Younger alumni want a bigger say in school policies

By Joyce Cheng and Sharon Lee

The heavens opened and the rain mingled with the tears rolling down the cheeks of a row of young women in drenched blue cheong sams. Undeterred by the amber rainstorm warning, old girls, students and parents of students of St Stephen’s Girls’ College (SSGC) marched around the historic school’s Mid-Levels campus.

They held up signs and sang the school song to protest against the decision to join the Direct Subsidy Scheme (DSS), which would allow the school to start collecting fees and cherry pick students from outside its geographical school net.

Standing at the front was Joy Liu Shuk-wah, a third-year student at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and an old girl of St Stephen’s. “St Stephen’s across the generations, let us continue our walk, shall we?” proclaimed Liu as the others followed.

The march on July 7 proved to be a turning point in the campaign to stop the school from becoming more selective and illustrated the increasing importance of alumni in influencing school policies.

The alumni movement began to take shape in the campaign against the introduction of a mandatory Moral and National Education (MNE) curriculum last year. In August 2012, the Parents Concern Group on National Education launched a letter campaign encouraging Hong Kongers to write to their respective primary and secondary schools as students, alumni or parents. Of the 5,000 letters that were sent out, 60 per cent were from alumni.

Alumni concern groups sprang up on social media networks and then formed in person to monitor whether and how their schools planned to implement the curriculum, and to oppose such moves.

These groups were very different from the traditional alumni associations found at most schools. These usually offer lifelong membership to any graduates of a school and charge either an annual subscription fee or one-off payment. Association committees organise regular gatherings and activities for members, and are mostly seen as social clubs.

When Tai Lok, a 23-year-old former student of the pro-Beijing Pui Kiu Middle School, formed a national education concern group for the school, he met with disapproval from the school’s official alumni association.

Tai, who is now studying government and political administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, was schooled in the Mainland until he moved to Hong Kong in his early teens. He describes his education as being very pro-establishment.

“It’s hard for secondary students to have their own points of view, they’re usually influenced by their environment. Pui Kiu influenced a lot of the students’ [mindsets],” he says.

Tai recalls the school often invited guest speakers with pro-establishment backgrounds to hold talks and discussions. “The most unforgettable one was Jasper Tsang Yok-sing,” says Tai. “He talked about the shortcomings of democracy. He tried to persuade us that democracy wasn’t always good, that not everyone had to have a vote. It was a big blow to me.”

Tai began to think differently when he was in Form Six and entered a writing competition about China’s 1911 revolution. By the time the national education controversy erupted, he had very different views from his school.

This prompted him to return to his alma mater with some other alumni to hand out leaflets and black ribbons at the school entrance to oppose the subject.

Both the school and the alumni association frowned on their action. The school suppressed the protest and, in a school assembly, told students their seniors had behaved badly.

Tai is not surprised. He says the alumni association is very close to the school management. Its events are not limited to alumni. Instead it helps the school to organise tours to the Legislative Council and holds seminars for current students. “Frankly speaking, our alumni association joins hands with the school at all times. It’s hard to be close to the centre of power in the alumni association unless you identify with the school’s beliefs,” he says.

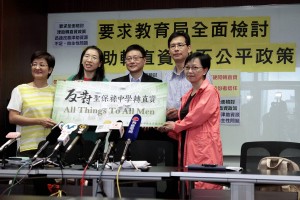

The Maryknoll Fathers’ School (MFS) Alumni Concern Group also has strained relations with that school’s official alumni association. Matters came to a head when around 40 alumni, including four anti-national education activists, had their applications to join the alumni association rejected in October last year.

The association explained this was because the recruitment of new members had been suspended pending changes to the group’s constitution. But two of the affected concern group members, Linda Wong Shui-hung and Rock Li Cheuk-yin are unconvinced. They think the underlying reasons are political.

Wong, 36, says she did not join the alumni association when it was set up in 2005 because she was unsure of what she could contribute to the school at that point. Now she is established in her career as a barrister, she wants to give back to the school.

Wong lauds the past achievements of the alumni association, of which Secretary of Security Lai Tung-kwok is the honorary head, in raising funds for the school’s expansion. But she questions the association’s explanations and notes that unlike the alumni concern group, the alumni association is made up of former students who graduated a long time ago. “A healthy and representative alumni association should encompass voices from different generations,” says Wong.

