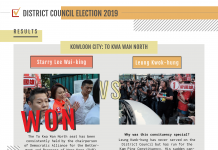

Junior politicians introduce bold ideas to pro-establishment camp

By Yoyo Chan & Hilda Lee

As ever more creative street protests and social campaigns bolster post-handover Hong Kong’s image as the “City of Protest”, the impression many people have is that activists are getting younger and more radical. They are also seen as overwhelmingly pro-democracy.

Dominic Lee Tsz-king is a boyish 29-year-old who became interested in politics while taking a summer course at Britain’s Oxford University as a sixth former and cut his political teeth interning first for US Democratic candidate John Kerry in the 2004 presidential campaign and Democratic Congressman Al Green the following year. Given this history, one would expect Lee to join the pan-democratic camp on his return to Hong Kong after completing his Economics degree.

Not so. Lee joined the Liberal Party and is now chairman of the party’s youth committee. He explains his flirtation with the American Democrats was motivated by youthful disdain for former US President George W. Bush. “To a youngster, George Bush represents something really bad, you don’t want to be associated with anything that is represented by him,” says Lee.

When Lee came back to Hong Kong, he interned at the office of former Liberal Party leader and legislator James Tien Pei-chun and realised his politics were far more aligned with the party of business.

“The Liberal Party is a right-wing political party based upon neoliberalism. Yet, many people hold misconceptions about us. They are confused about whether we are pro-business, pro-establishment or the centre,” says Lee.

Hong Kong has long been a city where free-market and entrepreneurial values are deeply entrenched and they are precisely the values held by the Liberal Party. But small government advocates like Lee feel the city has been drifting in a more welfare-orientated, interventionist direction.

He felt something had to be done to get the Liberal Party’s right-wing image across.

Earlier this year, Lee came up with an unusual move. He noted that Longhair Leung Kwok-hung’s Che Guevara T-shirts had become synonymous with the radical democrat legislator. Lee proposed the Liberal Party should also use a famous figure to illustrate their political ideology.

Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was one of the obvious candidates as an icon of neoliberalism. But there were fears her image might lead to accusations of pro-British sentiment and colonial nostalgia. So, the party plumped for former American President Ronald Reagan instead. A baby blue T-shirt bearing Reagan’s likeness and his quote “The best social program is a job!” has become the new symbol of a party previously associated with business suits.

Apart from that, over the past year, Lee has taken a high profile in expressing his views on social issues. He takes a conservative stance on welfare and gay rights and has raised previously little discussed issues such as government financial aid to asylum seekers in Hong Kong.

Lee believes his proactive approach is necessary after the party’s drubbing in the 2012 Legislative Council Election, in which it won just five seats, the lowest number in its history.

“Speaking of our image, we admit that we have been unclear. If we are going to fight for geographical constituencies again with such an unclear image, only seasoned and well-known politicians such as James Tien could win. There is no hope for newcomers.”

Chu Ho-ting, a political commentator and one of the founders of the Hong Kong Association of Young Commentators (HKYAC), says the pro-establishment camp is keen to recruit young members and is willing to embrace more outspoken young politicians like Lee in order to attract younger voters. He attributes this to the rise of more radical forces in Hong Kong, such as the pan-democrat League of Social Democrats, and the system of proportional representation used in the Legislative Council Election. “Under proportional representation, the League of Social Democrats only needs a few tens of thousands of votes to win one seat. And so they do have their market,” says Chu.

It is not just established parties like the Liberal Party who need new blood. Chu points out that a newly established political party also needs young politicians to gather new sources of voters.

30-year-old Kam Man-fung is the chairman of New People’s Party Youth Committee and an enthusiast in analysing government policies. Chu says newcomers in well-established parties are allowed a limited degree of independence whereas his party is open to young politicians and welcomes their ideas.

Kam says that as some pan-democratic groups and supporters become more radical, the pro-establishment camp needs to be more determined to contend with the voices of opposition. However, he concedes it is in a disadvantageous position when it comes to facing the media.

“Things related to the pro-establishment camp are sometimes really not as juicy,” he says. “It is all about sound bites when you face the media.”

Kam, along with Dominic Lee and Chu Ho-ting, is among the founders of the Hong Kong Association of Young Commentators (HKAYC). The group was set up in December 2012 with the aim of providing a platform for the exchange of ideas and rational debate in an increasingly divided, fractious city. Although it is meant to be politically diverse, apart from Chu, most of the core members are from pro-establishment political parties and bodies, including the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB) and the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (HKFTU).

