Hong Kong’s politically aware millennials are challenging the traditional idea of family

By Kelly Wong & Achlys Xi

Studying in her final year at university, 22-year-old Queenie Chung Xiao-qing has a promising future ahead of her. It is a future she envisages with a husband and children. “I want to get married at 26, the earlier the better…and give birth before 30, to maybe at least one or two children,” she says, wide-eyed with excitement. “Having only one child could be rather boring. Two kids seem much better – perhaps a boy and a girl.”

But as she continues, and she begins to consider the difficulties she may have to face raising a family in Hong Kong, her excitement dims. Even before the 79-day Occupy Movement began, the city had become increasingly polarised, with deep rifts between generations and within families over Hong Kong’s political future and social and cultural values. This has, to varying degrees, affected young people’s views about family – what the concept means, their ties with their families and their desire to form one of their own.

For Chung, Hong Kong’s political situation is a disincentive for her to start a family. “Currently [in Hong Kong] the idea of ‘One Country’ has predominated over the idea of ‘Two Systems’, which makes me worry [about communism and Hong Kong’s future].”

Chung was an active participant in local politics, being a former convener of Scholarism and a member of the Kwu Tung North Development Concern Group.

She is majoring in Chinese language studies and education, and is also worried about the quality of education for her future child. “I will definitely not [send my child into] mainstream schools. As I also study education, I find [the pressure at mainstream schools] hard to withstand. International schools would be the only choice, but then the cost might be out of reach.”

At home, Chung describes her relationship with her family as so-so. “My parents embrace the traditional idea of ‘valuing the sons more than the daughters’ and always pay more attention to my younger brother,” she complains.

Apart from their views on gender differences, Chung also has different political values to her parents. Although they are broadly supportive of democracy, Chung says her mother would have stopped her camping out on the streets during the Occupy Movement if she could because she thought “other people will do it for you”, whereas Chung says she believes that attaining true democracy requires people to make their own effort.

She says she finds her parents’ values and the way they handle differences disappointing, “I am not asking that everyone has the same values in a family…I can accept differences, but my family cannot.”

She says her own relationship with her parents and a desire to do things differently has influenced her eagerness for early marriage. “My parents couldn’t give me the happiness that I wanted. Therefore when forming my own family, I shall not repeat the same mistakes.”

Chan Kin-man, associate professor of sociology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and one of the co-founders of Occupy Central with Love and Peace, observes that this generation of young people faces more conflict with their families because of different political values. “Unlike the previous generations, this generation of youth [born after the handover in 1997] no longer view Hong Kong as merely a labour market or a consumer market. They value Hong Kong as their home – thus their expectations [for Hong Kong’s future] are also different.”

Chan says the Occupy Movement was a catalyst for worsening family relations. “These [conflicts between different values] have been accumulating. Beijing’s increasingly tight grip on Hong Kong affairs since 2003 has made our society more divided politically. During the Occupy Movement, when the society was at its breaking point, intimate relations between many families, lovers and friends were greatly affected.”

He is currently conducting a study on how social movements influence family relationships. He says family is still important although most young people in this generation do not identify with the political values of their parents. “Family is still very important in Hong Kong as a Chinese society.”

Chan elaborates by describing a phenomenon that he has noticed in his sociology class. “Every year, I would ask them [students] to draw a picture that reflects the ‘happiest moment of your life’. Most of them ended up drawing moments they spent with their family, for instance having dinner together in front of television. Such emotional support is especially important, which explains why they treasure family a lot.”

Unlike Queenie Chung, 19-year-old Heily Wong Hei-lam has a happy home life. She is close to her parents and receives emotional support from them. Her political stance is also not as strong as Chung’s.

University freshman Wong says she does have arguments with her parents, usually over aspects of her personal life. “They often complain about me getting home late,” she says. “But many of these conflicts are quickly resolved…they [parents] are quite open to discussion.” She thinks it is always important for her parents to express their understanding.

