CUHK Employees General Union

eNews (June 2018)

Editor-in-chief: Chan Yin Ha Vivian | Data: Wong Ka Po | Design and Typesetting: Cheng Chun Wing, Aidan Chau and Dora Lam (e-version) | Translation: Emily Ng

Special feature

The Fragmented University

(Issue editor: Chan Yin Ha Vivian Research: Wong Ka Po)

A year ago, we learnt that friends in different universities had been forced into part-time posts or their contracts simply discontinued. Some of them were from CUHK. Uniformly, the reason given was that "the department doesn't have the money". Why would a university be lacking money to hire teachers? Where did the money go? What circumstances and difficulties are these colleagues facing? As teaching jobs in universities get more casualised, what are the impacts on student learning? In the past year, we have raised questions with the university management, met with the UGC chairperson as well as colleagues concerned, and studied university and UGC data, with an aim of gaining a deeper understanding of the issue.

Why is there no money? What do we do then? There are several aspects to these questions:

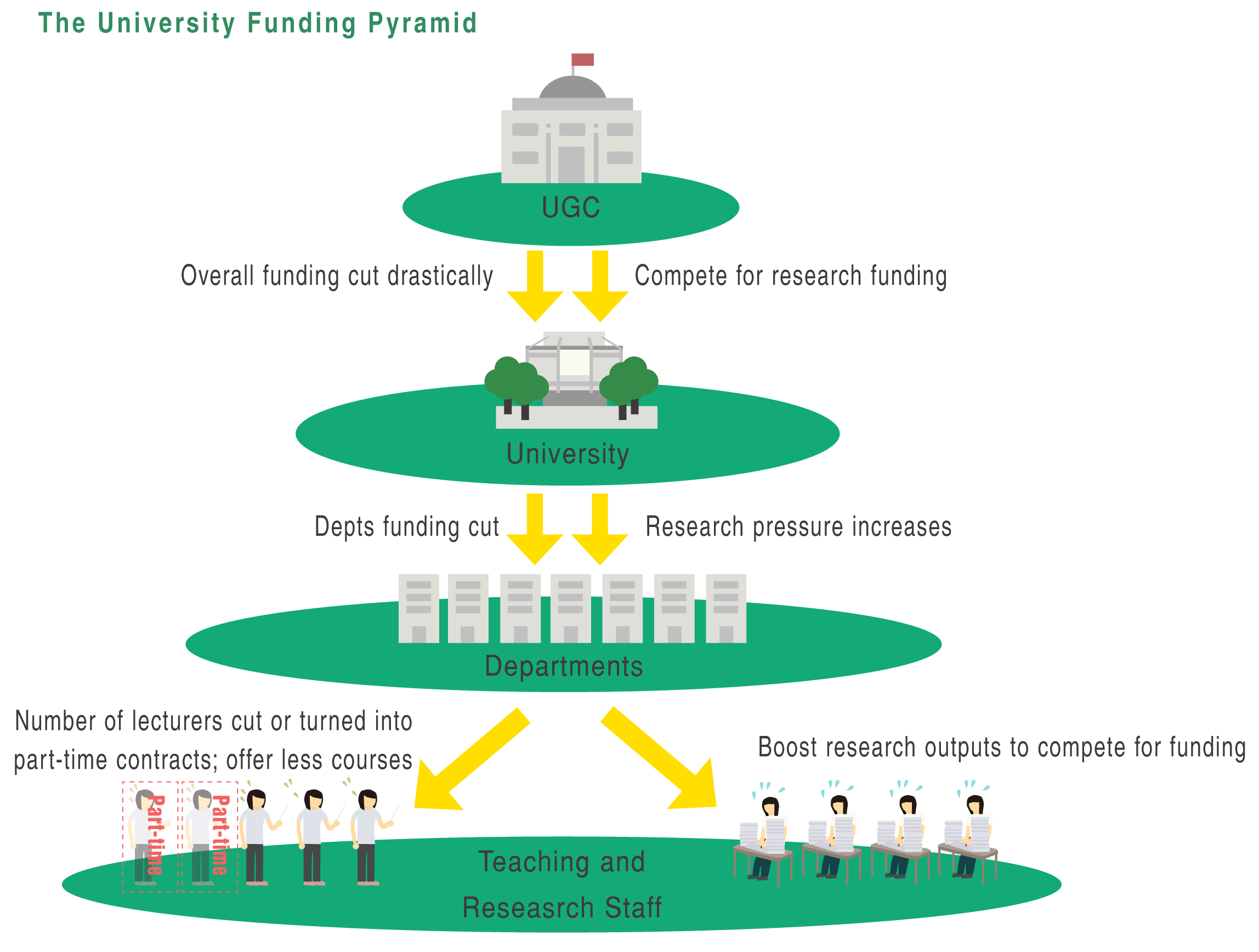

- Insufficient funding: One major cause is that the UGC has in fact drastically cut its funding to the universities. The unit cost per student in 2016-17 was 13% less than that in 2003–04. [ 1] With the funding not catching up with inflation, even the cleverest manager will find it a headache.

