Making cinemas and films accessible to the deaf and blind

Reporters: Astina Ng and Lindy Wong

“Actor Nick Cheung Ka-fai embraces a little girl and rushes into the building which is a clinic. Once inside [the clinic], Cheung lowers the girl onto a surgery bed,” the narrator, local DJ and voice artist Jacqueline Pang Ching pauses and pants. “A doctor there… takes out… a… knife. What will happen next?”

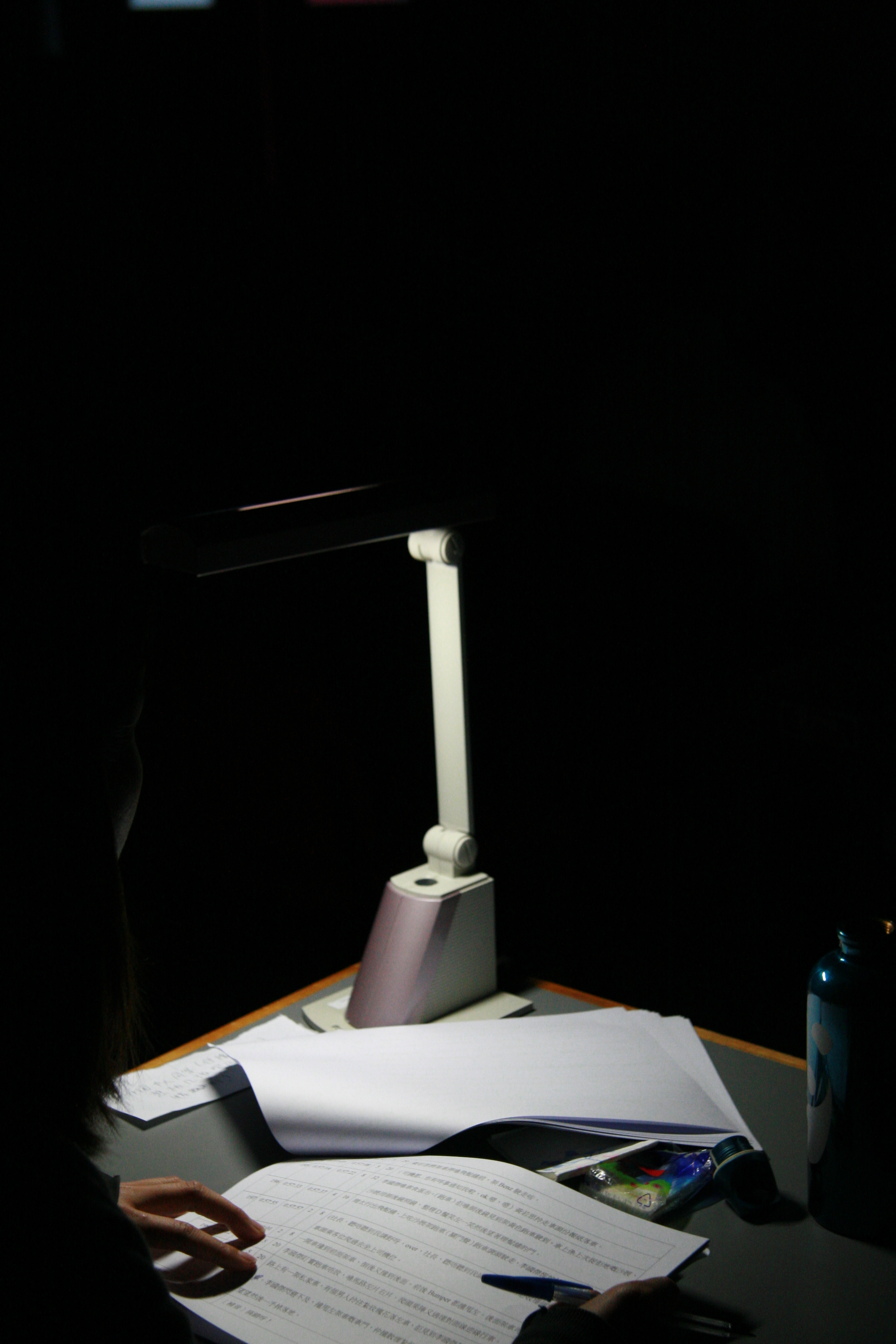

Little sweat beads roll down the forehead of a member of the audience in the hall. He freezes and grasps the arms of his chair tightly. Suspense hangs in the air, a sudden yelp from the audience further heightens the intensity.

