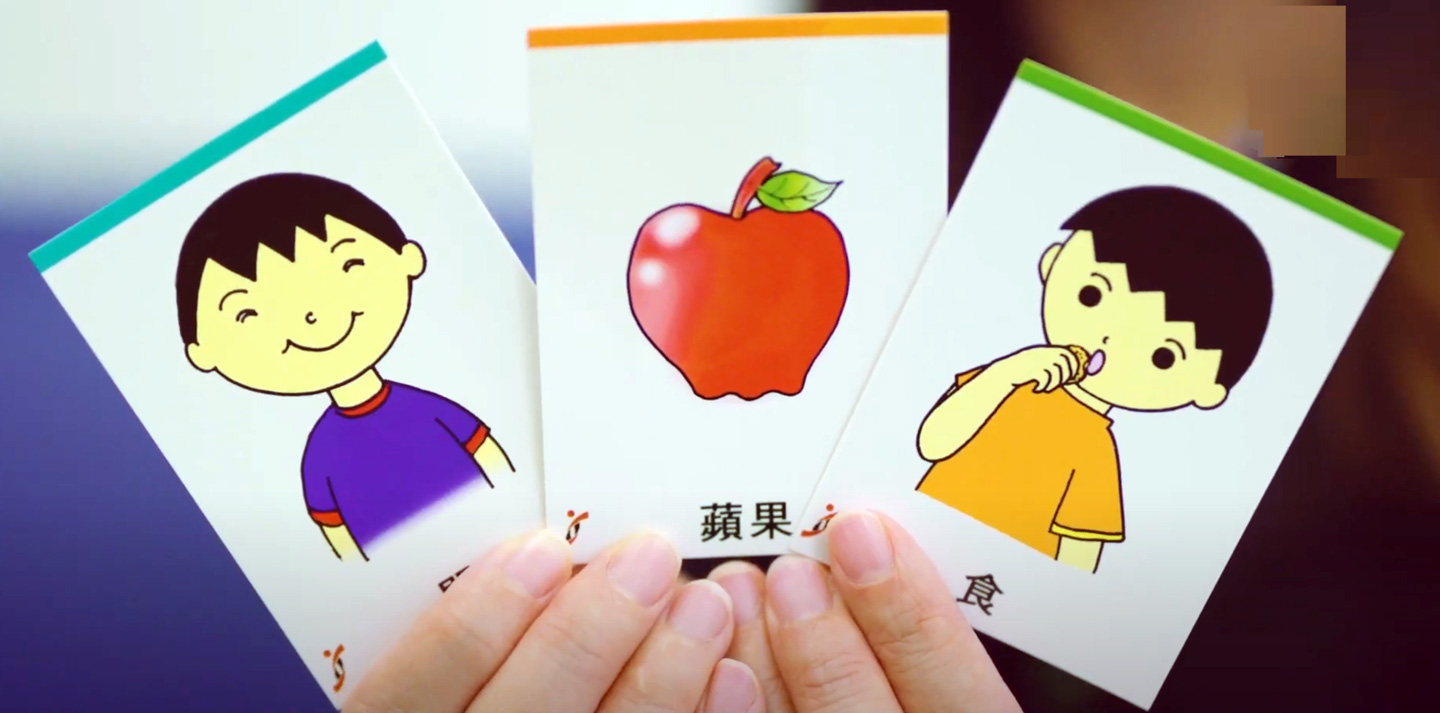

At that time, AAC mainly relied on paper picture cards and stand-alone offline mobile apps to assist people with CCNs. Nevertheless, enabling them to conduct long distance communication like mobile-phone conversation, especially for those who can barely control their body movements voluntarily, was an unexplored territory.

And then Professor Chan had a eureka moment. ‘AAC is literally a real-world example of Claude Shannon’s general communication model, which, in principle, means that information, characterized in the form of a message, should be transmitted from a sender to a receiver in such a way that the integrity of the message must be maintained and can also be understood by the receiver.

