Calligraphy is gaining new followers as people rediscover the art of handwriting

By Kate Kim

Words and letters are all around us in our daily lives. We may wake up and check our text messages before breakfast, we type documents at work and we might browse Instagram before going to bed. Gradually, it seems touch screens and computer keyboards have replaced pen and paper, and we hardly ever write the old-fashioned way. But recently people have begun to rediscover the pleasures and uniqueness of handwriting.

“Calligraphy has more feeling than the digital texts. It’s more of a human touch,” says Brenda Ching Man-wah, who chairs a local calligraphy lovers’ group, the Alpha-Beta Club. Ching has been giving regular Western calligraphy lessons at the club and this year, she had to turn students away. Time and space constraints mean she could only enroll 12 students out of the 40 to 50 applicants who applied.

“I think [for] people who would like to learn calligraphy, maybe it is quite interesting for them, [and] they want to try something new, something nice,” says Ching. “The computer is too common for them. They would like to make something personal, in their style.”

Ching was introduced to calligraphy by her English teacher in secondary school, and she has devoted herself to the art for years. Currently working as a school teacher herself, she spends her spare time promoting the art of Western calligraphy in Hong Kong at workshops and exhibitions.

In her workshop, Ching teaches students four fundamental scripts, foundational, italic, Gothic, and copperplate. These are what she calls the “basic things” of calligraphy.

Though people learn the same scripts and use the same tools to write, Ching says calligraphy can be very personal. For example, different writers express different feelings by using different scripts. If they want to convey elegance, they can use copperplate flourishes and slanted italic lines.

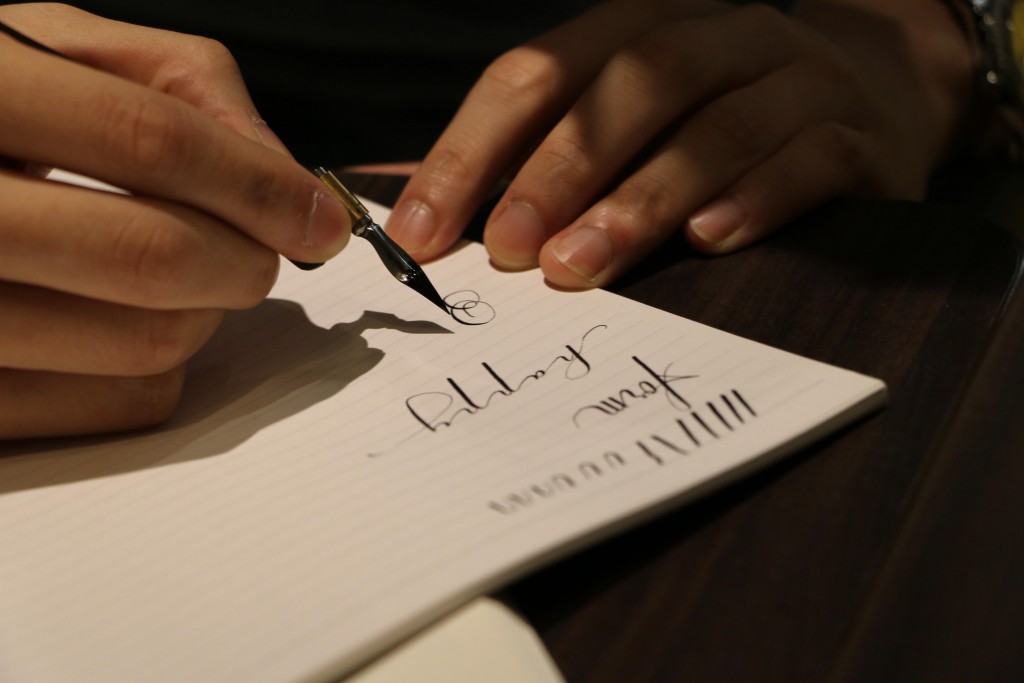

As for tools, calligraphers can choose the typical aluminum dip-pen, with a nib inserted at the end, or they can create their own pen using different materials. Ching once asked a hawker to give her some feathers so she could make her own quill pens.

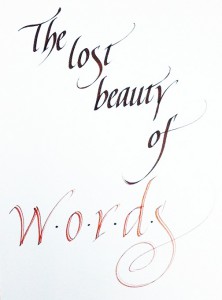

Calligraphy can be very personal

(From Left to right: Jeff Lo Lok-chung’s work and Brenda Ching Man-wah’s work)

However, Ching says that while more people seem to be keen on taking up calligraphy, they seem to be happy with learning the basics and do not really want to develop their skills further. She says she can see this in how her students learn to write the letter “O”.