Pang is providing a vivid narration of a local thriller, The Beast Stalker, for the audience of blind and visually-impaired people and she certainly knows how to captivate them.

First off, she thinks good narrators must be deeply emotionally engaged. Pang also puts a lot of focus on the mood and the atmosphere. Her passion and charisma infects everyone in the room.

Pang has been volunteering as a narrator for movies for the blind for around three years now and describes this work as a win-win arrangement. The visually impaired are entertained by her performance and she gains satisfaction from using her talents.

She recalls how an audience member was in tears when he thanked her for allowing him to enjoy movies again after many years. She was so touched, she also teared up. “What I did is just simply depict what I see, I had never imagined this little task could bring so much happiness to them.”

While Pang’s experience in radio drama makes her a good movie narrator, she says there are differences between a radio drama and movie narration. For instance, a movie narrator has to deal with the unpredictability of shot changes in a film. Pang jokes that narrating the action sequences in the martial arts biopic Ip Man was like commentating on a horse race.

Not all volunteers are professionals from the entertainment industry. Paul Wong Chun-yui, an accountant, is a scriptwriter for descriptive movies for the blind. To prepare for a two-hour movie screening, Wong had to watch a film seven times and spent his Christmas writing. His biggest challenge was striking a balance between writing descriptions and creating atmosphere.

“Viewing films should not be our privilege, it should be a right for everyone.”

Wong believes the hard work is worthwhile because, “viewing films should not be our privilege, it should be a right for everyone.” Both he and Pang volunteer their services for the Hong Kong Society for the Blind (HKSB).

HKSB pioneered audio description services in Hong Kong and started producing live audio descriptions for movies in 2009. Since then, there have been 77 screenings of films with audio descriptions in the HKSB’s purpose-built assembly hall. The society has recruited 50 volunteers.

According to Emily Chan Lai-yee, the manager of HKSB, the service offers another form of entertainment for the blind. It encourages them to participate in mainstream activities.

Chan says getting operations off the ground was no easy task. At the beginning, she just flew by the seat of her pants. They had no idea of what to describe and how to convey action and details in the films. When Jacqueline Pang Ching started off, she narrated without scripts.

After Create Hong Kong funded the project for a year, HKSB was able to invite foreign experts and hold workshops to promote audio description in movies. Last year, they recruited volunteers for training and developed a more sophisticated system for producing audio descriptions. They now rely on scripts and time their lines precisely to avoid the overlapping of narration and dialogue.

As the number of skilled narrators increases, Chan looks forward to the day when audio description services will be available on public television channels. It would be good news for the 120,000 blind people in Hong Kong.

She also hopes audio description services can be expanded from indoor movie screenings to DVDs. HKSB encourages DVD distributors to include the audio description function for their films. Three DVD titles with audio description distributed by Warner Brothers (Far East) Inc. are Aftershock, Don’t Go Breaking My Heart and Life Without Principle.

Chan urges producers to record audio descriptions of their films throughout the shooting process. That way, the soundtrack of the audio descriptions can be synchronised with the film and the audio descriptions can be available in cinemas when the film is released.

“Just like other countries such as the United States, Britain and Japan, the blind can wear headphones to listen to the audio descriptions without disturbing other people,” she says.

However, Chan adds that few cinemas in Hong Kong have the technical support for audio description. Agnès b. Cinema at the Hong Kong Arts Centre is an exception.

Sadly, says Chan, cinema for the blind is not a mainstream activity in Hong Kong and few people know about audio description. Compare this with Japan, where cinemas provide audio description and facilities and guide dogs accompany the blind to the cinema.

