Purists fear simplified Chinese characters will replace traditional characters in Hong Kong

Reporters: Rene Lam, Natalie Cheng

Graduate student Wang Tiexin uses traditional Chinese characters in his reply to Varsity’s interview request through text message. He also uses traditional script in many of his posts on social networking sites, yet in person, his soft Mandarin accent hints he may be from Taiwan.

In fact, Wang, who is studying at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), is from Chengdu in Sichuan province and learned to write traditional Chinese by reading subtitles and lyrics from popular songs sung by Hong Kong and Taiwanese artists.

Although simplified Chinese is the official script in Wang’s homeland, he prefers traditional Chinese and believes that the traditional form “makes more sense”.

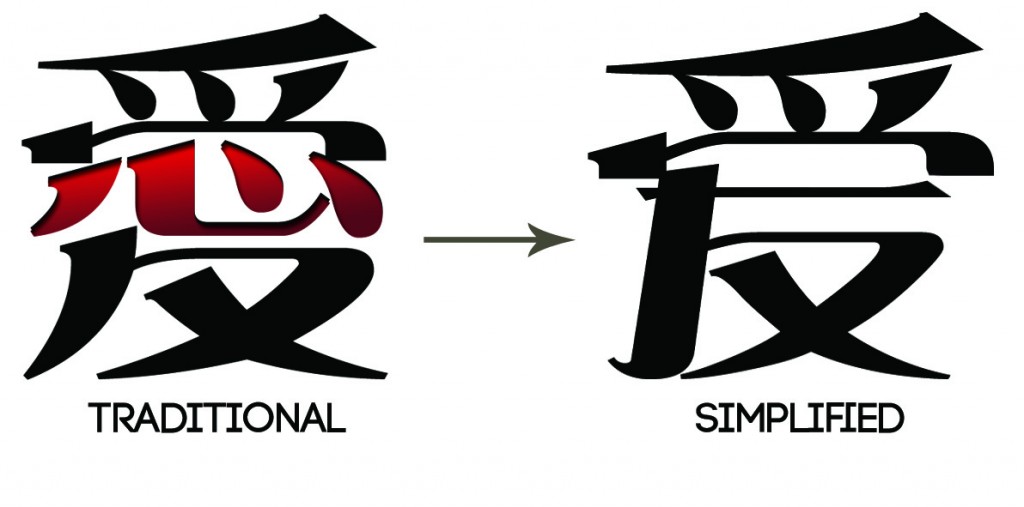

“The simplified form of ‘love’, is without ‘heart’,” says Wang enthusiastically while writing the Chinese character “ai” in the air with his finger. “In traditional Chinese, there is a ‘heart’ in the middle of the character and it means something.”

Wang believes traditional Chinese characters are not only structurally beautiful, but educational as well because of their intrinsic meaning. And since he regards learning traditional Chinese an “acculturation”, an integral part of Chinese culture, he is appalled that some of his Chinese friends cannot read traditional characters at all.

He was even more dismayed when he heard that Hong Kong had started using simplified Chinese characters for official notices. Wang believes different regions of China should have their own culture and retain features unique to their region. He fears the use of simplified characters is a sign that Hong Kong is becoming more like the mainland.

Reports in December last year about an official sign written in simplified Chinese in the New Territories sparked anger and fear in the Hong Kong community and beyond. Online groups and forums supporting the traditional Chinese writing system sprang up, igniting debate over the official language of Hong Kong.

Although the Hong Kong Police Force and the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department explained that they had used simplified Chinese merely for law enforcement purposes, many remain unconvinced. They take the move as a sign of the gradual abolition of traditional characters in Hong Kong.

“The Basic Law specified that [Hong Kong’s way of life] would remain unchanged for 50 years. But this clearly is not the case,” says Trevor Ma Chong-sum, the initiator of the Facebook group, “Say no to simplified Chinese; only traditional Chinese in Hong Kong”.

“I am worried that the public will gradually forget that simplified Chinese actually stems from traditional Chinese and that traditional Chinese is the actual root of Chinese,” he says.

Ma is disappointed with the increasing use of simplified Chinese in Hong Kong – pointing to examples from restaurant menus to billboard advertisements. He believes these changes are merely ways of “accommodating mainland consumers” and he thinks they are “intolerable”.

Ma, a recent University of Hong Kong graduate who works at a bank, takes great pride in writing in traditional characters. He believes it identifies him as a Hong Kong citizen.

His Facebook page was created in late December last year with the intention of defending the orthodox script in Hong Kong. It has drawn more than 1,300 members and the number continues to grow every day.

To raise awareness of the seriousness of the problem, the group encourages people to take photographs of public signs and notices written in simplified Chinese and to post these images online. Members also plan to start a campaign that encourages people to paste a traditional Chinese version of a sign beside every one which is in simplified Chinese.

Ma insists that he is not acting out of a belief that one set of characters is superior to the other but because he believes traditional Chinese characters “create a sense of identity”.

For the cultural critic Chan Wan, the social phenomenon of safeguarding traditional Chinese in Hong Kong shows the “awakening” of people who realise there is a need to protect their own values.

“We are all well aware of how the mainlanders are ‘invading’ and ‘occupying’ Hong Kong, but even so, the government doesn’t seem to be doing anything to help solve this problem.”