Wong adds she usually avoids discussing politics at home to minimise conflicts and that sharing similar values with her family members helps her to build stronger emotional bonds with them. “If I had to prioritise the importance of my family and friends, family definitely comes first,” she says.

Wong says her parents have given her considerable freedom when it comes to how she wants to form her own family – they would accept cohabitation and children before marriage. “A few of my relatives gave birth before getting married. My parents find that normal,” she says. As for her own thoughts on marriage, Wong thinks it is optional as she is eager to date different men before settling down, and she is not concerned about the issue of whether she will have a child or not.

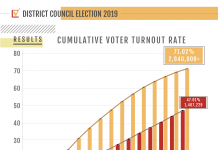

Her views are not unusual. In a survey of 346 people aged between 18 and 27, Varsity looked into the changing concept of family among this generation of Hong Kong youth. Compared with surveys conducted by other organisations in the past, we found marriage and having children have become less popular while various aspects of the traditional idea of family are being challenged.

Results showed that only half of the respondents say they intended to marry in the future, whereas a 2011 poll by the Family Planning Association of Hong Kong found nearly 60 per cent of respondents aged between 18 and 27 said they were intent on marriage.

Varsity’s poll also shows that only 47 per cent of respondents are willing to have children in the future. Among those who do want children, most would prefer to do so before they are 30. Nearly half of the respondents agreed the current political situation in Hong Kong has made them less willing to have children. In the Family Planning Association’s 2011 survey of 1,223 people aged between 18 and 27 nearly 60 per cent of young people said they planned to have children.

While fewer young people seem to be keen on getting married and having children, they attached great importance to friends. Half of the respondents thought family and friends were equally important, while nearly 60 per cent of the respondents accepted non-monogamous open relationships.

The survey suggests young people have a broader concept of how a family can be formed which is less restricted to those related by blood and living under the same roof. This reflects the view of 20-year-old Fiona Chow Tze-ching. “If intimate friends [give me enough emotional support], they can be [my family] too,” says Chow. “Getting along well and having mutual understanding is crucial…family love might occur among some of my closest friends.”

Chow also supports the idea of open relationships – namely having multiple relationships at the same time. She thinks the feeling of intimacy and “living in the moment” overrides the traditional value of commitment within a family. To her, it is the degree of emotional support and intimacy between people that is most important. She believes the more effort you put into a relationship, the more intimacy you feel and the more likely it is that you will regard the other person as a family member.

Elaine Au Liu Suk-ching, associate professor of the Department of Applied Social Sciences at the College of Liberal Arts and Social Science at the City University of Hong Kong has conducted extensive research on youth and their relationship with their families. She says the idea of family has evolved over time and the traditional concept of family currently faces an onslaught of challenges. Increased peer influence and the higher level of education among this generation of young people add to the pressure for a more open and fluid concept of family, says Au.

“Society has been more open for discussion on these issues [on the changing concept of family]…when I was at primary school, if my classmates’ parents got a divorce, it was somehow a taboo to tell. And now it is open [for divorced couples] to tell people about it.”

How people think a family can be formed has also changed radically. “For example, when people talk about the definition and nature of family in the United States these days, those who are unmarried and live by themselves would disagree that they do not have a family. They would argue that they have pets as well as friends, who they feel intimate with. They feel like they have a home. It is therefore no longer appropriate to say that these people do not have a family.”

She also sees many possible family formations – between two men or two women, or even between a man and an object such as a piece of furniture as long as there is an intimate emotional bond there. “Who knows what will be next?” she muses.

So, will the traditional concept of family breakdown in the face of these multiple interpretations of family? Au believes every development in the concept of family – be it pre-marital pregnancy, open relationships or even friends as family – does not change the fundamental basis of family, which is living collectively for survival.

“Our ancestors decided to live collectively, not individually, by forming families. We have lived collectively for survival throughout centuries. That will not be replaced over time.” Every young generation introduces new ideas and behaviour to the notion of family but Au believes that, for now, intimate emotional ties will continue to be the most important factor for this generation of young people in forming their own families in the future.

Edited by Thomas Chan