Poll of university students finds more than half want to emigrate from fast-paced, polluted and expensive city

By Rachel Cheung and Cindy Ng

Frederick Au Tsz-ho was 15 and a Form Five student when his family left Hong Kong for Canada. Not wanting to leave his friends and his hometown, he decided to stay behind.

That was five years ago and Au is now studying Civil and Structural Engineering at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Looking back, he regrets his decision. “I feel Hong Kong isn’t right for me,” he says.

It is not the having to look after himself, the cooking, cleaning and other chores that have put Au off life in Hong Kong. What bothers him is the prospect of life after he graduates. “I hadn’t realised there would be so many practical problems after graduation. For example, it is hard to buy a flat in Hong Kong, the high property prices, the price of goods is high.”

The breakneck pace of life, long working hours and the pollution are also things Au says he can do without.

Despite the fact that his mother and sister are thinking of returning to Hong Kong, Au is considering emigrating, preferably to a European country, where he thinks he would not have to contend with so many people and so much pressure.

Au is not the only disillusioned Hong Kong youngster yearning to leave the city. Many are increasingly fed up with the high property prices and fast-paced lifestyle, the frequent social and political conflicts and constant scandals concerning government officials.

A survey conducted by the Hong Kong Institute of Education and other organisations in July this year, found that nearly 40 per cent of the respondents aged between 15 and 34 believed Hong Kong would become more corrupt in the next five years.

With society seemingly more divided and tensions between Hong Kongers and mainlanders increasing daily, emigration has become a hot topic in the city. In order to understand how local university students view emigration, Varsity surveyed 207 students at five local universities (the University of Hong Kong, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and Hong Kong Baptist University).

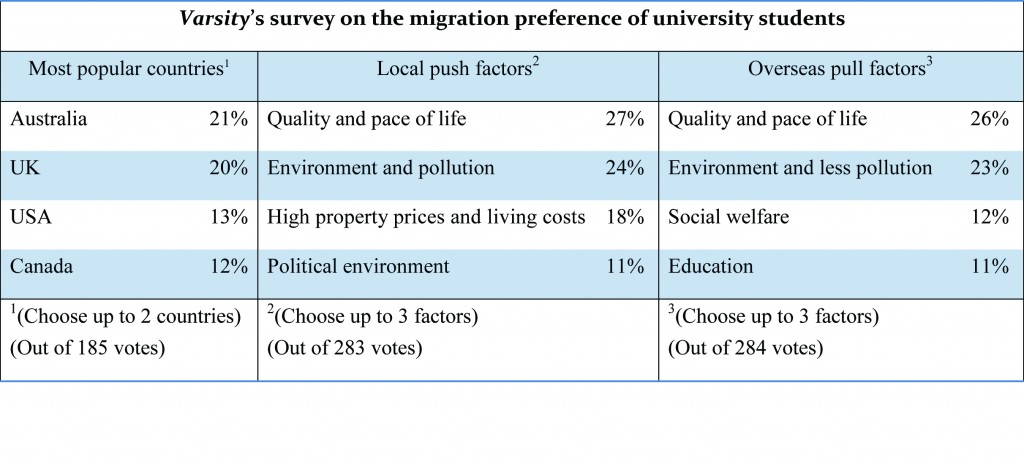

The results show more than 55 per cent of the respondents would consider leaving Hong Kong. The respondents were asked to choose up to three countries they would most like to emigrate to. Australia was the most popular destination, with 21 per cent of the votes, followed closely by the United Kingdom at 20 per cent, 13 per cent opted for the United States and 12 per cent for Canada in their top three choices.

Of the students who wanted to emigrate, the deciding factors were the quality and pace of life, the environment and pollution and the cost of property and living expenses in that order. The political environment was the fourth biggest factor. What attracted students most to their preferred countries were the pace and quality of life, the environment and social welfare.

John Hu, the director of John Hu Migration Consulting, says he is not surprised by the survey results as his business is doing well this year. “[There has been] a hundred per cent increase in the number of clients, compared to 2012.”

He thinks Australia is popular among the students because it sets a relatively low threshold for skilled migrants; for example, a job offer in Australia is not a prerequisite for migration.

However, the country has been reducing the number of occupations it will recognise as eligible for emigration under its scheme for skilled migrants. In July, another five occupations, from the pharmacy and aircraft maintenance fields, were removed from the Skilled Occupation List. Other countries, like Canada, have also tightened their immigration policies. According to the Security Bureau, Canada, Australia and the US are the most sought-after countries for Hong Kong people.

Given the higher thresholds for emigration overseas, Hu suggests university students should acquire at least three years of relevant working experience, rather than pursue a postgraduate degree. “For Australia, a master’s and bachelor’s degree will get you the same points [in the Immigration Points Test],” he laughs.

