The gap between the young and the old has widened into a chasm since the Umbrella Movement. How can this generational conflict be resolved?

By Megan Leung & Lynette Zhang

“There are so many old people this year, this is the first time I have hated them so much,” wrote one commenter.

“This is the first time I have wanted the elderly in Hong Kong to die. They’re dragging everyone else down,” wrote another.

These comments on September 4, the day of the Legislative Council (Legco) election, were in response to a post on the Facebook page of 100-Most, a youth-oriented satirical magazine and website.

The boundary between generations has always existed, but in Hong Kong in recent years the generation gap has widened into a chasm, especially since the Umbrella Movement in 2014. Two years later, it intensified further as a record number of candidates representing different parties and factions competed in the first Legco election since the movement ended.

The election brought out a record number of voters with a turnout rate of 58.28 per cent. Among all eligible voters, the turnout rate of the 61-and-above age group increased the most – by 23.7% compared to the 2012 Legco election.

While increased participation may indicate more people are taking their civic responsibilities seriously, many youngsters question whether elderly people made informed and conscious decisions when casting their votes. During the election, footage circulated of elderly voters being briefed to vote for a specific candidate before voting and being brought to polling stations in groups.

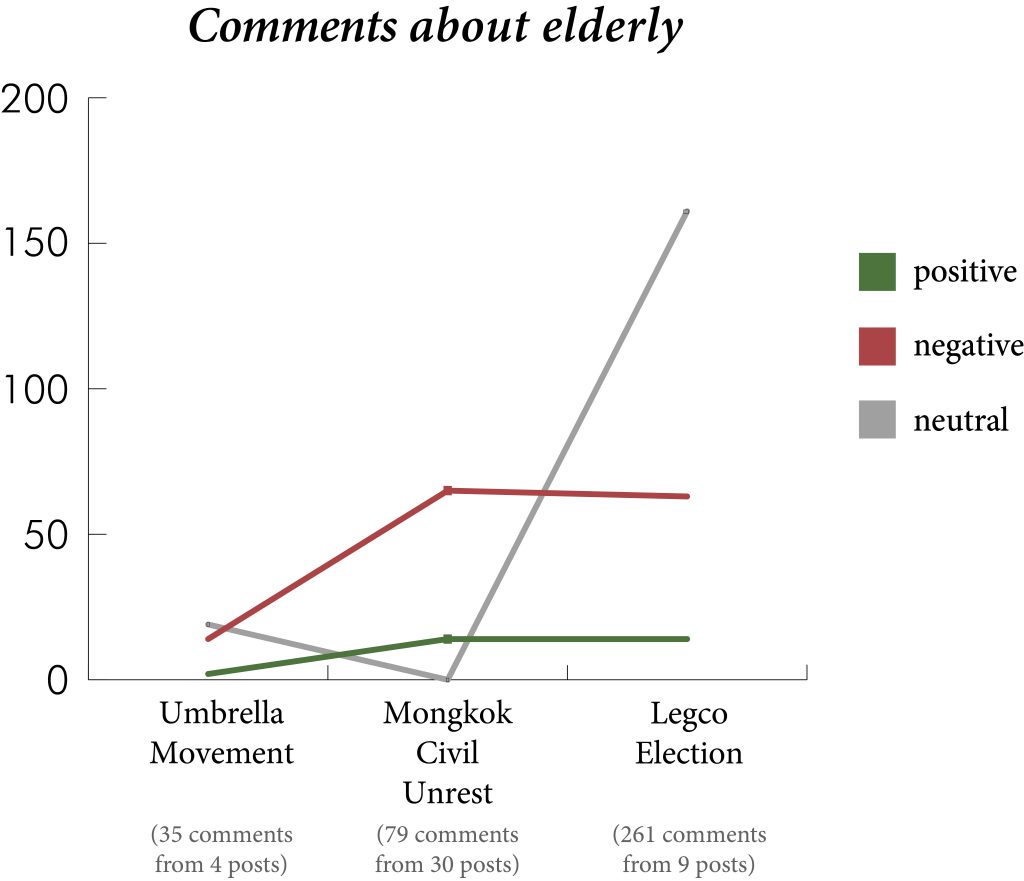

To look at how the younger generation’s opinions about the elderly changed after the Umbrella Movement, Varsity conducted a social media analysis of posts in 100-Most’s Facebook page, since it was established a year before the movement and reflects the views of young people.

