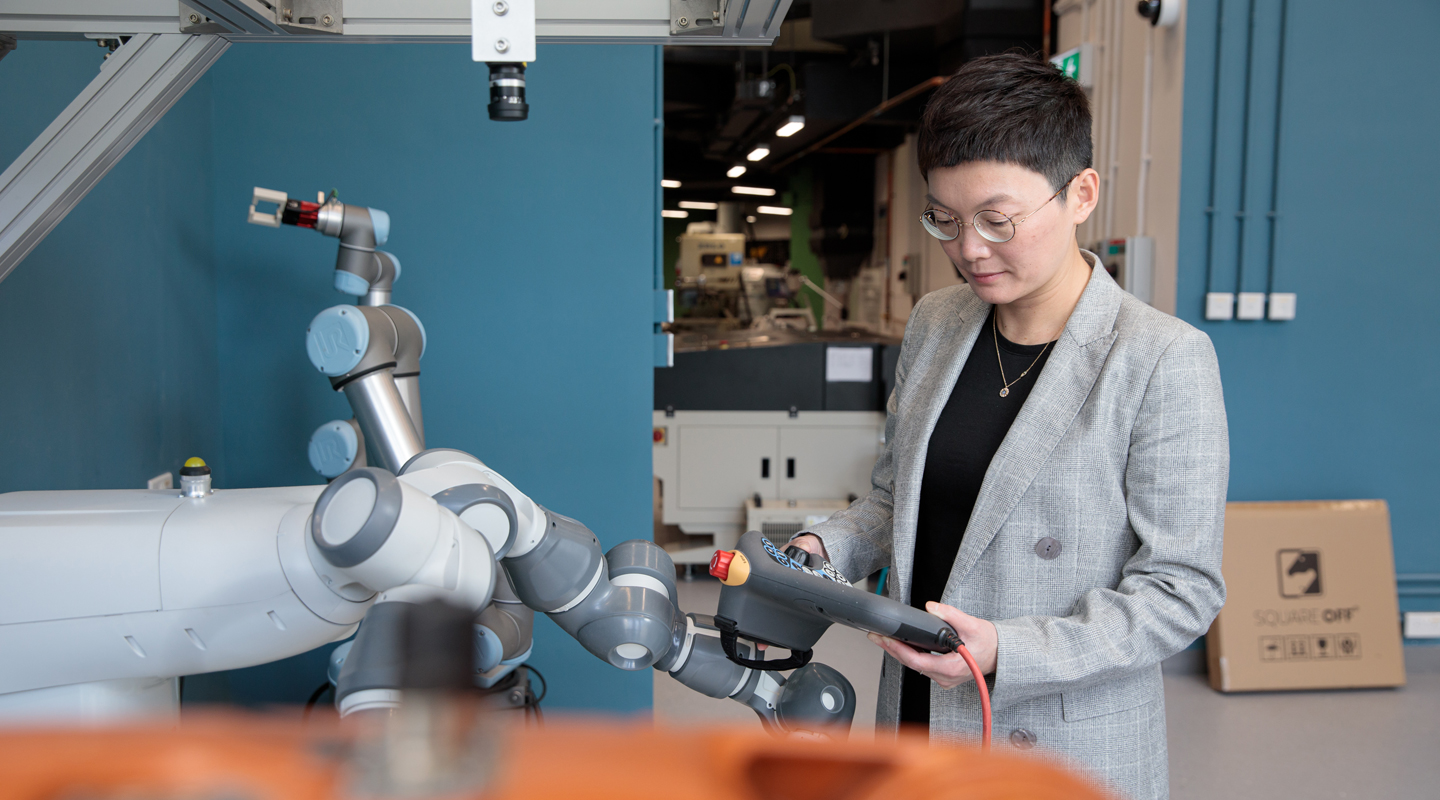

The Artifice of EternityFinding our place in the world of AI with Crystal Fok

May 2021

‘Do you think you’ll be replaced by a machine some day?’ I asked Dr. Crystal Fok.

If anyone knows what the future holds for her in the age of artificial intelligence, it is Crystal herself. When the engineer, now director of AI robotics platform and precise engineering at the Hong Kong Science and Technology Parks Corporation (HKSTP), was studying AI at CUHK, an intelligent, lifelike machine was for most of us something belonging to the fantasies of Asimov and Kubrick. Even for Crystal herself and those others working at the frontiers of automation, it was far from being practical.

As we now know, though, it is a very real possibility. What seemed to be the quarry of a wild-goose chase, as Crystal said jokingly of her research back then, was really just waiting to materialize, waiting above all for an explosion of textual and multimedia data from which machines could learn and grow to be functional—and come it did.

