Meet the collectors who want to preserve our history

By Emily Man

The reading on the thermo-hydrometer on a custom-made cabinet shows the humidity within is below 60 per cent. Tam Kwong-lim opens the cabinet doors and carefully takes a scroll out from a long wooden box. He unfurls it to reveal an antique map of the coastal region of Southern China. On the map, the place where Hong Kong should be is marked as “Hung Heung Lo” (Red Incense Burner).

The map dates back to the 19th century and the late Qing dynasty. Tam explains that Hong Kong harbour was an important water channel at that time so the Qing government needed to set up a military station on the unnamed island and later decided to formally name it as Hung Heung Lo after the Hung Heung Lo Tin Hau temple. Not until the arrival of the British in the early 19th century was the island renamed “Hong Kong”.

Having studied geography at the University of Hong Kong and worked in the shipping industry, Tam’s life has been intertwined with maps. He was first drawn to them during his secondary school geography lessons, in which he had the opportunity to study maps of Britain. He was fascinated by these colourful maps, and enjoyed examining the British map legends to find out where the villages, roads and other features were. “At that time, I had much imagination about those splendid places which Hong Kong did not have,” he says.

But it was his stay in Japan for work that sparked his lifelong passion for map collecting. In the Kanda district of Tokyo, he came across quite a number of antiquarian bookshops which also sold old maps, such as those from the Second Sino-Japanese War. He became intrigued by them, and later started collecting antique maps of different countries, like China.

So far, Tam has collected more than 2,000 maps including his favourite one which is now publicly exhibited in the Hong Kong Maritime Museum. It is a hand copied version of the six-page Great Universal Geographic Map drawn by the 16th century Jesuit missionary and explorer Matteo Ricci.

When Ricci arrived in China in the late Ming Dynasty, he showed the western version of the world map to the Chinese people. “They [the Chinese] had believed that the world was China,” says Tam, “and they had thought the earth was flat.” The news of the world map quickly spread to the Chinese Emperor, Wanli, who then requested that Ricci combine Western maps and Chinese maps into a real world map – the Great Universal Geographic Map.

Copies of the map became popular in Japan, and as the Japanese did not know the wood board printing technique, each copy there was hand-drawn. There are now 21 such copies of the map in existence in the world, one of which is Tam’s – each with an estimated auction price of US$150,000 to US$250,000. But for Tam, the maps’ value lies not in how much money they are worth but in their historical significance.

Maps are not the only artifacts that provide us with a window into the past. William Tong Cheuk-man, the 58-year-old president of the Hong Kong Collectors Society, is fascinated by the history represented in his collections. Tong says his love of history only really blossomed after he began collecting.

To let the public know more about the geography, history and maritime heritage of Hong Kong, Tam will consider loaning more maps from his collections to the Maritime Museum in the future upon request.

Maps are not the only artifacts that provide us with a window into the past. William Tong Cheuk-man, the 58-year-old president of the Hong Kong Collectors Society is fascinated by the history represented in his collections. Tong says his love of history only really blossomed after he began collecting.

“You need first-hand data to study history,” Tong says. Among the original objects in Tong’s collections are old photos, postcards, documents and other paper artifacts. But the ones he likes the most are old revenue stamps. He has already collected more than 5,000 types – some are just the stamps themselves, while others are attached to legal documents.

Tong treasures revenue stamps not just for their beauty but also because they depict life in the past. He explains that in the past, people needed to pay stamp duty on almost every document – from land leases to graduation certificates, and even the documents people drew up when they sold their children, their maids or their wives due to financial difficulties. “Because these are transactions, [for] the legal effect, they must stick on a revenue stamp,” says Tong.

Tong stores his collection in the 1,000 square foot storeroom he owns in an industrial building in Kwun Tong, and he estimates he has spent “several millions” of dollars on his collections.

But even an enthusiast like Tong has his limits. He will not indulge himself by spending too much on his hobby. Tong recalls that thirty-something years ago, someone wanted to sell him a rare revenue stamp bearing the words “Chinese Empire”. The stamp hailed from Yuan Shikai’s short-lived Hongxian Dynasty which lasted for just four months between 1915 and 1916. But he thought the price tag of more than HK$20,000 was too high, so he did not buy it. He says it would be even harder to do so now as its value has increased more than tenfold. “Never mind, never mind, sometimes [I] don’t need to have all these things,” he says.

