Hong Kong’s Gurkha Brigades left in 1997, but the soldiers’ children are returning to make Hong Kong home

Reporter: Yvonne Yeung, Cherry Ge

As Hong Kong prepared for the handover of sovereignty from Britain to China in 1997, a military band played “Sunset” on their bagpipes on a polo field in Sek Kong, Yuen Long.

The date was November 1, 1996 and the men were “beating retreat”, a military ceremony to mark the end of the 48-year presence of the Gurkha brigades in Hong Kong.

It is now 14 years since the territory’s 700 Gurkha servicemen were redeployed but their legacy lives on in Hong Kong’s small but growing Nepali community, and in the annual Trailwalker charity event.

“It will be legendary if we can see Gurkhas competing against the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in the 30th anniversary Oxfam challenge in Hong Kong,” says Danny Thapa. Thapa, now 57, served in the British Army for 20 years, from 1972 to 1992. He was one of the men involved in mapping out the original Trailwalker route.

Trailwalker began in 1981 as a British army training exercise led by the Hong Kong Gurkha Signals Squadron. The exercise raised HK$80,000 to help the Spastics Association of Hong Kong and build a library in a poor Nepalese village.

In 1986, teams of civilians were allowed to take part and Oxfam Hong Kong was brought in to help organize the event. Oxfam Trailwalker has since become one of the largest fundraising sports events in Hong Kong. It is also held in 11 other countries around the world.

An event that tests physical and mental endurance and teamwork, Trailwalker symbolizes the Gurkha spirit.

“Better to die than be a coward” is the motto of the fearsome Nepalese fighters, who became an integral part of the British Army. The name “Gurkha” comes from the hill town of Gorkha, the ancestral hometown of the Nepalese royal family.

Gurkha soldiers fought on the frontline for the British army for 200 years. They participated in the two World Wars, and were assigned to Hong Kong, where their security duties included patrolling the border to prevent the entry of illegal immigrants from the mainland.

After the handover in 1997, the regiment moved to the United Kingdom. Only a few ex-servicemen chose to remain in Hong Kong and make their living here.

Danny Thapa was one of them. After leaving the army in 1992, he got a job as a manager in the manufacturing sector. He says the transition was challenging but not one that he could not overcome. “It takes time to adjust, as we have to face the world as an individual rather than a unit,” he recalls.

Thapa says the Gurkhas who stayed in Hong Kong served in a variety of roles in the military. Most of them were in the infantry but there were also significant numbers of engineers, logisticians and signals specialists.

In the army, Thapa gained knowledge and experience in communications and electronics, which gave him a wider choice of employment in civilian life. “The UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) provided education for related trades and training in the army in order to make sure each serviceman was capable of surviving even after they resign,” he says.

Another former Gurkha, Madan Limbu, who is now a controller in a security company, agrees with Thapa.

But the options for other members of the Nepalese community in Hong Kong, most of whom are the children and grandchildren of ex-soldiers, are more limited.

Although most of the Gurkhas aged 60 or above have chosen to return to their homeland or move to Britain, there has been a trend for younger Nepalese to come back to Hong Kong. The population is still small, around 0.2 percent of the population, mostly concentrated around the Shek Kong and Yau Ma Tei areas where the barracks used to be.

However, government figures show a significant increase in the Nepalese population from 1990 onwards. The increase can be attributed to a policy that children born to Gurkha soldiers in Hong Kong before January 1983 automatically acquired first the right to land and later the right of abode in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong offers better job opportunities than Nepal and many young Nepalese who come here do so in the hope of finding a better job, starting a small business and achieving a better standard of living.

Dewan Padam, a 31-year-old Nepali, was born in Hong Kong but returned to Nepal when he was three. He came back when he was 19 to look for work. Padam is now a successful restaurateur. Like Padam, Ganash Rai is also the son of a former Gurkha. The 23-year-old was also born in Hong Kong but was then sent first to Nepal and then to study in India. He came back to Hong Kong when he was 10. After a succession of jobs, some of them in the food and beverage field, Rai is now a financial consultant.

Both Rai and Padam are satisfied with their lives in Hong Kong but they recall the culture shock and language problems they encountered when they first arrived. Rai says one of the reasons he did not study hard at secondary school was because he saw Nepalese did not have many job opportunities. Despite their growing numbers, the Nepalese in Hong Kong still face problems seeking work and education.

“I think people still have the concept of taking us, ethnic minorities, as cheap labour or lower class,” says Rai.

