A sense of community returns with the revival of local newspapers

By James Fung

Inside a public housing estate in Shek Kip Mei, several volunteers are distributing a thick pile of district newspapers to passing residents. The single sheet of paper contains articles covering social issues and district matters and is the latest incarnation of Voice of Tai Hang Tung, one of Hong Kong’s earliest community newspapers.

The early 1970s saw a boom in Hong Kong community newspapers with a total of 15 published across the territory. The original Voice of Tai Hang Tung was launched in February 1973 by the resident committees of Tai Hang Tung Estate and Nam Shan Estate, the precursors of the current Sham Shui Po Community Association.

The current version of Voice of Tai Hang Tung is a bi-monthly free newspaper which has been published since the end of 2010 with funding from the community association. Lau Cheuk-kei, one of the publishers, explains that the original paper emerged as a direct result of the Tai Hang Tung Estate’s history. The estate began as a resettlement area, built by the government to house more than 50,000 people made homeless by the Shek Kip Mei squatter area fire two years earlier. It was redeveloped in the 1970s and the newspaper was started as a means of delivering vital information to the large population there. “At that time, when the internet, WhatsApp and Facebook did not exist, the circulation of messages relied on either verbal communication or text written in black-and-white,” says Lau.

The first few issues of the newspaper addressed problems of overcrowding, poor hygiene and lack of security in the Tai Hang Tung community. Before the establishment of the district councils, the resident committees used the Voice of Tai Hang Tung to bring people together to bargain with the Housing Authority and the government on district affairs.

When the plans to redevelop Tai Hang Tung were discussed in the 1970s, the schedule for the works and proposals for resettling residents were announced through the district paper. This shows how important local papers were for disseminating information.

By the end of the 1980s, the Voice of Tai Hang Tung and many other district papers had ceased to operate. Lau attributes this to the improvement of Hong Kong’s overall living conditions – the function of community papers became less important.

Now, with a renewed interest in local culture and community and an increasingly active civil society, community newspapers are making a comeback – albeit in a different way. A monthly district paper, Paper Shau Kei. was launched in Shau Kei Wan in October last year. Pastor Wong King-yip, who founded the freesheet and also funds it, says a neighbourhood is more than a geographical location.

Wong wonders how many Hong Kongers regard their place of residence as their hometown. He spent a year living in Britain around 10 years ago and found that different towns and communities had their own distinctive cultures and character. In contrast, he thinks the classification of districts in Hong Kong means nothing at all. “Hong Kong is like a large shopping mall. District features disappear since chain stores like McDonald’s, Wellcome, ParknShop are everywhere. The boundary of districts is blurred, leaving few peculiar features,” Wong says.

After experiencing the contrast between Britain and Hong Kong, he wanted to reconstruct the sense of community in Shau Kei Wan using a district paper as a communication channel. At first, he thought of producing a magazine with more than 20 pages but this was not practical because it would require money and human resources. He eventually decided to model his paper on a well-known publication already on the market, the single-sheet Black Paper.

Wong says Paper Shau Kei produces three kinds of articles: about the past, present and future. Those about the past cover the old stores and businesses which make up the history of Shau Kei Wan; articles about the present promote current social events, such as the International Dragon Boat Race; while stories involving the future anticipate the cultivation of a sense of neighbourhood.

“Nowadays, people’s social consciousness is weak. You compare this with my father’s generation, those who are now in their 50s, they know everyone in the community,” Wong says. Unlike those from the older generations, Wong feels the Post-80s living in Shau Kei Wan are not familiar with one another and lack a community bond. He believes the greater variety of entertainment choices is one of the reasons for people’s indifference to their neighbourhood. “People used to actually meet up in person, whereas people tend to communicate through electronic means nowadays. Face-to-face interaction is rare,” Wong says.

In much the way they help to cultivate a sense of community, district papers also help found social movements. Whenever a district faces a crisis, its community newspaper can be used as a tool to mobilise residents to protest.