In July, it organised an open forum on universal suffrage and invited speakers from across the political spectrum. At the pan-democratic end there was Scholarism, People Power and organisers of the Occupy Central movement, and at the other end the radical pro-establishment groups Caring Hong Kong Power and Voice of Loving Hong Kong.

As had been predicted in some quarters, the forum descended into chaos. Arguments broke out between radical pro-establishment supporters and members of People Power, and the speaker from Caring Hong Kong Power leapt onto a table. Although the event had to be suspended, the forum dominated the headlines. Regardless of what had happened, all parties won a considerable amount of media attention.

Ma Ngok, an associate professor of the Department of Government and Public Administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong says the pro-establishment camp and pan-democracy camp have long been fighting for media space. He explains emergent antagonistic groups from the pro-establishment camp, like Caring Hong Kong Power, act by neutralising opposition voices. “They were nobody. But as soon as they stood up, they have occupied the media space, sending out voices that are disproportionate to their prominence,” says Ma.

In a city that enjoys freedom of speech, it should be easy for different voices to find expression. But the New People’s Party’s Kam believes the pan-democratic camp gets more coverage because the mainstream media often find their news “juicier” to report. He says this has created an illusion that many people, especially young people, support pan-democrat causes.

Despite the perception that younger people are getting more radical in a pro-democratic sense, Lee Ka-kiu, a lecturer of the Department of Government and Public Administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, notes there are youngsters inclined to the pro-establishment side. “In university, students majoring in Social Science are more likely to support the pan-democracy camp. But if you ask those majoring in Business Administration, a lot of them are quite conservative or prefer the pro-establishment,” says Lee. He adds many young people working in the business sector are also quite conservative.

As for why more young professionals may be willing to join the pro-establishment camp, Lee points to practical considerations.

“As the pro-establishment camp holds more resources, you could become a district councillor and line up for the Legislative Council election. If you don’t get elected, you could still be appointed to the National People’s Congress or Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. Or if you perform well, you could even be a political assistant or undersecretary. It seems an easier path.”

While the pro-establishment camp may at times appear to blindly support the government, Lee says they have an important role to play and sometimes take similar lines to pan-democratic groups on certain socio-economic issues.

“When you compare the Democratic Party with the DAB, 80 to 90 per cent of their agendas are the same,” says Lee.

The Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (HKFTU) is a traditional pro-Beijing labour group. Despite the group’s pro-establishment tag, 35-year-old Kwok Wai-keung, who represents the HKFTU in the Legislative Council, says he will fight for labour rights. “In a society where the capitalists and workers are somehow confronting each other, you have to be aggressive about labour rights. You can see that we are quite aggressive on issues like standard working hours and paternity leave,” he says.

Kwok says he has to be outspoken in order to attract younger voters, but insists he will not go as far as some in the radical pan-democracy parties. “To be frank, we would not throw things. Rather, we try to create more platforms and space to express our opinions.”

Within the younger ranks of the DAB, Hong Kong’s biggest pro-Beijing political party, there are also signs of a departure from more traditional conservatism.

Chow Ho-ding, the chairman of Young DAB, describes himself as one of the very few people from the DAB to be considered outspoken. For the last three years or so, he has been a regular speaker on the RTHK current affairs programme, City Forum.

Chow says it is rare for people from the pro-establishment camp to take part in the programme. “People from the pro-establishment camp are unwilling to attend City Forum because there is a risk of saying something wrong and of causing problems for other people.”

Along with other members of Young DAB, Chow also writes newspaper columns. As he explains, these are hardly the shock tactics of some of the radical democrats or groups like Caring Hong Kong Power. “To be honest, our supporters would not want us to do radical things,” says Chow, “because our political ideology is rather conservative and we dislike expressing ourselves in eye-catching ways.”

Executive Council member Cheung Chi-kong, who is a pro-government commentator and executive director of the One Country Two Systems Research Institute, says he is not surprised the pro-establishment camp is borrowing some of the pan-democrats’ clothes.

“They are influencing each other. You can’t say you have a monopoly on the way some things are done. You could act in a certain way and I could respond in the same way. It’s like monkey see, monkey do.”

In the jostle to be heard in an increasingly political city, the pro-establishment camp is increasingly competing with opposition voices in more visible and animated ways. As they watch the radical pan-democrats gaining more young supporters, they are becoming more open to the outspoken style of their younger members.

Edited by Matthew Leung