Parallel traders merely the latest new phenomenon in this former rural backwater

By Ian Cheng and Natalie Cheng

Sheung Shui station is the last stop on the East Rail Line before passengers in Hong Kong reach mainland China. Positioned close to four major access points to the Mainland, today’s Sheung Shui has taken on the feel of a modern day Silk Road trading post with Chinese characteristics.

Cross-boundary parallel traders crowd the platforms of the train station with cartloads of parallel goods, ranging from milk powder and cosmetics to iPads and mobile phones, turning this former sleepy market town into a hub for those who buy goods in tax-free Hong Kong to resell in the Mainland.

The rapid development of Sheung Shui in recent years has caused some parts of it to become unrecognizable. More and more shopping centres have sprung up and the types of shops found in the town have changed as well.

Pharmacies, jewellery shops, and health care retailers and chain stores, mainly catering to mainland consumers, have multiplied, pushing out independent local businesses.

“Things cost more and there are fewer choices,” says Leung Wai-sze, a freelance writer in her early thirties who has lived in Sheung Shui since the age of two.

In September, protesters responding to a call on the internet to “reclaim” Sheung Shui, gathered outside Sheung Shui station. They complained that parallel traders had pushed up the prices of local goods and caused disturbances to daily life for residents in the town.

Leung wrote an article later that month, describing the changes and impact of development in Sheung Shui since the 1980s.

“I tried to interpret my feelings… that is to say if I want to ‘reclaim’ anything, then it is the life that we had always enjoyed before [in Sheung Shui],” she says.

The article struck a chord and was widely shared on social networking sites. Among those who share her sentiments is Andrew Choi Tsz-hong, a 22-year-old journalist who was born and raised in Sheung Shui. Choi feels uncomfortable about the changes to his home town to the point where he feels it is gradually being stolen by mainlanders.

“Shopping in Tsim Sha Tsui is acceptable, as Hong Kong is a tourist place, a shopping paradise. However, Sheung Shui is not for tourists. Buying daily necessities that are supposed to be for local residents is not a normal phenomenon,” Choi says.

For youngsters of his generation, Sheung Shui’s shopping malls were a place for leisure and socialising. Choi says this has completely changed. Restaurants like KFC and Pizza Hut were regular hang-out joints for local youths, but these are now gone, replaced by stores selling gold and luxury handbags.

Choi says that when he sees parallel traders queue up in front of the train station, and hears them speaking in Putonghua, or when they run into him with their trolleys, he feels alienated from the place he has lived his entire life.

The Sheung Shui of today may seem a world away from the Sheung Shui of Choi and Leung’s childhoods, but even that is another world away from the Sheung Shui of not long before they were born.

Before urbanisation, the area that is now Sheung Shui was made up of villages, including centuries-old walled villages, a couple of market towns and acres of farmland.

It would have been a common sight to see farmers herding cows across the narrow-gauge railroad and to hear Hakka songs being sung by old women.

“I lived in a village at that time,” says school teacher Simon Wong Yun-keung who is also a serving District Councillor in the area. “[We] could buy fresh vegetables, or plant them ourselves. [Sometimes] people peddled them at your door.”

Wong moved to Sheung Shui to teach more than 30 years ago and misses the days when he would ride his bicycle home after work and make a cup of coffee to sip on his second floor balcony while he sat down to mark students’ workbooks.

The village was a small and close-knit community where everyone knew each other and outsiders were easily spotted. “When I first moved in, I needed to introduce myself to all the villagers. Dogs would bark at you if they did not know you,” Wong recalls.

As the only “immigrant” from the city, Wong got a taste of community he had never experienced before. During the Dragon Boat Festival, he was invited to share the joy of wrapping hundreds of rice dumplings with other residents, and he was regularly invited to tea gatherings.

Whenever something happened in Sheung Shui, everybody was in it together. When a resident had to build a wall in the garden, he or she would invite five or six households to help out; and whenever an expectant mother needed medical help, the men would escort her to the village entrance and wait for an ambulance.

Before North District Hospital was constructed, the nearest hospital was in Sha Tin. Complications during pregnancy could be dangerous, especially in cases of premature labour. The road leading to the village was not wide enough for an ambulance to pass through.

Before the railway was electrified in 1983, Sheung Shui was seen as a backwater. Minibuses and diesel trains were the only public transport available.

“The train ride lasted for at least one hour from Mong Kok… and each train came every other hour, so when you missed one, you had to sit at the station for a long time. It was very inconvenient,” says by Wong Chi-wah, the former district councillor for Shek Wu Hui constituency and a retiree who has lived in Sheung Shui for 40 years.