Tai Ping Shan Post is a district paper in Sheung Wan that began publishing in May this year. It originated from a social concern group formed two years ago when the district council proposed building an escalator along Pound Lane in Sheung Wan. This aroused opposition from residents nearby, some of whom formed a concern group to protect their neighbourhood from further development.

Katty Law Ngar-ning and Yeung Tse-kit are core activists of the Pound Lane Concern Group. Along with engaging in the on-going debate over the construction of the escalator, they decided to publish a newsletter to record the historical value of the district and express their enthusiasm for Sheung Wan. “On the one hand, we’re opposed to the destruction, and on the other we need to work harder on the protection of this old district,” Law says.

Both Law and Yeung have a strong sense of belonging to Sheung Wan. Law has lived in the area for over 40 years and currently rents an art studio there. She says the small street-level local businesses in Sheung Wan help form a vibrant local community.

“It is easy for street shops and stalls to make good connections with one another. We help each other to keep an eye on the shop when one has to step out,” Law says. She recalls that on the day of a street forum on the Pound Lane issue, they had not prepared for the outdoor seating arrangements and were caught by a sudden downpour. Fortunately, shop owners nearby volunteered to lend them chairs and offered shelter. For Law, these scenes overturn the stereotype of emotionless and indifferent neighbours in Hong Kong.

Law’s colleague on the paper, Yeung moved to Sheung Wan seven years ago. He regards this district as his one and only home. “I was just like a passer-by in the places I lived before, there was no difference to sleeping in a hotel. I did not really belong to those places,” says Yeung.

The feared destruction of the neighbourhood brought together a group of Sheung Wan fans and prompted them to create the Tai Ping Shan Post. The paper is run by five editors, including Yeung and Law, and they are responsible for conducting interviews with residents in the Tai Ping Shan district and writing up stories. The production of the Tai Ping Shan Post is funded by local people who also help to provide information and content.

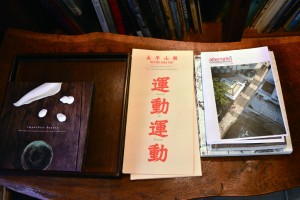

The theme of the first issue was “Exercise for Everyone”, which in Chinese has a double meaning – both physical exercise and social movements. The issue encouraged residents to fully utilise the landscape of the district to develop regular exercise habits. The papers are free and are handed out on the streets in the neighbourhood and left at cafes and restaurants. So far, the publication has received good feedback from readers and has a print run of 1,000 copies.

The age of exclusively print media has gone and the latest local publications reflect that fact and use the internet and even videos to get their point across. V-artivist is an online newsletter founded by Li Wai-yi and his friends in 2007. They all value the relationship between communities and people and Li, in particular, admires the public spaces in the old housing estates that enable neighbours to gather and chat. He thinks it is a pity that new estates lack common areas and so discourage interaction between residents.

Recently, V-artivist published a 180-minute video called The Street, The Way, which compiled 20 human interest stories from districts that have undergone urban renewal.

Meanwhile, the community papers that do publish in print are also using the internet and social networks in order to reach more readers, particularly younger ones. For instance, the Voice of Tai Hang Tung has an online version to supplement its print edition. Publisher Lau Cheuk-kei says the content of today’s district paper is more diverse than the past editions. Rental problems, women’s rights, changes in bus routes and national education have been discussed in issues of the reborn newspaper. It also monitors the performance of local district councillors.

Despite the growing reliance on the internet, Lau wants to maintain the publication of print copies as a physical connection within the community. He prefers not to leave copies of the paper in specific locations. Instead, he insists on giving out the paper copies directly to residents on the street or via home visits to the elderly.

“Tai Hang Tung has managed to preserve the human touch among neighbours. We can pass on the sense of importance attached to community organisations and community newspapers down the generations so that we can preserve this culture,” says Lau.

Edited by Nicole Chan