Reporters: Edith Liu and Rebecca Wong

The best money saving advice may not come from financial planners, but from the 290,000 elderly people who are now living in poverty in Hong Kong.

They sit idly in the park, leaving their home appliances switched off to avoid steep electricity bills. They visit the markets at sunset when the food is the cheapest and unsold meat is occasionally given away for free. They do not cook very often because a simple dish can be stretched to feed them for at least three days.

The elderly save in every possible way. They save because they have to.

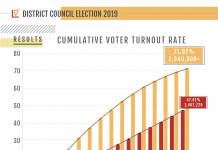

The elderly poor population has increased by 14.2 per cent over the last decade, according to the Hong Kong Council of Social Service (HKCSS). Between 2009 and the first half of this year, the elderly poverty rate rose from 31 per cent to 34 per cent, the biggest increase among all the age groups. It means one out of three Hong Kong residents aged 65 or above is now living in poverty.

The HKCSS draws the poverty line at half the median monthly household income using the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development definition. In the first half of 2010, a single-member family with a monthly income below $3,275 would be regarded as poor, while for a three-member family, the poverty line is drawn at $10,000.

Traditionally, the elderly got by on money given by younger family members and their own savings. The government provides a supplementary benefit in the form of Old Age Allowance, also known as “fruit money”.

However, the elderly can no longer rely on the financial support of the younger generation. With the change in emphasis from the extended family to nuclear families, and the proliferation of the working poor population, it is no longer a given that sons and daughters are able or willing to support their ageing parents.

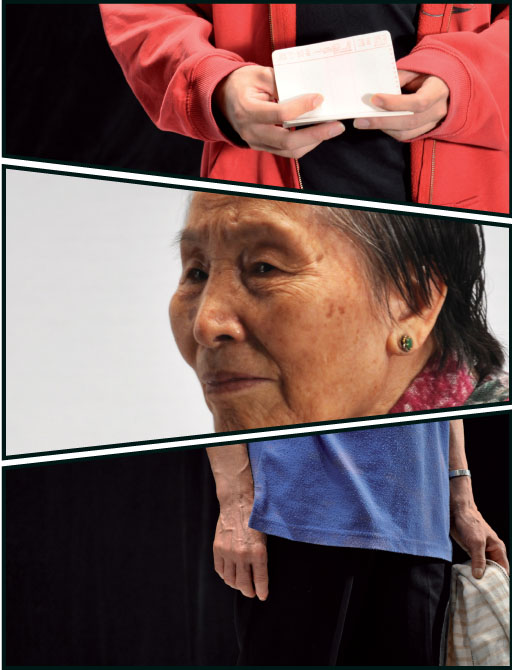

Ms Yeung, 82, lives with her son, his wife and their child in Diamond Hill. It is a working poor household and she does not expect her son to take care of her financially. “He has only given me around $3,000 in the past few decades,”says Yeung.

According to Mariana Chan Waiyong, the chief officer of the Policy Research and Advocacy of the HKCSS, the dependency ratio for working poor households like Yeung’s is higher than that for better off families.

Studies show that on average, each worker in a working poor household has to support two family members in addition to himself or herself. That is more than double the dependency ratio for the population as a whole. “We can hardly rely on the working poor to support the elderly,” Chan concludes.

Like many people in her generation, Yeung had little in personal savings to begin with. She used to work day and night as a tailor in Macau, but she could only afford to live in a squatter hut on her meagre income. “How could I save a penny?” says Yeung. “I didn’t even have enough to feed myself!”

She is now depending on the monthly Old Age Allowance of $1,000. This is her only income so she has to be frugal; she has to buy food for herself during the day and on weekends when her daughter-in-law cannot prepare the family meals. She is also responsible for all her medical and miscellaneous expenses.

The fact that the elderly cannot rely on their children or savings means they have to survive on social assistance, their wits and their own bare hands. Ms Ho, 70, supports herself by collecting used cardboard and aluminium cans on the streets that she can sell to recyclers.

“I try to collect more so that I can buy more vegetables,” she says.

Life as a waste-collector is hard, the buyers keep offering lower prices and she is in no position to bargain. “It has always been like this: no talk!” Ho exclaims as she describes a recent experience, when her 2 kilogram collection was valued at 1 kilogram.

Some elderly people try to find work, but age is a problem when it comes to employment. Tam Kit is ashamed of relying on his 59-year-old wife and wants to fend for himself. He has applied for jobs, but nobody will hire him at the age of 75.

“I read in the newspapers that delivery men are wanted. It says there is ‘no age limit’, but people will not use you in the end,” Tam sighs.

The elderly find they are excluded from socio-economic activities. As their physical capabilities deteriorate, so do their work opportunities. “Therefore they are more likely to fall into the poverty net,” says Professor Wong Chackkie from the Chinese University of Hong Kong Social Work Department.

