How single dads take up the role of both parents

by Grace Cheung and Yan Li

It is still dark when Chan Yung-kun leaves for work as a security guard. He starts his shift at 5:30 a.m. and, an hour and a half later, he calls his 16-year-old son, to wake him up for school. The day is far from over after his 10-hour shift ends. The 64-year-old still has the dinner to cook and the housework to do before he can finally go to sleep in the cramped bedroom of the public housing flat he shares with his son. This has been Chan’s daily routine for almost two years now after his wife died of cancer in 2012.

When his wife was still alive, Chan was a typical Hong Kong husband of his generation. He was the sole breadwinner of the family and did not spend much time on household chores or parenting. It took him half a year to adapt to his new role as a single dad.

“After work, I still need to go to the market and then cook the dinner. I work non-stop till after 10 p.m. Of course it is very tough. My life was totally different when my wife was here, as she’d take care of the cooking. I didn’t have to do anything after work,” says Chan. Yet, Chan has not actively sought help. “It’s fine. I just try to learn the stuff [housework and cooking] myself,” he says.

Long hours and stressful working conditions in Hong Kong make it hard for single fathers to develop an intimate relationship with their children, even if they very much want to. “Since I need to work, I really don’t have much time to communicate with them [the kids],” says Lo King-lam, a single dad living with two sons in Tai Po.

Since Lo’s wife died from gastric cancer in 2006, he has come to realise how tough her life had been. He recalls how she had to take care of the children, the household chores and work full-time. Despite having so much on her plate, she was the one who had a closer relationship with their children.

Lo’s elder son, Lo Wing-on, who is now 23, recalls he usually went shopping and had intimate chats with his mother. Family days were often initiated by her as well. It was only after she had gone that he started to develop a closer relationship with his father.

Lo King-lam is making up for lost time now. Although it is a challenge for him to do the housework, he decided not to hire a domestic helper as he found he would have less communication with his sons when there was somebody else to take care of their needs. Instead, the family moved to the same housing development where his mother lives so she could help with the cooking.

Often, single fathers do not actively seek either practical help or emotional support when they need it. This is a phenomenon observed by Ken, who does not want to disclose his identity to protect the privacy of his two children. Ken suddenly found himself a single dad after his wife left him for one of his best friends. Their daughter was 10 and their son just three at the time.

After the couple divorced in 1999, Ken ran into financial difficulties with just one income, two children to support and a mortgage to pay. Feeling overwhelmed, he tried to kill himself. Luckily, he did not succeed and instead he approached the Caritas Family Service. With the help of social workers, Ken managed to free himself from his suicidal thoughts.

“When a man’s life is falling apart, he tends to hide himself at home and not consider asking for help,” says Ken. “I believe the most important thing is that you know when to seek professional help when you are having problems. I’m fortunate that there were some good social workers around to help me at that difficult period of time.”

Ken also understands from his own experience that, due to their characters and the way they have been brought up, fathers’ concerns tend to be concentrated on the physical needs of their children rather than on their emotional needs and problems. It is hard for them to help children vent their frustrations, express their feelings and relieve their stress.

In 2006, Ken started a group with some single fathers called Prosperous Men’s Club, under the umbrella of Caritas. The group aims to provide a support system for single fathers and promote men’s welfare in society. It holds weekly meetings at the Caritas Family Crisis Support Centre in Kwun Tong.

Although the club is a step forward, Ken says it is limited in what it can do to help single dads. The group can help the men to relieve some of the pressure but it cannot offer them concrete solutions to practical problems. Nor has it managed to draw much public attention to the plight of single fathers. “Our voice is too weak. Many people still have no idea about these men’s counselling and support services, but luckily there are indeed more service groups for men than before,” says Ken.

Lai Wai-lun, supervisor of Caritas Personal Growth Centre for Men, the first local organisation providing social services tailored to men, points out the importance of peer support and says the effectiveness of such group sharing should not be underestimated. He explains that in small groups, men can channel their sadness through tears because they feel more comfortable sharing their experiences with other men.

Lai adds that providing support for fathers is vital to ensure the wellbeing of children as well. He says any changes in the family environment and emotional problems of a father may have a negative impact on children. Sometimes, the psychological state of children is more difficult to handle than that of fathers.

Eric Cheung Tat-ming, a principal lecturer at the Faculty of Law at University of Hong Kong, has had experience of being a single father grappling with the psychological wellbeing of a bereaved child.