‘So I thought to myself, “Is it possible for people with CCNs to communicate better by making use of the recent technological developments and Shannon’s information theory?”’

Following the epiphany that she had right after the seminar, Professor Chan and her team collaborated with SAHK, an association which provides services and facilities for persons with neurological impairments, and spent about seven years to develop the world’s first-ever real-time cloud AAC system for people with severe communication disabilities. They called it ‘EasyDial’.

‘EasyDial is a mobile app which converted and digitized paper-based AAC cards into clickable pictures, which are then shown on users’ screen. When the sender selected and clicked on a picture, the respective Cantonese words will be uttered in the receiver’s device in real-time.’

This is how EasyDial works: imagine a person with CCNs wants to have a mobile phone conversation with the others. Upon calling and connecting to the receiver, a whole page of dynamic pictures recommended by the cloud server will then appear on the screen. Each picture is actually a digital image representing a certain word (for example, a person pointing his/her finger to himself/herself is equivalent to the word ‘I’). So by clicking on the pictures one by one, the sender can then send out a complete sentence to the remote receiver, resulting in what Professor Chan describes as ‘a real-time telephone call’.

‘Our app provides a convenient way for users to engage in daily communication, allowing them to participate in our society in a more active manner.’

With EasyDial, people with CCNs can now have more autonomy to enjoy the little things in life. ‘Take food delivery, for instance. Users can actually use our app to order food on the phone. In fact, SAHK has their own social enterprise café and we have tried out our app there. From their feedbacks, EasyDial users generally have no problem in placing their orders. In the near future, we hope they can order food by themselves wherever and whenever they want.’

Aside from user experience, the success of EasyDial is also backed by various scientific performance evaluations. ‘We have performed comprehensive studies on 33 participants who have severe communication disabilities. According to the results, participants who used EasyDial can utter about 67% more content in a conversational sentence than those who used traditional AAC methods. Comparing with the statistics provided in related existing literature, this is quite a significant improvement.’

The concept and theory behind EasyDial may look simple and easy, but to bring the whole system to life is totally another story. ‘We took innumerable rounds of trials, adaptations and developments before we can finalize and productize our work.’

Here is an example to illustrate one of the hardships Professor Chan had encountered: certain groups of users might have difficulty selecting the pictures from their screen, so she and her team would have to adjust variables like screen dexterity to increase the sensitivity. But after adjustment, some might then find the screen too sensitive such that a single click might result in multiple repeated selections on the same picture, therefore they need to solve the new problem, bearing in mind the pre-existing complications when figuring out the solution.

‘Throughout these seven years, we have worked closely with speech therapists, targeted end-users and also their family members to find out all of the problems and, ultimately, tackle them head on,’ said Professor Chan.

Fortunately, hard work does pay off, and in Professor Chan’s case, the Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Commission saw the innovativeness in her system and funded her project twice.

But Professor Chan does not stop there. ‘A good deal of work remains to be done,’ she stated. Her next step is to expand the user-base of EasyDial as far as possible. ‘In addition to users from SAHK, we are going to make the service available to other rehabilitation service providers in Hong Kong and see if the system can be used in the speech therapy and communication training sessions.’

Recently, Professor Chan has collaborated with researchers from the Tokyo Metropolitan University and introduced even more technical capabilities to the AAC systems, including context-awareness and micro-location detection.

To people with CCNs, EasyDial certainly helps them to connect their minds to and make information reach the outside world. ‘Besides providing an alternative way of communication, I truly hope that my works, be it EasyDial or other associated research projects, can raise the community’s awareness on those suffering from communication disorders. Only by understanding the challenges faced by the minorities will our society become a harmonious and inclusive place for everyone to live in.’

By ronaldluk@cuhkcontents

Photos by adalam@cuhkimages & ponyleung@cuhkimages