Reporters: Katherine Chan and Melanie Leung

With a cap pulled over his head and a pair of black-rimmed glasses, 22-year-old Jay looks like a typical Hong Kong youngster. His eyes are glazed over with fatigue – not because of endless hours spent playing computer games but from long hours of work, day in, day out.

Jay’s father died when he was young and he came to Hong Kong with his mother and younger sister seven years ago in the hope of a better life. But things did not turn out so well. His mother got cancer two years after their arrival and Jay dropped out of school after form five.

The family survived on Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) and Jay’s part-time job at a laundry. But several months ago, when his sister turned 18, the government cut off their payments. His sister also no longer qualifies for assistance on the vocational course she is taking.

All this means Jay is now the family’s sole breadwinner. “Suddenly, it was all down to me. It is a heavy burden on my shoulders,” he says. He now works 13 hours a day, six days a week at the laundry store for $7,000 a month. “I am a coolie,” he says.

Not only does he have to endure long hours, but also insecurity. Jay’s work schedule is not fixed, he is never certain if he is still needed the next day. His weary, blood-shot eyes begin to well up as he quietly describes the pressure of responsibility. “Every day I wake up and all I know is I must work. If I don’t, then we will have no money. Often I feel too tired to go on, and I cry in my room.”

More than half of Jay’s earnings – $4,000 a month – is spent on rent. In order to help make ends meet, he relies on food handouts from the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals which are funded by the Social Welfare Department. The service provides rice, noodles and vegetables on a temporary basis. “I eat instant noodles for my dinner almost every night,” he says.

While many young people are full of hopes and ambitions at his age, Jay cannot foresee any future. He can only focus on making as much money as possible. Recently, he burnt his right hand on a stove when he was cooking at night but he dared not take a day off work or trouble his sick mother. Instead, he put on a glove and continued working.

To Jay, life offers no alternatives. “It won’t help if I think about the situation negatively. I would only be unhappy at work, and I would make mistakes,” he says. “Why should I even think about it? Making mistakes would cost me my job.” He laughs bitterly at the notion of pursuing further studies. “It’s just a waste of time. The new month is coming up, and I have to pay the rent.”

What keeps Jay going is his family.

Once I realise that I am not working for myself only, but also for my mother and sister, I get over it,” he says. Now he hopes things will improve if they can get a public housing flat. He counts down to the day his sister finishes studying and can share the financial burden.

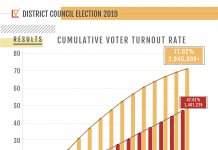

Jay is not alone. According to the research carried out by the Hong Kong Council of Social Service in 2008, 170,000 youngsters were living below the breadline. Young people aged between 15 and 24 have experienced the steepest increase in poverty rates since 2001.

Scott Tam Kin-chung, the training officer of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions Training Centre, believes many cases of youth poverty are the result of cross-generation poverty. Teenagers from poor families quit school to help family finances and end up on low wages, working long hours and in short-term jobs. They have no time for further studies, which affects their long-term opportunities.

How serious is the vicious cycle? A report by the now defunct Commission on Poverty from 2006 showed 247,800 children aged up to 14 years lived in households with incomes below the average CSSA payment. Tam says it is clear these children are not competing on a level playing field with their peers. For a start, they have fewer learning resources. “While

most teenagers stick to their desktops everyday, they have no computer at their home,” he says.

Neither can they participate in other supplementary courses and activities outside school as they cannot afford transport costs. As a result, many drop out and can only get hired on short-term contracts by giant corporations. Tam says companies often employ people during peak seasons and dismiss them afterwards. He cites the case of a youngster who was hired and fired five times by the same company. “It is hard for the poor youngsters to have prospects,” he says.

Lun, 19, is one of the youths facing an uncertain future and he is taking each day as it comes. Currently, he has two part-time jobs. From Tuesdays to Thursdays he works at a community centre; and from Fridays to Sundays he works the night shift at McDonald’s. He makes $6,000 a month from his labour. This allows him to support himself without asking for money from his parents.

But alternating betweenday and night shifts is a nightmare. “I took on the jobs with the mindset that they would be temporary ones while I applied for better ones. But work is so demanding that I no longer have the time or motivation to make applications,” he says.

There is a traditional saying that “knowledge can change fate”. But for Lun, the immediate priority is to support his family as his father is due to retire soon. He left school after completing his A-levels earlier this year and has been working since then. He plans to enrol in vocational courses so he can pursue a better career, such as in the insurance or accounting sector. Lun has decided not to further his education by taking associate degree courses because he does not want to borrow money to pay for his studies. “I’d have to spend the first four tofive years of work repaying my debts,so I wouldn’t be able to save up. And it’s not like I’m going to get a good job anyway,” he says.

While Lun seems resigned to fate, some are unwilling to let poverty get in the way of their ambitions. Joan Ng Wan-mei, 18, grew up in a poor single-parent household but went on to get 3 A’s in the Hong Kong Certificate of Education Examination. “Being poor is not an excuse. All it takes is determination,” Ng says.

She developed her drive early, as a primary school pupil, when her mother was a salesperson earning just $3,000 to $4,000 a month. Although she was unable to afford books and tutorials, she used public libraries and online learning resources. “I do stand at a disadvantaged starting point. But it is only a starting point. That is why I have to work harder than everyone else, or else I would really lose,” she says. As a result of her positive attitude, she was chosen as one of the 2010 Top Ten Model Youth by the We Love Hong Kong organisation.

While poverty has never been a constraint on Ng’s study, it still influences her lifelong decisions. She once aspired to be an architect but she has abandoned the dream as she would have to train for eight years before becoming fully qualified. That is eight years she cannot

afford. Also, the course requires students to make models which would be too costly for her.

Although she is disappointed, Ng is willing to accept reality. “If it can’t be, it can’t be. Many rich people were once poor. Like Li Ka-shing, he became rich out of his own efforts. I don’t believe in unfairness,” she says.

Joan Ng’s determination and academic achievements may make her an exception. Others, such as Jay and Lun, are driven into work, despite the hardship, because of their sense of responsibility towards their families. But there are some young people who neither study nor work.

The Hong Kong Council of Social Services estimates there are 49,000 “non-engaged” young people, who can be divided into five broad categories. Ken Chan Kam-ming, the chief officer of HKCSS lists the five as those with mental problems, the “hidden” or socially withdrawn, the low-motivated, those with specific learning difficulties and Southeast Asian ethnic minorities.

Chan believes one of the most important factors in tackling youth poverty is to motivate them to work. Those currently receiving CSSA payments face a deduction of $200 for every $500 earned. “When wages are so low, it does not make a big difference in their income whether they work or live on aid,” Chan says, “so many choose to rely on the CSSA instead of facing long work hours.”

Chan believes the government should not only change policies that dissuade young people from working but also adopt policies directly targeting youth poverty. As the Confederation of Trade Unions’ Scott Tam says, young people are not poor because they lack a work ethic.

“People say teenagers are unemployed because they are lazy, but those I’ve come in contact with are very proactive in finding jobs. But either they cannot find jobs or the ones they do

find are unstable.”

[…] or on their own. More than any other age group, young people between 15-24 years of age have experienced the sharpest increase in poverty since 2001. That trend isn’t surprising since as of 2011, […]