Lego has captivated generations of children but do contemporary sets stifle creativity?

By Kelly Wong

It has been around since 1949 and still continues to bring hours of fun to children around the world. Some may slavishly follow instructions to build a pirate ship, or a spaceship or a a rather angular tree. Others may simply let their imaginations take over and build whatever comes to mind. But whatever they create, their raw material is the same Lego – that deceptively simple system of hollow interlocking plastic bricks that can be put together to form infinite combinations, and then be taken apart so you can start all over again.

Jared Chan Chun-kit, the Facebook editor of LegendBricks, a Lego user group founded in 2010, takes two flat pieces with rounded ends and quickly makes them into a heart. He takes two plastic bow-and-arrow pieces and turns them into the armrests of a chair.

“Sometimes it’s really a test of if you can think of [the construction] or not,” Chan says. “ If you’re as crazy about it as we are, then play it as frequently as we do, the power of observation is very important.”

It is precisely because playing with Lego can inspire this use of imagination, creativity and observation that the toy has been a firm favourite with not just children but also their parents and teachers. The toys are used in the classroom and some schools even offer after-school classes in Lego building.

But in recent years, Lego has come under criticism for becoming less creative and for reinforcing gender stereotypes by bringing out “themed” sets based on blockbuster films like Star Wars and Pirates of the Caribbean and sets targeted specifically at girls. These sets include instructions for pieces that are specially designed to make specific objects.

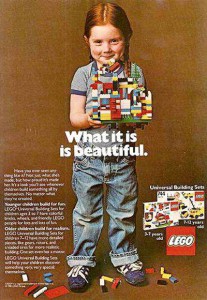

Critics were quick to point to Lego’s own advertisements from the past, including one from 1981 featuring a little girl wearing a blue T-shirt and jeans and proudly holding up her Lego creation, which highlighted a very different ethos. Lego was less theme oriented then, and consciously gender neutral. Along with the slogan “What it is is beautiful”, the copy reads “Have you seen anything like it? Not just what she’s made but how proud it’s made her. It’s a look you’ll see whenever children build something all by themselves. No matter what they’ve created.”

Sadly, this is not an experience that Alex Tam Shun-yiu, who is a committee member of Hong Kong Gifted Family Association, can share from his own experience with Lego.

Tam recalls that he did not find playing with Lego appealing at all. He was not capable of following the instruction booklet strictly to assemble the bricks. He ended up frustrated and finding things to blame.

He argues that assembling the bricks with the given theme–setting and guidelines does not reveal people’s creativity.

“Not only does Lego fail to show how creative I am, but it also hinders my creativity. If the Lego is based on a theme, then you can only follow their instructions to build a ship or a building as your final products,” he says.

But for Jared Chan, real Lego lovers can build with creativity regardless of the sets, even if they are themed, all it takes is practice and experimentation. Chan uses the example of building Lego trains. Since the company has produced different types of parts over the years, Chan tested his skills by building three versions for the same train using different types of parts. “This is a task to challenge myself, to keep thinking whether new parts can fit in my train and to make it look better,” Chan says, “ This is exactly what creativity means.”

According to Chan’s reasoning, even with very specific pieces designed for specific sets, children can still bring their talent in creativity into full play as long as they are encouraged to do so and do not feel compelled to follow the in-box instructions. For this to happen, parental attitude is very important.

Ambrose Leung Shing-yin’s five-year-old son Andre attends classes at BrickArt Design Studio which sells Lego creations and customised products. But he allows Andre to play with Lego without instruction and guidance.

Leung says he wants his son to explore and find his personality through playing with Lego. Instead of obeying orders and rules, his son can live up to his potential and pursue his dreams in the future.

“We should not guide the children. Like, if my son tells me he wants to build a Lego building that is taller than the ICC (International Commerce Centre), I tell him to think about how to achieve that rather than saying it is impossible,” Leung adds.

To inspire his interest in Lego, he does not limit his son to buy gender-specific lines, for instance, City which is targeted specially at boys. Sets in the line include construction sites, police units and race-cars. Leung chooses the Lego Architecture series instead which better suit his son’s interests.

Criticism of the company for gender stereotyping children’s toys is comparitivley recent. The Danish firm was heavily criticised for Lego Friends, a range aimed at girls launched in 2010. The pink and purple themed sets– which feature a group of five friends who seem to lead a life of leisure – were criticised for going against the gender equality the company had previously championed.

When an open letter to parents from the company in 1974 was posted on the internet last year, it quickly went viral.

In the letter, Lego states that: “The urge to create is equally strong in all children. Boys and Girls. It’s imagination that counts…The most important thing is to put the right material in their hands and let them create whatever appeals to them.”

Writer So Mei-chi agrees with these sentiments. So says she seldom buys Lego for her son and daughter but they are given sets as gifts or hand-me-downs. When they play with them, So says she does not set any rules or convey gender-specific expectations to them. “Boys can use the bricks to make dolls while girls can build aircraft,” she says. “ I do not think it is necessary to set limits for them.”

However, some parents do have reservations when buying Lego for their children that is targeted at the other sex. Amie Yau Kwong-fan has a six year-old daughter and also a two-year-old son who play with Lego. Although Kwong does not think it is a toy that belongs to either boys or girls, she finds it hard to overcome traditional views. She says that when buying the construction toys for her son, she usually prefers sets like cars which are considered to be boys’ toys.

Hardcore Lego aficionados tend to think the debate over gender stereotyping is overblown. William Wong Hung-hei, a core-member of LegendBricks, believes that neither the gender stereotype issue nor the movie tie-in and themed sets is a big deal. He says players can modify the bricks in the set-themed lines to produce something creative, for instance by building Iron Man’s house on top of a cliff made of Lego bricks.

Wong also sees Lego Friends as a sales strategy to attract more female consumers. He adds that the accessories in the range are useful and cannot be found in previous lines. One of his friends used the pink and purple bricks in Lego Friends to construct a beautiful big wheel. “It depends on how you use and interpret [the bricks in Lego Friends],” says Wong.

Wong’s view is shared by Ray Kwan Yiu-wai, the founder of Brick Art Design Studio. He says the controversial line entices more girls to play with Lego while boys are willing to make use of the pink and purple bricks to enrich their creations.

Kwan says children find the bricks by themselves to be dull while the licensed products with themed settings arouse their interest. That in turn can spur them on to think about how to use the building blocks in alternative ways.

“They will find out that following the instructions is not enjoyable …then [they] will throw away the instruction booklet and create something more entertaining,” Wong says.

Educational psychologist Helen Ku-Yu Siu-yin, the Secretary for the Division of Educational Psychology of The Hong Kong Psychological Society ,says any problems with gender-stereotyped or themed sets are not so much in the toys themselves but in how they are used.

She encourages parents to look at whether they are choosing too many gender-specific toys for their children overall, and to resist the urge to say “No!” when children use their imagination when playing with the bricks.

Ku-Yu says if children are only encouraged to follow the Lego instructions, their imagination will be inhibited and the activity will not help to foster original thinking and creativity.

“That would mean it [Lego toys] only trains a technician, but not an engineer,” Ku-Yu says.

Edited by Agnes Ng

Hi Inter-varsity Editor

Thank you for writing the interesting story on LEGO. If possible, please revise my title listed on page 3, as follows:

Educational Psychologist Helen Siu Yin KU-YU, is currently elected as the Secretary for the Division of Educational Psychology of The Hong Kong Psychological Society …..

This request is made by The Hong Kong Psychological Society香港心理學會 which actually recommended Helen for the interview with your reporters.

Look forward to reading your online amendment!

Helen Siu Yin KU-YU