Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

A Gut Feeling: CUHK gastrointestinal scientist's discovery of colon cancer markers

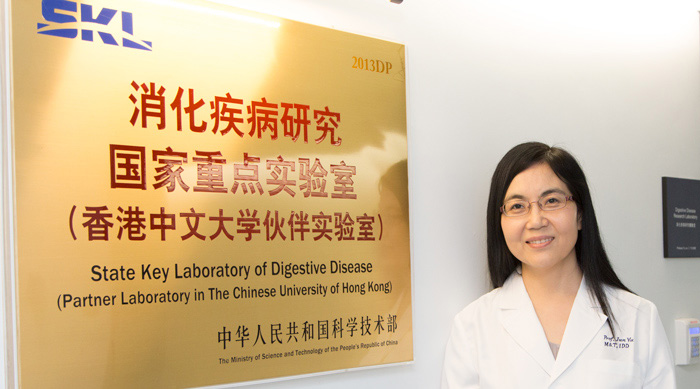

Prof. Yu Jun

Department of Medicine and Therapeutics

Colon cancer, once a rarity in Asia, is on the rise in the region. In fact, colorectal cancer became the most prevalent cancer in Hong Kong this year, overtaking lung cancer.

With bowel cancer currently hard and expensive to detect, CUHK's Prof. Yu Jun has taken it upon herself to find better ways of uncovering people who are at risk, early enough to stop the cancer in its tracks. Over the past few years, she has tracked down two markers that can be used to highlight which patients are on the verge of developing the disease.

Colon cancer used to be mainly a disease that afflicted the Western world. But it is becoming increasingly devastating in the East, where diets have cut down on vegetables in favour of meat, and lifestyles have become more Westernized. Lack of exercise is also a factor in Asia.

Conversely, thanks to better screening, the incidence of colon cancer has been declining in the West over the last decade. Patients over the age of 45 are most at risk and, with good medical advice, can catch the slow-developing disease early enough to prevent full-blown cancer.

The current method is to perform an invasive colonoscopy, where a fiber-optic camera is inserted into the anus of a patient and pushed via a flexible tube to examine the bowels. It's possible that way to detect polyps that, as the disease develops, turn into benign tumours known as adenomas at first, then blow up into full-blown cancer tumours.

Some of the issues with a colonoscopy are that it must be conducted in a well-equipped hospital and is expensive, often beyond the reach, literally, and means, figuratively, of rural residents in Asia. It also takes a considerable amount of preparation and time to conduct.

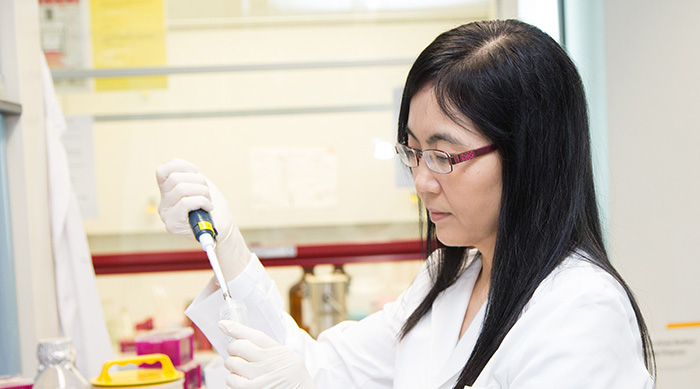

Professor Yu's work has sought to develop much less expensive and more easily administered ways of testing for colon cancer, such as examination of blood work, or the faeces of a patient. Analysis like that can be conducted in the field, taking the testing via mobile clinics to the rural poor. Urban residents could start the process with a quick visit to a general practitioner, potentially leading to a significant increase in patient compliance.

To that end, Professor Yu and her team have helped identify miR-92a and miR-135b, each one a large molecule that's part of a family known as non-coding ribonucleic acids, or RNA. Each is a useful marker in diagnosing colon cancer. The higher the level of Mir-92a and miR-135b, the more likely it is that the person has colorectal cancer – around 70 to 80 per cent of those high-scoring patients carry the disease.

"Normally when they approach the doctor, it's at a late stage. It has a low chance to be controlled, and the only way they can be cured is by surgery," Professor Yu explains. "We need to identify the patients at an early stage, ideally through using screening or noninvasive methods as a diagnostic tool."

Professor Yu, who holds a position in CUHK's Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, and her colleagues started screening for miR-92a in the faeces or "stool" of patients in 2008, publishing her findings in the journal Gut in 2012.

A stool-based bowel marker is more reliable than a marker detected by a blood test. Professor Yu, who also has a practice at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Shatin, then realized that another molecule, miR-135b, helped detect advanced adenomas in patients. She published her findings this year.

Professor Yu has applied for a patent for the bowel markers and is working with a company in Shenzhen to license it for the development of a detection kit, work that's under way for miR-92a since it was detected first. The plan is ultimately to screen for miR-135b as well.

"It is cheap and convenient – you just need a small amount of stool, 200 or 300 milligrammes, and then you can isolate and identify miR-92a and miR-135b," Professor Yu says. Both markers are produced by tumorous tissue, not bacteria, food or other normal cells found in the stool.

Early detection will then make it possible for surgeons to remove colon cancer at an early stage, and as a result cut down on the mortality rate of the disease.

"When we identified these markers, we were very excited," Professor Yu recalls. "It can help the population, people, patients. It can save lives."

By Alex Frew McMillan

This article was originally published on CUHK Homepage in May 2014.