‘The financial sector was naturally one of the first to delegate tasks to machines, but more traditional industries are now also showing willingness to do so,’ said Crystal as she walked me through the state of AI here in Hong Kong. A matchmaker for developers of AI technology and those having a use for it, she has noticed a more welcoming, though still lukewarm, attitude towards AI as more people are having success with it. One sector eyeing the technology is the government, a recent client of Crystal’s being the rodent control team.

‘They want to show how effective their work is, so they installed thermal cameras at hundreds of locations in Hong Kong to help determine the numbers of rats before and after intervention. But at the end of the day, they would need someone to painstakingly examine all the footage and do the count. This is where AI filled in.’

In this case, the use of AI is a matter of convenience; in others, it could be that the machines can do what we cannot. The Architectural Services Department is one of the several other government agencies that Crystal has worked with. Their task is to estimate the costs of public works projects. What the HKSTP did was organize a challenge where bots were fed with government data about projects in the last 10 years and trained to guess the costs of a selection of completed ones.

‘Somehow the estimates were very close to the final figures, and the Department reckons bots like these can help produce more accurate quotations and justify its claims.’

But AI is not perfect. When the government first experimented with letting machines count the rats, the model had trouble distinguishing between the rodents and other warm, animate objects in the thermal footage: the result was a shocking report of there being more rats following control efforts. While this goes to show machines are not infallible, what is more worrying is we do not always know why they make mistakes. This is what experts call the ‘black box’.

People are working around this. To ensure their clients are getting results as reasonable as they can be, Crystal and her colleagues have recently launched a platform where clients are matched with bots that perform well specifically in, say, handling enquiries from customers of a certain age group rather than with a generic chatbot. Of course, though, this does not address our poor understanding of the way AI makes decisions. And as Crystal reminded us, machines are not necessarily the neutral, unprejudiced adjudicator that we can all count on.

‘The data with which we train a bot is absolutely crucial,’ she said. ‘It has to be complete and make sense, free of any bias. Think of the bot as a baby: teach it one language and not another, and that’s all it’ll be able to speak.’

For now, we are still going to have second thoughts about letting machines take our place, especially in cases where it can cost lives if the job is done poorly. But what if they come to master their craft like AlphaGo did with the game of go? Let us not forget, then, we are born multitaskers, moving constantly from one role to another, made to accomplish much more than cracking a board game. At least this is who Crystal is.

‘I didn’t know much about AI and all that when I was a kid. All I knew was I wanted to do something related to physics and applied sciences in university, and that was how I got into the Department of Mechanical and Automation Engineering,’ she said. Her exposure to the concept of automation, which, like AI, is grounded on a certain capability to think for oneself, led to her master’s thesis on how robotic arms can intelligently control their own movements. She took another leap as a PhD student, turning her attention to nanorobotics, all the while studying for a diploma in architecture.

‘It felt as though I was at war with myself,’ she said of her time going to and fro between two vastly different disciplines, one being so preoccupied with hard proofs and the other with the most fanciful of creations.

The evolution did not stop with her leaving university. She kept learning as an optics researcher at the Hong Kong Productivity Council, learning to promote frontier technology to a wider community at the Hong Kong Applied Science and Technology Research Institute, learning to be the bridge between developers and users from all walks of life at HKSTP. On reflection, it should be no surprise that as a CUHK student she would come to have so many interests and see her specialty so clearly as intertwined, after all, with the rest of human society. For this she is grateful for the college system, remembering still how it opened her eyes when she first met her fellow New Asia students, all having their own expertise, in the College orientation programme.

‘I’m just not keen on doing only one thing.’ This is what she has figured out and lived by over the years, and this is where the machines fall short.

When Yeats as an old man sails to Byzantium and sees the mechanical bird that will, unlike him, keep singing forever, he declares it ‘the artifice of eternity’. With a smartphone usually lasting no more than a few years, we are perhaps unsettled not so much by the thought of machines outliving us but by the thought of machines outwitting us, dethroning us as the masters of our lives once and for all.

‘I’d like to imagine a robot taking on my chores, but it’s going to have a tough time going much further. This very question is enough to stump it,’ said Crystal with a laugh, brushing off the existential crisis I confronted her with. It is not that she rules out the possibility of a general kind of AI capable of doing everything that we do. ‘There might be a day when the machines finally catch up, but that’s assuming humanity stops opening up new horizons.’

We have seen how hard that will be.

By jasonyuen@cuhkcontents

Photos by Eric Hong