Hu adds those seeking to emigrate may be facing stiffer competition. Government figures show an eight per cent increase in the number of people who emigrated in the first half of this year, compared with the same period last year.

Mary Chan, an immigration consultant at Rothe International Canada, believes the figures are an underestimation. She says they do not take into account the people who already have foreign passports, came back to live in Hong Kong and now want to leave again. More than 416,000 people left Hong Kong between 1990 (the year after the June 4th crackdown in Beijing) and 1997, the year of the handover. Many of them went to Canada and came back to Hong Kong after acquiring citizenship.

Chan says that in recent years, she has received more enquiries from post-handover emigration returnees who plan to go back to Canada. Education, political uncertainties and high property prices are common concerns. “The children’s education is foremost, it is always because of the next generation,” says Chan.

This explains why 20-year-old Joshua Ng Yuet-shing returned to Canada with his family last August. “In other countries, education doesn’t serve the sole purpose of finding a job,” Ng told Varsity from Toronto. “They [the professors] really want to teach and they really want you to learn something.”

In Hong Kong, Ng’s family had faced financial pressure from high property prices and increasing rent. The family of four moved from a 600 sq ft apartment to a 300 sq ft one. “Middle-class people like us aren’t given any breaks in the [government’s] budget announcements,” he adds.

Runaway property prices are a headache for both the government and those who do not and cannot own a flat. Some scholars argue property ownership is the bedrock supporting the younger generation’s material and emotional attachment to a city.

“If young people can’t even afford a flat, how can they build the sense of belonging to this city?” asks Chung Kim-wah, an assistant professor of Applied Social Science at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Earlier this year, Chung held a focus group to conduct research for the government’s Long Term Housing Strategy Steering Committee. During a discussion among young professionals, one said he would rather emigrate than save to buy a tiny, expensive flat in Hong Kong. Others immediately jumped in to agree. “The anger of young people is obvious. Even if they work hard to save money, a price surge in the property market can wipe out their years of effort,” says Chung.

Chung says he has observed that the people who have emigrated in recent years have been younger than those who left in the great outflow of local people in the 1990s. Besides property prices, he says the changing political environment and expectations of young people have also been factors.

“Young people now look for self-development, more freedom and private space,” he says. “They now want to engage in politics more actively but the political environment is getting more repressed.”

However, Victor Zheng, the co-director of the Centre for Social and Political Development Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, plays down any talk of a new wave of emigration. “Emigration is a very important decision. [Mass migration] is not going to happen unless there are huge incidents, like a massive riot in China, political persecutions or an outbreak of disease.”

Zheng views the current migration levels as normal and even desirable. “Normal flows of people can facilitate social mobility to a certain extent. People leaving from the high positions will create vacancies for the others to fill,” he explains. Despite widespread discontent with the government and deepening social problems, Zheng believes Hong Kong people’s sense of belonging remains strong.

This is not how some Hong Kong émigrés see it. Aaron Ng Ka-hing, 30, moved to Australia in 2002 to study Business. He found a job in Australia soon after graduation, so he stayed.

He now lives in Melbourne and runs an online retail platform. From time to time, he considers seeking investment opportunities in Hong Kong. However, the Hong Kong political environment often discourages him from doing so. “There are many uncertainties in the policies. I cannot see which direction the new government is leading Hong Kong,” Ng says.

Among his list of concerns, Ng cites intensifying political conflicts, the hegemony of the property developers and an imbalanced economic structure that is skewed towards the financial sector. “There are too many grievances. The political environment is unstable and there is a lot of negative news. [A place like that] can’t hold on to dynamic people.”

But as many young people dream of leaving, or are even making concrete plans to do so, some are opting to come back.

Doris Cheung Pui-ying, 30, returned to Hong Kong after living in Canada for 15 years. She has swapped a three-storey townhouse in Canada for an 18 sq ft bedroom in the flat where she now lives with her family. She made the move for her career. “I have been in the same position for six years [as a manager in Canada] but I always wanted to earn more,” she says. Cheung thinks there are more business opportunities in Hong Kong.

Coming back has been harder than she expected. The marked reduction in living space is not the biggest problem, rather it has been her difficulty in adapting to local people’s values. “Hong Kong people are more snobby,” she says. Recalling a gathering with friends and their colleagues, Cheung says: “One of the first things they asked me was where I lived, I answered Tsing Yi. After that, they didn’t bother to pay attention to me.”

Cheung has also noticed that people are generally more disgruntled. “When I read the papers and listen to the news, it seems the whole society has become more negative than it used to be. It used to be happier.”

Despite all these obstacles, Cheung is willing to stay in Hong Kong to strive for a better life after she retires – to Canada. Deep in her heart, Canada is still her real home. “I should grab the opportunities when I am young, then I will enjoy my life in Canada.”

Edited by Caleb Ho