“It’s quite hard for them, beginners I mean, to maintain the shape of that letter or the speed or the spacing of the letters. It needs time to do so,” says Ching. “But when they find ‘it is fine, it is okay for me, and I can stop practising’, then they think it’s enough for them. But actually, we don’t feel satisfied with them.”

Calligraphy requires perseverance and a neat hand – and plenty of practice. It is unusual for Ching to come across a new student like Tammy Chan, who is not only a fashion merchandiser, but also a calligraphy enthusiast who spends at least an hour a day, five days a week, practising her writing.

In November last year, Chan came across samples of calligraphy on social media and it was love at first sight when she saw the flourishes of copperplate script. After practising on her own, she discovered she had no clue how to write it properly, so she enrolled on the Western calligraphy class. Now, she shares her pieces on Instagram like many fellow calligraphy lovers.

“Somehow there’s a magic in it, some attraction in it. You just want to learn more. In copperplate you can put art in it, make flourishes. And you have to create that on your own. It’s pretty,” she says as she eagerly leans forward to show her calligraphic works.

Chan thinks the way people spend their free time in Hong Kong tends to be rather routine and, overall, they always seem to be in a rush and hardly ever relax. This may be why many people have been turning to handicrafts and DIY (do-it-yourself) activities. Practising calligraphy is a fun and interesting thing to do but Chan observes that many people will just try it once. They seldom want to persevere with the activity as a long-term hobby or art to be mastered and don’t take the writing process seriously.

For Chan, the dearth of people in Hong Kong willing to devote time and energy to calligraphy makes it a lonely art to practise. Unlike painting, singing or dancing, it is hard to find someone with whom to share an interest in calligraphy in daily life. So she wants to remind people of the beauty of calligraphy by practising harder herself.

“So I thought somehow, it [the lack of appreciation] motivated me to practise more, so I might be able to start to teach when Brenda is not free and when Brenda asks me to do so.”

The word calligraphy comes from two Greek words “kallos” and “graphein”, which together mean “beautiful writing”. Western calligraphy, as we know it, developed from the Latin alphabet which first appeared in Rome in around 600 B.C..

In ancient times, before the advent of the printing press, important documents and texts were written by scribes who were trained in the art of calligraphy However, despite the history and tradition of decorative penmanship, its daily application nowadays is limited. “It’s a dying art, whereas Chinese calligraphy is very much alive,” says Keith Tam, an associate professor in the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication at the University of Reading in Britain.

Tam is afraid the difficulty in preserving Western calligraphy could make it a lost art too.

He points out there are some common misconceptions about calligraphy. For instance, people often mix it up with typography. Typography refers to the style and arrangement of typeset letters that can be mass produced, usually through mechanised printing. Calligraphy on the other hand, is about “writing” in a reflective moment and movement.

“There are typefaces that try to mimic the spontaneity of calligraphy but still I think they are pre-made forms that are regularised. So I think there’s a difference,” says Tam.

As a calligraphy lover himself, Tam thinks it is important that people are aware of that difference and the fact that calligraphy can influence type design but not the other way around.

But the difficulties Hong Kong’s amateur calligraphers face in practising their craft are not so much people’s misconceptions about calligraphy, as practical matters such as a lack of supplies and venues where they can hold classes and workshops.

As a non-profit-making organisation, the Alpha-Beta club has no budget for promotions or even hosting a website. Cosmo Kwok Chi-fung, a volunteer calligraphy teacher and council member of the club says: “We have to find different venues for each workshop … in the past, we had to book places like the Cultural Center, which costs money.”

The lack of money also makes it hard for the club to share its work with others through exhibitions. Fortunately, this year a gallery has promised to lend the exhibition venue to them for free. However, it may not be so easy to find an exhibition space in the future.

Despite the challenges, those who persist in practising calligraphy find many reasons to continue their hobby. Jeff Lo Lok-chung has been practising Western calligraphy for a year and half. He loves writing postcards in calligraphy.

“It is handwritten by me. It’s not typing,” he says.

“Even if it was ugly, they’ll still find a way to love it because it’s done by unique me,” he smiles.

Lo also believes practising calligraphy helps him overcome personal setbacks. He was in a rowing team during his university days but, due to a sudden illness, he had to give up and subsequently gained weight. He found that having a hobby provided him with mental support. After trying a few different interests, he finally found calligraphy was the best way for him to express his deepest feelings.

Lo can imagine a future life as a calligraphy master. He saw a video about the last 12 Master Penmen in the world. The youngest is a calligrapher in his 40s who became best in his field after 20 years. This “young” master inspires Chung to perfect his art and imagine becoming a master himself.

“Maybe that is my happiness. It’s about the satisfaction when you learn something and aim high, and are eager to do it right.”

Edited by Stella Tsang