Hong Kong’s young people respond to political stalemate one year after Occupy

By Emily Man & Jayce Lai

Tears streamed down Jasmine Choi Yan-yan’s face when she was arrested in the forecourt outside government headquarters. At midnight on September 26, 2014, she and other youngsters had heeded the call from student leaders to break into Civic Square, as it is known, and “reclaimed” the space.

“I felt aggrieved for Hong Kong, it’s like we’re being bullied. What we did was justified,” says Choi, a 22-year-old fresh graduate from The Chinese University of Hong Kong, her voice still shaking as she recalls the most unforgettable night in her life.

It turned out to be the opening act in what became the 79-day Occupy Movement to demand fair and open elections by universal suffrage for the 2017 Chief Executive election. During the movement, Choi spent countless nights on the streets and ended up getting pneumonia.

After her arrest, Choi was denied access at the border to mainland China and questioned by officers in a tiny room for hours before being sent back to Hong Kong. Looking back, she feels that all her actions and sacrifices were useless.

“If the former Chief Executives had faced such a large-scale protest [Occupy Movement], they wouldn’t have been able to ignore it. But now they don’t care at all.”

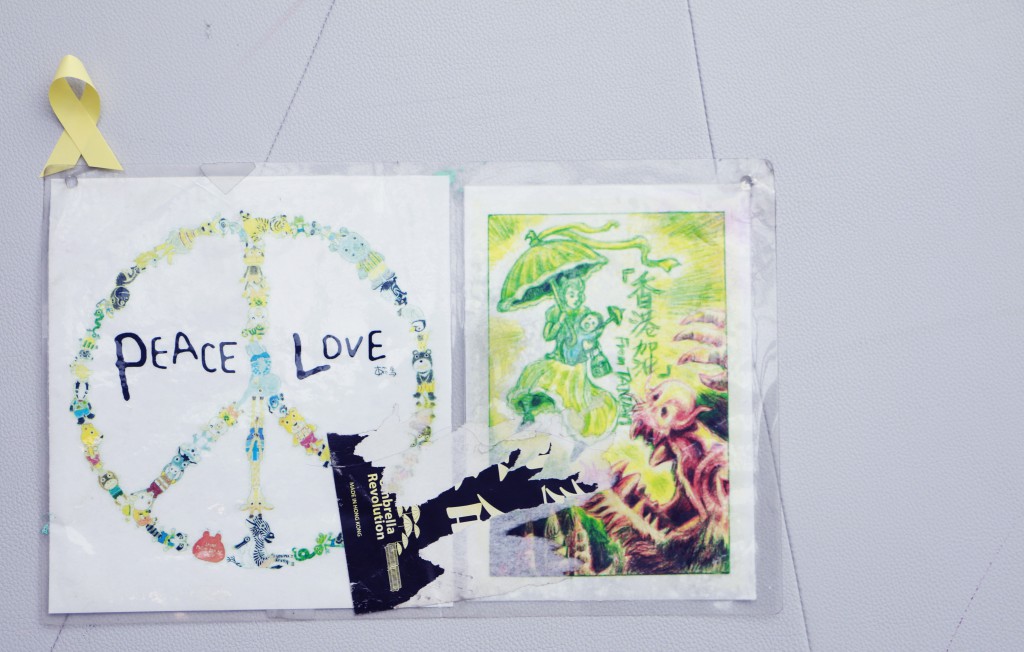

The failure to win any concesssions from the government or from Beijing has left many young people in a quandary. Some have become more radical, some have given up on working for change, and yet others are trying to seek an alternative.

For her part, Choi has given up on the government but still sees a need to take action on political and social issues. She is no longer interested in sharing her opinions online or speaking out through established channels. Instead she says she will simply act.

For example, if the government builds the proposed third runway for the Hong Kong International Airport, Choi says she would take part in a sit-in at the construction site to stop the construction work. “They [the government] will never listen to criticisms, and the last resort is to block the excavator.”

She is not the only one who believes that Hongkongers need to step up radical action.

Since the end of the Occupy Movement, young people’s anger has been directed at the traditional pan-democracy camp and student organisations as well as the government. The pan-democrats have been criticised for lacking ability and sincerity in fighting for democracy in Hong Kong.

“I won’t cooperate with them [the pan-democrats]. We are doing different things. They can do their thing, and I won’t stop them. They can go marching, they can hand in petition letters, I won’t stop them. But I will take action on my own,” says Chan Ho-tin.

Chan is a 25-year-old graduate of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. As an undergraduate, he was the convenor of a concern group which instigated a university referendum for the withdrawal of the university’s student union from the Hong Kong Federation of Students in April this year. He has chosen to stand on the frontline in many “radical” protests, including the anti-parallel trading rallies that frequently involved physical conflicts between demonstrators and the police.

Chan says Hong Kong may have reached the stage where revolution is necessary. He gives the example of Korea and Taiwan, where deaths occurred before there was democracy. He thinks that if some Hongkongers are willing to fight for their city, it is very likely there will be bloodshed. “And I think, I have to join as well,” says Chan.

The government may not be meeting the political demands of Hong Kong’s youth but is aware of their dissatisfaction. Both the administration and the pro-establishment camp have responded in various ways – on the one hand criticising young people’s radical behaviour and on the other implementing specific policies targeting young people.

In November, as the Occupy Movement was ongoing, executive councillor and a key ally of Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying, Fanny Law Fan Chiu-fun told a radio programme that her friends were so scared of Hong Kong’s young people that they were considering emigrating.