In contrast, another activist who has been rejected, Rocky Li adopts a less conciliatory tone. He says the application refusals must be related to the anti-national education stance of a few concern group members, while the other alumni whose applications are on ice have just become embroiled in the dispute. Varsity contacted the school for a response but was told the person responsible could not be reached.

Unable to make any headway with the alumni association, Li directly approached the school’s sponsoring body, the Catholic Diocese of Hong Kong. The sponsoring body supervises the school’s Incorporated Management Committee (IMC), which is responsible for school planning, management and formulating education policies.

By going directly to the sponsoring body, Li bypassed the complex hierarchy of the school structure. Unexpectedly, the sponsoring body supported him and even invited him to join the IMC.

Looking back on the long-running dispute, Li says: “I feel like a group of senior successful alumni with high social status are monopolising the MFS Alumni Association.”

If the big education story of summer 2012 was the row over national education, then summer 2013 was marked by the controversy over the decision by some elite government-aided schools to join the Direct Subsidy Scheme (DSS). St. Paul’s Secondary School (SPSS) and St Stephen’s Girls’ College (SSGC) were among the most prominent.

Betty Wah Shan, 33, is a St Paul’s old girl and the spokesperson of the Anti-DSS Concern Group (SPSS). After SPSS applied to join the DSS last December, alumni who had been active in the anti-national education campaign met up again and formed the concern group against DSS.

Although she was not previously a member of the alumni association, Wah says she now wants to join and reform its role. “Alumni associations used to act like a social club, holding farewell functions and raising funds. But after national education, I think alumni associations should have a different role; there should be more voices within the associations to deal with different issues,” says Wah.

Wah says the youngest committee members in the SPSS alumni association are graduates from the years 2004 to 2006. In comparison, the anti-DSS concern group members include younger graduates, who only left the school three to four years ago. She anticipates the younger generation will volunteer to join the alumni association and bring fresh perspectives.

Much like the alumni campaigns against national education, the alumni-led anti-DSS movements have brought different generations together in their concern for their alma maters.

For university student and St Stephen’s Girls’ College alumna Joy Liu, the experience has been an eye-opener. For Liu, the school’s sudden decision to join the Direct Subsidy Scheme violated its core value, which is to provide an excellent education to girls of all backgrounds.

When Liu attended the consultation session for alumni on the DSS issue, she met the senior alumni from her school for the first time. She was touched that, regardless of age, many upheld the same principles as her. They swapped contacts and attended the subsequent consultation sessions.

Once the concern group was formed, it was able to fully utilise the respective strengths of alumni from different generations. The post-80s and post-90s were skilled in using social media for publicity, and designing posters and online graphics, while older alumni had powerful connections and valuable experience. “Their life experiences are much broader than ours. They have the personnel resources, the capital and careful planning skills which help to direct us to deal with the press. Both generations learn from the other during the process,” Liu says.

Not being under the same kind of social and professional pressures as the older alumni, Liu and the other post-90s members could speak out boldly on behalf of the concern group. “We have nothing to lose at all,” Liu says.

But Liu adds that, despite the generation gap among members of the group, they are of one mind. “We have something in common, that is a passion for our alma mater. Otherwise, we would not have devoted so much time and effort to this DSS issue.”

Not many members of the concern group belong to the official alumni association but that should not detract from their status or identity as old girls of the school, says Liu. She believes every alumnus should inherit the distinct spirit of their alma mater and that there should be a natural bond between former students.

The efforts of Wah, Liu and their fellow alumni finally paid off. Under tremendous pressure exerted by their alumni and the general public, both SPSS and SPGC scrapped plans to become direct subsidy schools.

Liu now wants to join the St Stephen’s alumni association. In the past, she was unaware that the association had voting rights in forming school policies. “Every single vote counts to make a change,” she says.

The campaign against national education did not just inspire young people to participate in social movements, it also motivated people from different generations to reconnect with and take a keener interest in their old schools. The active participation of younger alumni could bring lasting changes to the composition and role of alumni associations.

Edited by Nicole Chan