Despite managing to move away from the food and beverage industry, Rai says most members of ethnic minorities still work in the field. According to government figures, nearly 50 per cent of Hong Kong’s Nepalese population are unskilled labourers who earn less than $10,000 a month.

Khatiwada Ganga Kuman, a member of the Far East Overseas Nepalese Association of Hong Kong (FEONA), says non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are trying to change the situation. They are encouraging South Asian people to apply for white-collar jobs instead of limiting themselves to stereotypical manual and unskilled work, such as construction or working as a security guard.

Limbu Saran Kumar, who oversees Nepalese affairs for the Southern Democratic Alliance, believes language lies at the root of the problems Nepalese encounter when looking for work and at work. He says most newcomers hardly know any Chinese and do not have good English either. This makes it hard for them to find jobs and adapt to life in Hong Kong.

“Nepalese children who are born in Hong Kong are able to speak well in Cantonese or even Mandarin, but they are unable to read or write in Chinese, as schools only provide Chinese lessons in junior years,” says Kumar.

Both Kuman and Kumar believe that Nepalese students would be able to enter university and get better jobs if they could get improved schooling conducted in English and Chinese. As things stand, there are only a few Nepalese primary schools in Hong Kong and children from these schools face difficulties when they go to secondary school because their written Chinese lags behind local Chinese children.

Although the government has changed its policy to allow ethnic minority children to apply for government schools, the reduction in the number of schools teaching in English and the relatively low Chinese standards of Nepalese children means they are usually left with only the poorest performing schools to choose from.

Also, most of the information about school choice and application processes are only available online and in English or Chinese. As many Nepalese parents do not have a high level of education, the information is inaccessible to them.

Apart from the problems they face in education and language, the Nepalese community is also grappling with a growing drug problem among its young people. Chris Ip Ngo-tung, a member of the Yau Tsim Mong District Council, says Nepalese youngsters have been seen using drugs in predominantly Nepalese neighbourhoods. Needles and syringes were often seen on the staircases in residential areas. “Neighbours are usually shocked to see the syringes. It creates anxiety among the Hong Kong neighbours,” says Ip.

According to the Narcotics Bureau, Nepali heroin users have currently become the largest group of ethnic minority heroin users in Hong Kong.

Deep Thapa, the chairman of the Hong Kong Nepalese Federation, says the main reason for drug use among young Nepalese are family problems, including the lack of parental care as parents are busy working and devote little time to their children. Many parents find it hard to teach their children, as they are not well educated. Other reasons include the discrimination they may encounter at school and in their daily lives.

Reports on expatriate Nepalese websites have also referred to the sudden freedom young Nepalis are exposed to when they move from a traditional and conservative society in Nepal to Hong Kong, coupled with the lack of guidance from older adults, many of whom choose to stay in Nepal.

Benny Yeung Tsz-hei, another Yau Tsim Mong district councillor, says steps should be taken to help integrate the Nepalese community with the wider Hong Kong community. He says Hong Kong people should understand more about Nepalese culture and vice versa. “There are major differences between the culture of Hong Kong people and Nepalese people in terms of language, food, religion and habits,” says Yeung.

He elaborates by describing how Nepalese people like to gather and have dinner in the streets late at night. These activities can be noisy and anger their Chinese neighbours.

Ip says misunderstanding is the result of a lack of knowledge about Nepalese culture. “The nature of the night gatherings are usually harmonious. It is similar to the way Chinese people like gathering together in Chinatown overseas to get a sense of unity.”

Currently, there are over 40 NGOs working to protect the rights of the Nepalese people in Hong Kong. However, the Southern Alliance’s Kumar says they are not effective and some Nepalese people do not even know they exist. “That is why minorities are not yet mixing in society. They are not involved in implementing ideas or getting people together. That is why there is no progress.”

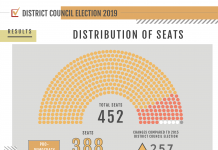

Kumar believes political representation is an effective way to help people solve their problems. Without a Nepalese elected representative, Kumar says, the Nepalese have no voice. That is why he stood for the Yau Tsim Mong District Council election earlier this month.

Kumar came second in the election and missed out on representing his community at the district council level. He says he had never expected to win. “It is hard to compete with the local candidates as the ethnic minorities occupies seven percent of the Hong Kong population,” he says.

He believes the only realistic way for members of the ethnic minorities to have political representation is for the government to allocate one Legislative Council seat for ethnic minority residents to contest among themselves.

Despite losing at the ballot box, Kumar will continue to press for the rights of Hong Kong’s Nepalis. Working to achieve social inclusion and racial equality is a way for him to show the courage and spirit of the Gurkha.