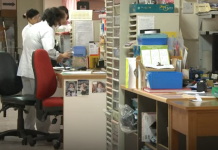

Collecting artifacts can be an expensive hobby, and the work of conserving and preserving them is also costly. Lai Chun Ying, a 64-year-old conservation professional says that it can take up to a month, and HK$40,000, to conserve one antiquarian book. Lai works as a conservation specialist for the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals and is responsible for conserving the group’s historical documents. These include the only set of medical records from 1911 to 1945, which survived both world wars, in Kwong Wah Hospital, as well as the archive in Tung Wah Coffin Home.

These historical documents are in a fragile state – having been stored in a humid and dark room for years, most of the records were either stained and damaged by mould, or attacked and eaten by insects, some of the pages could not be turned.

Preserving these valuable historical records requires meticulous care. Most of them are bound with red thread that is loose and unstable. Lai and his colleagues conduct tests on the threads every five years to ascertain their condition. One of the tests showed the red threads contained the molecule Br4, which is highly water soluble.

This complicates the conservation procedure. As the threads cannot come into contact with water, the conservators cannot apply liquid glue to the threads, instead they must spread the glue on the pages and use blotting paper to absorb the excess water on the pages. When the page has partially dried, they quickly cover it and flatten it.

This task alone is time-consuming enough, yet it is merely one of the many tasks a book conservator has to carry out. Lai says the job of conserving just the documents at the Tung Wah Coffin Home takes up a lot of his time. “Even with a long time, [I] still cannot finish it. It takes at least 10 years,” he says.

As a teenager, Lai studied at the Tang King Po School, a catholic vocational school which offered printing, shoemaking and tailoring classes at that time. Among these three, Lai was most interested in the printing industry, which was undergoing a boom time in the 1960s. Given his interest and with an eye on making a living, Lai chose to enter the printing class. Not only did the fathers in the school teach him techniques such as typesetting, printing and binding, but they also taught him how to repair missals. This became the foundation of his life-time work in book and document conservation. However, from 1995, his main focus shifted from Western-style thread-stitched books to Chinese-style thread-bound books.

Though he first entered the industry for mainly pragmatic reasons, his enthusiasm for and gratification from book conservation has grown steadily over the years. His devotion to his craft is heightened by the lack of successors. “Not many people are able to do this if I step down,” Lai says.

Today’s news is tomorrow’s history and while it is important to conserve the past, it is equally essential to preserve the present for the future. And, archives serve this function.

Although the concept of archive is lesser-known and some people mistake archives for museums, they serve an important function as repositories of the historical record. Yip Chun-man, Archives Manager at Manulife (International) Limited and a member of the Hong Kong Archive Society, says archiving is about keeping records rather than collecting artifacts. He gives an example of a watch. A museum may add the watch to their collection depending on its value whereas archivists would collect business records including the design of the watch and the purchasing orders for the parts.

“Those [watches] tell the story, but placing it in context is down to different types of documents. Only if the documents are well preserved can the display [watches] have substance.”

Within an organisation like Manulife, an archive is a collection of records created or received and are the evidence of business transactions.

But they can also document and record the history of governments, academic institutions, various communities and even individuals. “It also keeps track of a historical incident…this is the history of the organisation,” says Sarah Tam, treasurer and membership secretary of the Hong Kong Archives Society.

Sarah Tam thinks the ordinary documents of individuals, like bills and bank statements, can also reflect the social situations in any specific time and space. For example, receipts from the 1970s show that one catty of rice only cost about HK$3 at that time but now the price has more than tripled to over HK$10 for one catty. “Documentation is important and is not really far away from us,” Tam says.

However, she notes that archives are not common in Hong Kong. As there is no archives law in Hong Kong, private organisations do not have any general guidelines to follow to preserve their historical documents. But she thinks more organisations have started paying attention to archives in recent years, and she is positive about the development of archives in Hong Kong.

“History after all needs to be preserved. If not, when you do research in future, what will you get? You will have nothing to see, and this is not okay,” Sarah Tam says.

Edited by Grace Cheung