As working is not really an option for most elderly people, social welfare is their only means of survival. Under the Old Age Allowance, individuals aged 65 or older can get a monthly $1,000 payment from the government, provided they have resided in Hong Kong for 60 days a year. The elderly can also apply for means-tested Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) payments.

For the Tse’s, the payments are hardly adequate for leading a secure and dignified life. Mr Tse is 74 and his wife is 75. They each get the Old Age Allowance and monthly CSSA payments of $2,000.

They live on the seventh floor of an old public housing estate in Shek Kip Mei with no elevators. The couple’s home is cramped and dark. Worn-out clothes and old newspapers are everywhere. The beds are so small that there is hardly enough room to turn over in them. There are no large electrical appliances, just a fan, a television set and a small cooker. The walls show signs of water leakage.

Mr Tse says they economise by eating less and worse. “At every meal, each of us can only eat two pieces from each dish. Just two pieces, we don’t eat any more than that.”

He used to go to markets in Sham Shui Po where cheap food can be found very early in the mornings. “Though in such a dark environment, you often don’t know whether the food is fresh or not,” Tse jokes.

Seeing how the government is prepared to spend lavishly when it comes to bidding to host the Asian Games, Tse complains that the suffering of the deprived is not due to a scarcity of social resources, rather the government is shirking its obligations. He strongly urges the administration to raise the amount of the Old Age Allowance.

Although the elderly can scrimp and calculate every aspect of their expenditure, they cannot avoid medical expenses, both expected and unforeseen. The government offers public medical services at $45, and charges an extra $10 for each drug. Each elderly person is also given a medical voucher of $250 each year. However, many are terrified of falling ill.

Mrs Tse had a stroke early in the year. With no money for additional medication, she only takes $10 medication for blood pressure and inflammation offered by the public hospital. “As a poor person, you must hope you don’t get cancer,” says her husband. “Cancer patients have to take expensive treatments.”

Connie Ng Man-yin, the service manager of the People’s Food Bank of St. James Settlement, estimates those with chronic diseases need a minimum income of $5,000 a month. “It is because they have to make frequent trips to see their doctors and get medications. Diabetes patients are especially in need of more money, as they have to buy very expensive testing paper.”

As for the medical voucher, Ms. Lam, 85, blew her one and only medical voucher on a single visit to a private clinic. “One time, then it [the voucher] is gone,” says Lam. The small amount is even insufficient if used in public hospitals. Lam hopes the government can raise the amount to cover her frequent medical expenses.

In the latest Policy Address, the Chief Executive stated that this is currently being considered by the government.

The Society for Community Organisation (SoCo) spokesperson Ng Wai-tung, welcomes the move as better late than never. He suggests $2,000 would be the ideal amount.

For long-term patients, there is the Disability Allowance. However, those who get the $1,280 Disability Allowance will not be given the Old Age Allowance. It means the elderly who are also chronically ill are only entitled to $280 more than their healthy peers.

For elderly people on tight budgets, the $280 really matters. Until this September, 71-year-old Ms. Ho was receiving the Disability Allowance for regular treatments for pain she was suffering following leg surgery. But after her doctor evaluated her condition and decided she was fine, the government replaced her Disability Allowance with the Old Age Allowance.

Ho says she still experiences pain in her legs and feels angry and disappointed about the reduction in her payments. She is now appealing the case.

SoCo’s Ng says the government lacks sincerity when it comes to medical welfare for the elderly. “The government responds quickly to the requests of land developers. But when it comes to elderly poverty, it muddles through its work.” He cites the example of the scrapping of the Commission on Poverty in 2007.

But material assistance is only the first step. Establishing a long-term policy with clear objectives is the key to eradicating elderly poverty. The Mandatory Provident Fund (MPF) System, launched in 2000 will reach maturity by 2030. It should ensure the provision of retirement protection for members of the workforce. But there are still loopholes.

CUHK’s Wong Chak-kie says, “People receiving less than $5,000 a month do not have to pay for their MPF. Their employers pay for it solely. The amount contributed is not enough to support living at today’s standards. How can you expect that there will be enough in the future?” What is more, the MPF does not cover people who are not in paid employment, such as homemakers.

To better protect the quality of life of the elderly, Wong suggests that the multi-tier social security system proposed by the World Bank in the 1990s could be a better alternative.

Hong Kong currently has two of the three pillars recommended in the model, namely a mandatory and private-funded pension scheme, and a voluntary personal money-saving habit. The missing element is a universal pension provided by the government. Wong suggests it could be in the form of social insurance, with productive members of society supporting retired people.

Although it is hard to predict what policies the government may introduce in the future, one thing is sure: the population is aging. Hong Kong’s elderly population will reach 2,061,900 in 2029. According to the HKCSS, on the current course, there will be 842,000 old people living in poverty by 2039.

“The elderly poverty problem will get much worse if something is not done promptly,” says Ng Wai-tung