- Punishment on “unsatisfactory” research performance: RGC, a semi-autonomous organisation under the UGC, evaluates the research performance of the universities every few years. The evaluation results in turn affect the research portion (R portion) of the Block Grant. We are still living under the effect of the 2014 evaluation exercise. Even though that is the overall funding of the university, the university has its way of punishing those departments with “bad performance”, such measures may include budget cut or even freezing of account.

- There is not enough money. What cost can be cut? One would think that cutting the number of professor post would save more cost because the salary is higher. The answer is NO. They are needed for improving research performance. So it has to be the number of lecturers to be cut. Where they can’t simply be removed, they are turned into part-time contracts.

- The money has to be used in polishing the data: A department was recruiting a lecturer. Having completed the recruitment exercise and found the right candidate, the nomination was rejected by the faculty board, who said: why aren’t you hiring a professor if you have the money?

- What happens when you can’t offer enough courses? A professor’s salary is easily 2-3 times of that of a lecturer, but since they have to focus on research, their teaching load may be only half or just 1/3 of that of a lecturer. So what happens when there are not enough courses? That is why we often hear students complain about a lack of course choices. Sometimes even core courses are at risk.

Fragmentation of funding, casualisation of teaching

Our former president Emily Ng wrote two articles in the local press last month, pointing out that since 2004, the UGC has broken down the original resources into numerous earmarked short-term funding schemes [ 2]. With much hard work a professor manages to secure a grant. Now they need time to conduct the research, so these schemes cover teaching relief that allows departments to hire substitute teachers for a course or two. The more of these research schemes, the more short-time and part-time teachers there are. This is the adverse effect of UGC’s funding policies. For administrative/financial flexibility, some departments would also turn regular full-time teaching posts into part-time posts. All these are reasons why teaching jobs are so casualised today.

How much is moral responsibility worth?

Talking about precarious work, we surely should not forget about the teachers

on short-term contract of 1–2 years. These constitute almost 60% of all

teaching staff. We recently saw several scandals in sister universities

where whole lots of contract teaching-track staff were laid off. In our

university too we have seen popular teachers not being able to renew their

contracts.

The double-cohort in 2012 meant there was a surge in the demand of teachers.

The cheap labour of lecturers and part-time lecturers was a great help.

Now that the new curriculum is in full implementation, these colleagues

continue to play an important role. They allow professorial track colleagues

to focus on their research to compete for funding and ranking. At the same

time, their presence helps maintain faculty-student ratio and teaching

quality. (The ratio is one of the few measurables for teaching in international

rankings.) But now that departments are facing deficits, they are the first

to be sacrificed. How much is moral responsibility worth?

Teachers adrift, students suffer. University reputation itself is at risk.

The far-from-ideal working conditions of part-time teachers translate

directly into negative impact on student learning. (More in the accompanying

article.) These colleagues are paid by the contact hours. Even when these

have taken into account preparation and grading time, but what about tutelage

outside class? Both members interviewed in this issue pointed out the importance

of student-teacher relationship in university education. Under the current

policy where research weighs more than teaching, professors are forced

to produce papers behind their shut doors, whereas part-time teachers simply

do not work in conditions that allow them to have deep understanding of

their students. Not to mention that it is not easy for students to find

someone to consult after class, it is now even difficult for them to find

a teacher who knows them enough to write a recommendation. We all know

that our students have been under a lot of stress in recent years. We have

seen our students giving up their own lives.

While the reasons behind may be varied, if they had had a closer relationship

with their teachers, perhaps the problems could have been identified earlier

and tragedy may have been avoided? Rather than issuing an open-letter after

a tragedy to say how deeply sorrowful and regretful he is, can the Vice-Chancellor

do something real to improve student-teacher relationships?

The sources of the current difficulties and absurd phenomena faced by

the universities are clear: Frist is the UGC’s funding policies; second

is the undemocratic governance and management within the universities.

The first is not just a matter of money. What is more important is a fundamental

change of the current ideology which focus on short-term benefits. The

latter is a result of increase centralisation of power. The Council, Vice-Chancellor

and faculty deans control all the administrative and financial authority.

They make all decisions on resource allocation without any monitoring.

Departments have little autonomy in their development; people with real

learning and genuine aspirations are not given opportunity. As long as

these origins of the problems are not corrected, there can hardly be any

future for our university education.

[1] See in this issue: “UGC’s funding strategies and the budget cut that goes without notice”

[2] 吳曉真:〈算大學教資會的帳〉,《明報》,2018年5月3日;〈再算大學教資會的帳〉,《明報》,2018年5月17日。