We picked three events: The Umbrella Movement, the 2016 Mong Kok civil unrest and the 2016 Legco election. We collected posts and comments over a month, starting from each of the three events and studied the posts and comments about the elderly.

Umbrella Movement: No extremely negative comments, the focus is more on the conflicts between blue ribbons and yellow ribbons. Most of the posts do not talk about the elderly or generational problems.

Mong Kok Civil Unrest: Obvious negative comments appeared, but the wording is not so aggressive.

Legco election: Negative comments appeared which were obvious and extreme, containing words like “fogeys” (老野) “all die” (死嗮) “may you have nothing to depend on in your old age” (祝老無所依) “useless oldies” (廢老廢中) etc., but many neutral comments tend to link the election result to the elderly.

Right after the Legco election, anti-elderly Facebook pages began to appear. Most of these did not gain many followers, but one, “hkelderlymemes”, had more than 36,000 as of the beginning of November.

The “hkelderlymemes” page presents itself as a “just for fun” Facebook page that publishes funny elderly-themed posts. It was set up a day after the Legco election and quickly built up a following.

The posts published tend to be related to news and politics, but they also feature stereotypes and send-ups of the elderly. The page administrators also assume the persona of elderly people to mock their mindset and show how different it is from that of the younger generation.

Granny Lam, 70, resembles one of the typical elderly people targeted by anti-elderly pages. She disagrees with the political views of most youngsters although she rarely discusses it openly, even with her friends.

Every afternoon, she and her neighbours gather on and around benches in the pavilion outside the Wong Tai Sin MTR station, chatting and spending their day together. The neighbourhood has one of the largest elderly populations in Hong Kong.

Granny Lam was born and raised in the area and says she has witnessed how much the district and Hong Kong have changed over the years.

“Your generation has never had a taste of how hard life can be, like in our times. You lot are blessed,” says Lam who thinks the younger generation fails to realise how fortunate they already are.

She also expresses her disappointment with Hong Kong’s political situation in recent years, particularly with the social movements in which many young people took part.

“I have made it clear to my grandchildren that whoever gets into such trouble will have to leave the house,” says Lam. Comfortingly for her, Lam’s three grandchildren all “behave well and make no trouble”. She says a young person’s duty is to get a proper education and contribute to society instead of creating disputes.

Many of Lam’s peers feel the same way about youngsters. Older people use labels such as “useless youth” and “Kong kids” to describe the younger generation as they are considered to be troublemakers who make a mess that society has to clean up afterwards.

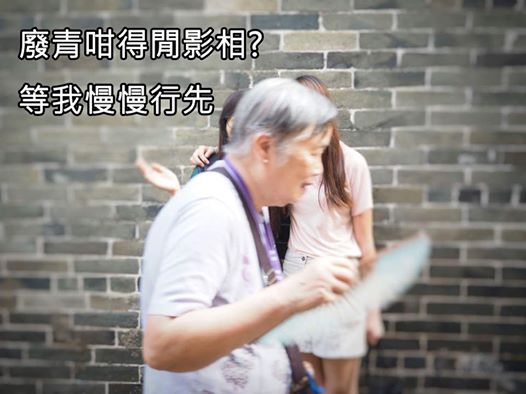

University student Charis Lai Po-wa, 23, is tired of being labelled by older people. She follows hkelderlymemes on Facebook and sometimes shares its posts. Lai says the posts are entertaining and she can relate to them.

Although the posts can sometimes be quite mean, Lai says this does not necessarily mean youngsters who share them would disrespect the elderly in real life. One of the posts she shared features a picture in which an old woman walks in front of a camera while two youngsters are taking a photo. The caption says: “Useless youths even have time to take photos? Let me walk slowly first.” Lai thinks the posts on hkelderlymemes describe common phenomena and resonate with youngsters.

Lai is also an active member of Youngspiration, a political party established in early 2015. She volunteered for Youngspiration’s electoral campaigns during the 2015 District Council election and September’s Legco election. Lai feels strongly about what she sees as the short-sighted elderly who think that what will happen a few decades from now is none of their business.

“They may have made their choice without much consideration, and instead based it on some instant benefits, thereby sacrificing the possibilities of our future,” says Lai. “They underestimated the importance of their vote and the impact it can make.”