Cheung’s wife died in 2007 after battling cancer. Their daughter is now 18 and their son is 16. Cheung enjoys good relations with both his children, but he once found it hard to comfort his son.

“When I first asked him whether he missed mum or not, he would say ‘no’,” Cheung says. “He often appeared to be fine and accepting, but he was actually not.” Cheung’s son did not know how to express his grief, which eventually manifested itself in unexplained health problems such as skin rashes and stomach pain. At one point, the pain was so severe, the boy refused to go to school for two weeks.

As a leading academic and a church-goer, Cheung received extensive support from professionals, such as psychologists and counsellors, and from his church. Yet none of these sources of support could help solve his son’s fundamental problems. “Professional help was of no use to him. What he needed was vast support from family,” says Cheung. “I could only convey a message to him saying that no matter what happened, I would not abandon him and would keep accompanying him.”

Cheung may be atypical in his open attitude towards outside help. “That’s me! I am very willing to accept the help from others,” he says, but he readily concedes that, unlike his wife, he cannot intuitively feel what his son really needs. “The most important thing is not to be afraid of seeking help, because it is normal. You have to accept your limitations.”

Not all men are as open as Cheung, and together with work constraints, the way men are socialised can be an obstacle to their taking up parenting and household responsibilities on their own. They can find it challenging to take up the roles traditionally expected of mothers in a family.

Chan Kam-wah, professor of Applied Social Science at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, has conducted research on single fathers and men’s welfare services. His findings show that society has different perceptions and expectations of gender roles in society which lead to the unequal distribution of housework and childcare in a family, with mothers doing most of the housework while fathers work outside of the home to make money. Therefore, most single fathers are unprepared when they suddenly have to take up a “mother’s role”, due to divorce or the death of their spouse.

Another problem arising from gender stereotypes is that men generally refuse to seek help form others, even when they face great difficulties. As society expect men to be strong and independent, single fathers often choose to push through on their own instead of looking for professional help.

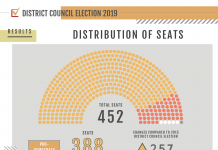

According to the 2011 Population Census Thematic Report, single mothers far outnumbered single fathers throughout the past decade. There are 276 single fathers per 1,000 single mothers (i.e. 27.6 per cent). The total number of single fathers is around 18,000. As there are fewer single fathers, there are fewer services targeting them. This together with gender stereotypes, means the experience of single fatherhood can be a lonely one.

However, Chan does not think there is a disproportionate number of social services targeted at single mothers, as most often mothers are applying for services on behalf of the whole family. Instead of just providing men-specific services, Chan thinks there needs to be a change in the division of responsibilities in families.

For instance, Chan thinks household chores and parenting duties should be shared by both parents and fathers should put more effort into building good relationships with their children. That way, even if they do become single fathers, men will be better able to cope.

Jessie Yu Sau-chu, the chief executive of the Hong Kong Single Parents Association, agrees that traditional gender roles can give men the impression that it is unnecessary for them to improve their parenting or child-raising skills, even after they lose the mothers of their children.

“[For some of them] it’s only after they hit the headlines that they’ll allow people to help them. Sadly, some would rather die with their children than solicit assistance from the service providers,” says Yu.

However, Yu says existing men’s services are inadequate. She says one complaint commonly received from single fathers is they cannot find people in similar situations to talk to. Most single parent support groups in the community are made up of single mothers. In fact, 90 per cent of the cases the association is involved with are single mothers. Yu hopes to organise men’s groups in the association so that they can advise single fathers on how to cultivate father-child relationships and improve problem-solving skills.

Yu says that in general, single mothers may have already have been working mothers who are used to multi-tasking. They may be better equipped to deal with the challenges of single parenthood in that regard. She says these skills can also be learned by men. “Being a single parent is just like a person losing an arm,” says Yu. “What we [the association] can do is limited, but we can help you to see how you can get your remaining arm to function.”

Support from the community and the government is crucial to help single fathers. Yet, as Eric Cheung Tat-ming has pointed out, the most effective support for children comes from within the family itself. While daunting, single fatherhood can also be an eye-opening motivation for fathers to build stronger and closer relationships with their children. As Lo Wing-on, who lost his mother to gastric cancer, says of his father Lo King-lam, “He has done everything he can to keep this family together; he has already given us the best care. What else can we ask for?”

Edited by James Fung