To achieve similar conditions in Hong Kong would require a concerted effort from the government, the film industry and society as a whole.

Wellington Fung Wing, the secretary-general of the Hong Kong Film Development Council (FDC) and assistant head of Create Hong Kong, supports audio description for films and is personally in favour of the production of DVDs with audio description.

However, he believes that if audio description service is conceived of as a welfare service supported by volunteers, it will not be sustainable. On the contrary, if the narrators and scriptwriters are paid, and the distributors can sell more copies due to the extra soundtrack, it could develop into a sustainable business model.

In fact, not much money or skills are needed to produce movie DVDs with audio description. Distributors admit they can cover the costs by selling just 1,000 copies. Yet inertia seems to have overtaken the idea of making more movies available with audio description.

Fung says there is a limit to what the FDC can do and it will not consider proposing any legislation to control or restrict the film industry. It is not compulsory for film producers to add audio description to their productions.

Fung says that what the council is doing is providing financial support to cultivate expertise and promoting the audio description service to DVD distributors.

While narration and sound can bring the visual medium of film alive for visually-impaired audiences, the deaf can also experience cinema just as fully without sound.

Last month saw the second Hong Kong International Deaf Film Festival (HKIDFF) organised by the Hong Kong Association of the Deaf and held at the Agnes b. Cinema in the Hong Kong Arts Centre.

Adam Ng Ying-yung, the association’s executive, says the views of the deaf are often overlooked because they cannot express their thoughts and are considered a minority. People tend to forget that visuals and images are the strengths of the deaf.

Ng says the film festival increases peoples’ awareness of the deaf and audiences can better understand their needs and culture. “Even if the deaf are just a minority, they are still part of the society; we should not neglect their needs,” Ng says.

The HKIDFF showcased films related to the deaf from across the globe, including Malaysia, South Africa, Britain and the United States. The films are not silent movies, they also feature dialogue and soundtracks but they are made by deaf people, feature deaf people and deal with deaf culture.

Among the movies shown at the HKIDFF, there were also productions from Hong Kong, including Reasons for Learning Sign Language – for Deaf People and Deaf Kid Not Stupid. Both films deal with the problems deaf children face when they have lessons using spoken language. “All deaf people are required to learn by lip reading. And sign language is banned at school,” says Kong Wan-ki, director of Reasons for Learning Sign Language – for Deaf People.

Deaf people who view deafness as one kind of human experience, rather than as a disability that needs to be fixed, identify themselves as Deaf with a capital “D”. Sign language is a central foundation of Deaf culture and Deaf identity.

One of the difficulties in organising the HKIDFF was the translation of sign language. As Ng explains: “There is not a universal sign language, so different countries have their own version of sign language.”

When a foreign deaf movie does not have English subtitles, the organiser has to translate the foreign sign language into Hong Kong sign language, before further translating it into written Chinese or English.

Director Kong Wan-ki thinks subtitles should be used to enhance the experience of films for the deaf. Kong says there should be subtitles to indicate music and other background sounds when there are no lines of dialogue. Since the deaf do not learn language in spoken form but in written form, the subtitles should be in the form of written Chinese for the convenience of local deaf audiences.

Kong cites the example of Japan. To avoid confusion, Japanese television programmes use different coloured subtitles to help differentiate the lines of different characters. Each character’s lines are also placed near to him or her to make it easier for the deaf to follow the conversation.

It would only take a bit of effort to make films more enjoyable for the deaf but it also requires a change in mindset. Xavier Tam Siu-yan, vice-chairperson of the HKIDFF Organizing Committee, believes society should stop forcing deaf people to conform to the norms of the hearing. For instance, he says the banning of sign language in schools is a manifestation of oralism and audism.

Audism highlights the importance of hearing and advocates the banning of sign language. The hearing use whatever means to “help” the deaf hear. Oralism is the idea of advocating the use of lip reading and speaking.

Tam believes that both of these ideas are myths which force the deaf to “join” the majority. It is a false hope for them to become “normal”. Supporters of the HKIDFF hope that similar events will help not just the deaf, but also the hearing to step out from the shadows of oralism and audism.