Despite the fact that many youngsters treat older people with suspicion, 57-year-old Ng Kam-chuen is still on their side. Although he is middle-aged, Ng considers himself to be young in mindset. An actor in the award-winning film Ten Years, he is also an activist who has participated in social movements in the past. Over the years, Ng has noticed that the disagreements between the generations have become more and more obvious.

As a father of two, Ng understands the hardships youngsters are facing – a society beset with problems, unaffordable housing, an unpromising future and a competitive job market where paltry incomes are not proportional to heavy workloads. Ng says it is understandable young people are dissatisfied with society. Labels like “useless youths” are just sneering remarks made by people of his generation who cannot sympathise with the young. “My generation enjoyed the best and most glorious time of Hong Kong,” he notes.

Still, Ng says there are more open-minded people in society than we think; it is just that many of them are not in the best position to directly voice their opinions. They might not be able to risk the consequences of speaking out because of their jobs or established social circles. Compared to students, older adults have too much to lose, and family responsibilities take precedence over fighting against authority.

As for the boundary between generations, Ng says the different social contexts in which different generations were brought up will always be a hurdle to achieving true understanding. Neither the young nor the old can appreciate each other’s difficulties in life. As a member of the generation in between, Ng does not know how to mediate the relationship either.

Simon Wong, a 72-year-old self-declared non-violent localist, is also known as the youngest of the three Uncle Wong’s in the Umbrella Movement. Wong stayed in the occupied sites throughout the 79-day occupation and also after police cleared the sites in December 2014.

The advances made during the early period of China’s reform and opening up policy (改革開放) gave Wong a positive view of Hong Kong’s handover to China in the 1980s. But the Tiananmen crackdown of 1989 destroyed his hopes and he is extremely disappointed with how things have gone since 1997.

However, he disagrees with the young localists who prefer a more violent approach to protest. He thinks these youngsters lack patience.

“They are not wrong. They’re constrained by their age,” Wong says. “When they’re only 20 years old, five years is a quarter of a lifetime … But for us elderly, five years pass in the bat of an eye.”

Wong has been criticised by other people of his age, but he does not begrudge them. He says the mainstream media present biased stories, which are often the only stories the elderly can read or watch. He adds that some politicians brainwash elderly people by handing out little presents such as mooncakes.

“They [politicians] grab a key point [for those elderly]: a narrow-minded nationalism,” he says. “But Hong Kong accepts a worldwide value. I am one of the Chinese people, but also a citizen in a global village.”

Pang Wei-sum, 48, who is in charge of a community elderly services centre in Sha Tin has a different perspective on what receiving these small gifts means to the elderly. She says that to the elderly, the gifts reflect a concern for their welfare

“They really cherish these little presents. The feeling of being cared for is concrete.”

Pang is surprised by the anti-elderly pages on Facebook. Behind the irony and satire, she thinks the posts are disrespectful and for her, the saddest thing is that the elderly being mocked are exactly those who most need society’s help.

Pang categorises the elderly into two groups: the younger elderly (aged around the 60s to 70s) and older elderly (aged over 80). The younger ones are more educated and tend to have a better social status, since they are still in good health and can help out in households. However, the older ones often feel ignored when their grandchildren grow up.

“You shouldn’t just respect someone because of their economic value. You should also respect them when they are old, alone and weak,” says Pang.

Pang believes the animosity between generations reflects Hong Kong’s polarised society. People are categorising themselves as belonging to different factions and oppose those who hold different views in order to justify their own.

She thinks both the young and the old are labelling each other and discriminating against each other in a self-centred way. This will only lead to more opposition and boundaries.

While it may be unrealistic to expect either side to agree with the other, empathy and understanding are possible. Helen Ng Wun-lam has been taking part in protests since joining the anti-National Education demonstrations in 2012. At 17, she is not yet old enough to vote. But she thought she could fulfil her civic duty by helping out in election campaigns.

Ng remembers a conversation she had with a 70-year-old woman while she was campaigning for localist candidates.

“She told me she was worried that social movements could escalate into war between the people and the government. She had experienced war, and she said it was very bitter,” Ng recalls.

After putting herself in their shoes, Ng says she can see why the elderly wish youngsters could just settle down.

“At their age, after working for most of their lives, you would wish to live a peaceful life for the rest of your years,” she says.

Ultimately, Ng thinks people are selfish – the elderly want a peaceful life and the young want to fight for their ideal future. The important thing is to keep communicating and trying to reach out, she says. After all, the old were once young and today’s young people will be old one day.

Edited by Achlys Xi