When Wong Chi-wah first moved to the area, the border between Sheung Shui and Shenzhen was simply separated by wire fences and gates. Residents from both sides of the border travelled easily back and forth. Residents recall that farmland near the border was shared between Sheung Shui and Shenzhen farmers and the two groups of people got along very well.

However, after years of development, most of this farmland has been replaced with commercial and residential buildings. While he rues the loss, Wong Chi-wah says that “we can’t always have rural villages… sacrifices have to be made for society to develop.”

Wong thinks the electrification of the railways played a pivotal role in transforming Sheung Shui from a rural backwater into an urban new town. The development of Lo Wu station and the opening of the line from Sheung Shui to Lok Ma Chau in 2007 further encouraged greater interaction and integration with the mainland.

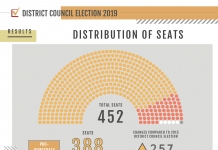

The population, which shot up from 10,900 in 1986 to around 220,000 now, has largely contributed to the development of the area.

The first big wave of development and urbanization in Sheung Shui actually took place in the early 1980s when the first public housing estate, Choi Yuen Estate, was built. Later, Home Ownership Scheme flats like Yuk Po Court, Choi Po Court and other estates were also built, further expanding the population.

But unlike the current reaction to the transient mainland traders and visitors in Sheung Shui, this wave of urban newcomers does not appear to have encountered much opposition.

The difference, for old-timers like Wong Chi-wah, is that today’s scenario feels like an intrusion. Like the protesters calling on residents to “Reclaim Sheung Shui”, Wong Chi-wah thinks there are not enough hospital beds for pregnant local women, since mainland mothers started to travel to the town to give birth. School places are also limited since mainlanders want their children to be educated in Sheung Shui and there is even competition for daily necessities such as milk powder.

“If a well has unlimited water, then we could share it with outsiders, with other residents, with tourists. No problem. But problems will occur if we only have a barrel of water, we do not even have enough water for ourselves and we have to share it with other people,” says Wong.

But for the current district councillor, Simon Wong, the idea of an “intrusion” in Sheung Shui does not make sense, whether it was 30 years ago or today. “You have your own living space and activity space,” he says. “The influx of people is an inevitable phenomenon of social development.”

Despite the drastic changes that have taken place in Sheung Shui in recent years, it has retained some of its distinct local character and businesses. Most of these are centred in and around Shek Wu Hui, which has been the site of a market serving the villages in the Sheung Shui area since before the development of the new town.

Shek Wu Hui hosts a temporary market known as the Sheung Shui Open-air Bazaar, which is a market for unlicensed hawkers in Hong Kong. The space was donated by former Legislative Councillor and notable New Territories figure Cheung Yan-lung for hawker activities around 20 years ago.

The market, which is open between 6 a.m. and 10 a.m., is popular with local hawkers, as vendors do not need to have licences or pay rent to set up. Every morning, they queue up in front of the gate and wait for staff from the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department to open up.

One of the hawkers, who gives her name as Ms Lee, started to sell her home-grown vegetables at the market a few years ago. Every morning, she brings her produce over by bicycle.

Most of her customers are local residents, but some travel from other districts like Tsuen Wan or Tsing Yi, attracted by the distinctive fresh vegetables. Over time, some of the customers have become her friends.

The words “unlicenced hawkers’ market” might conjure up images of a crowded, dirty environment but the market is in fact clean and orderly. Singing can be heard at times and most of the hawkers are friends with each other. “Many of us live in Sheung Shui. We see each other every day so we help each other when needed,” Ms Lee says.

The spotlight on the parallel traders around Sheung Shui station may highlight one facet of a town that residents feel has changed beyond recognition. But in places like Shek Wu Hui, some of the old bonds remain.

Nothing, however, can really compare to the dramatic changes of the 1980s when the construction of the New Town and the arrival of the electrified railway redrew the landscape.

Even old-timers like Wong Chi-wah, himself once a newcomer, think it is unrealistic to reminisce about the old days of rural life. Instead, he hopes the government will address the tensions arising from increased cross-boundary economic activities and the social impact they bring.

Still, for some of the post-80s generation who grew up in Sheung Shui new town, the needs of the local community and respect for their way of life should not be sacrificed for greater integration with the mainland. “I hope the changes can be organic, which means letting [Sheung Shui] change itself over time,” says writer Leung Wai-sze, whose paean to her hometown struck such a chord with so many.