Chan, who is an assistant professor at Lingnan University’s Department of Chinese, says simplified Chinese has “zero value” in Hong Kong. Chan adds the only exceptions are in the boundary areas between Hong Kong and China where there are large numbers of mainland Chinese commuters travelling in and out of Hong Kong.

What is more, he argues that mainlanders can often decipher the meanings of traditional signs since simplifed Chinese characters are derived from traditional Chinese ones. Besides, just under a quarter of Chinese characters are actually simplified; most still bear their traditional form.

Chan blames the government for failing to act to sustain Hong Kong’s traditions and values. He predicts that if people continue to turn a blind eye to changes in the writing system, simplified Chinese will soon replace traditional Chinese in Hong Kong.

The furore over the simplified Chinese road signs illustrates Hong Kongers’ anxieties over the territory’s autonomy and cultural identity. But aside from the cultural and political significance of traditional characters, its defenders also emphasise there are other values that make them worth preserving.

Chan Chi-hung, a language instructor in the Chinese Department at the University of Hong Kong, is sceptical about the hullaballoo surrounding the debate about traditional and simplified characters. He says the discussion has become too emotional.

“When you ask Hong Kong people, which characters do you prefer, traditional or simplified? Many students would say they prefer the former. Yet from my daily observations as an examination marker, I realise a lot of students actually write simplified Chinese unconsciously when they need to be fast,” Chan says.

For Chan, the value of traditional characters lie in the characters themselves. He supports the use of traditional characters because of his passion for Chinese culture and literature.

For instance, Chan believes it is better to study the Chinese classics in traditional characters because simplified Chinese fails to distinguish between certain homonyms.

Take the character “hou”, which in simplified Chinese means both “back” and “queen”. In traditional Chinese, these are two different characters. In simplified Chinese, the complicated character is replaced with a single simplified form which creates confusion especially when reading Chinese classics.

In most Chinese classics which are written in the traditional script, monosyllable words (zi) are used instead of polysyllable words (cihui). Hence knowing the exact meaning of each specific traditional Chinese character is crucial to comprehending the meaning of the entire sentence.

Chan believes people should protest against such simplification but that taking such a stand against simplified Chinese would be superficial without a true understanding and passion for Chinese literature.

He hopes debate sparked by the road signs will make people aware of the issues involved and that the government will do more to preserve Hong Kong’s culture of using traditional Chinese.

Scholars of classical Chinese are not the only advocates of traditional characters; they are also preferred by graphic designers.

Edmond Lai specialises in designs based on re-creating Chinese characters. He draws his inspiration mostly from traditional characters, which he finds more structurally appealing and also more expressive.

“Traditional characters are derived from pictures and as such their meanings are easily comprehended,” Lai explains.

Lai views the meaning a character conveys as the most crucial principle for Chinese character graphic design. If a simplified Chinese character were more expressive, he would choose it over a traditional one. However, this is rarely the case.

Lai believes most simplified characters have lost their uniqueness and are not artistically appealing.

But while advocates of traditional Chinese characters see them as being the more authentic and “pure” form of written Chinese, others point out traditional characters are themselves simplified forms of earlier characters.

Cheung Kam-siu, assistant professor of the Department of Chinese Language and Literature at the CUHK, explains that the Chinese language system can be traced back to the Shang Dynasty, with the emergence of oracle bone script (jiaguwen). Since then, Chinese characters have undergone numerous stages of simplification.

The earliest Chinese characters were logographic, based on pictures. However, lines and marks began to replace pictograms after the Warring States Period. Seal script (zhuanshu) in the Qin Dynasty, which requires balanced forms and smooth lines, represents a breakthrough in Chinese character history.

As the pictographic meaning in Chinese characters disappeared, it was replaced by simple lines. According to Cheung, this means the argument that simplified characters lead to the loss of the original meaning of Chinese characters is flawed.

He says traditional Chinese characters, despite their name, have in fact already travelled a long way from the roots of the written language. The unending pursuit of convenience has led to the logical emergence of the simplified Chinese characters we know today. It is a natural and inevitable process in the evolution of Chinese writing.

Cheung believes we should respect both traditional and simplified Chinese characters and learn to appreciate and accept simplified characters as one of the modern standard written systems.

He is not surprised that simplified Chinese has appeared more frequently in Hong Kong after the handover as there are now more mainlanders visiting and living in Hong Kong.

From purely a linguistic point of view, Cheung says words are merely symbols that denote and encode messages. If these characters, or put simply, symbols, are able to function effectively as a tool for communication, then they would have served their purpose.

He cites the example of signs in Hong Kong hotels which use English, traditional Chinese, simplified Chinese and even Japanese in order to communicate with customers.

This diversity in languages is solely for practical purposes and the same principles should apply to public signboards and banners. Cheung says political and socio-cultural factors simply do not come into play.

Cheung is confident that traditional Chinese writing will never fade out as he recognises the huge support it has from Hong Kong people. Nevertheless, he thinks that the public should improve their understanding of the Chinese language and culture before any genuine and fruitful debate can ensue.

“When we put too much political emotion into [the debate], we forget to look into the reality of the language.”

– An earlier version of this story and the print version erroneously states that zhuanshu appears in the Han dynasty. The online version has now been corrected to the Qin dynasty. We apologize for the mistake.