Meanwhile, the Chief Executive set up the Youth Education, Employment and Training Task Force under the Commission on Poverty. The Occupy Movement, he explained, had highlighted a need to review the government’s youth work, with particular reference to young people’s diverse needs and upward social mobility.

All this is too little, too late for Ying Cheung, a Year Four Chinese medicine student at Chinese University. Cheung joined last year’s class boycott and was in Admiralty when police fired teargas at protesters. She also volunteered at medical stations at the occupied sites. Although she says she still cares about Hong Kong, she pays less attention to news and current affairs and does not participate in any socio-political activities. Instead, she has her mind set on finding a job abroad and leaving Hong Kong for good.

“I think Hongkongers have no influence, whatever we do is useless. That’s to say this is no longer a place fit for living,” she says.

Wilson Wong Wai-ho, associate professor of the Department of Government and Public Administration at the Chinese University says the feeling of powerlessness is widespread among Hong Kong’s youngsters. Those like Ying Cheung appear to have given up while others, like Jasmine Choi and Chan Ho-tin, have become more radical because young people cannot participate in politics and the process of decision-making that affects their lives.

“[Their discontent] is because of long-simmering anger and exclusion from participation. Honestly, do you think they want to attack the government in such a fierce way? But, if they don’t do that, what else can they do?”

Wong says the end of the Occupy Movement has left some young people disorientated. Youth leaders who were once put on a pedestal have been knocked down and individual participants are left wondering how to seek a way out from the division and stalemate hanging over the city.

However, Wong believes the divisions can be overcome as they involve misunderstandings between people with different views rather than entrenched divisions between, for instance, racial and religious groups.

Dominic Ho Ka-ki and Yoyo Jiu Wai-man, students of government and law at the University of Hong Kong, share this view. Both of them are acutely aware of the polarisation in society but instead of taking sides like many young people, they believe it is better to make space for rational debate, so that people can agree to disagree.

“I dare not say that I can guard the room for rational discussion, but at this moment, I hope to be involved in this and create more room or at least slow down the rate of decline, because we should reserve room for discussion,” says Jiu.

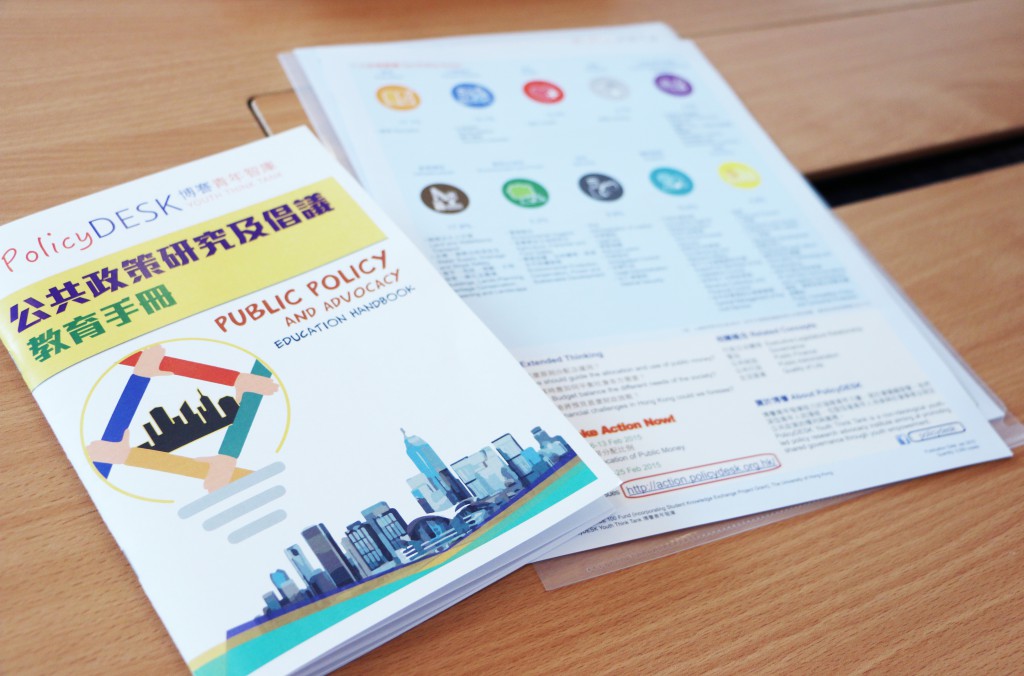

With this in mind, the pair co-founded Policy Desk, a youth-led policy research institute focused on public policy issues, or as they describe it, a think tank belonging to young people. Their work includes creating reader-friendly digests that simplify details of ongoing government consultations or important public policy issues, and presenting different views. These are posted on their website and social media pages as well as sent to schools.

After getting feedback from their readers, who are mainly secondary school and university students, the group will collect and publish their ideas and pass them onto the government.

Ho thinks that although there are already lots of heavyweight think tanks, such as the Central Policy Unit and Civic Exchange, there are not sufficient channels for young people to thoroughly approach or comprehend important social issues, let alone for them to express their ideas. In post-Occupy Hong Kong. Ho says the government will eventually have to take public opinion into account, otherwise people will continue to take radical action and hinder the implementation of public policy.

This is why he engages in this work. “You can join demonstrations, you can protest online, but you can also stay behind and do research,” says Ho.

Alan Lam Ka-leung, a member of another young people’s think tank called GeNext, also prefers to work on research and policy instead of charging on the frontline. Besides spending time on his own organisation, he also writes articles for various political groupings. These include Path of Democracy, the think tank newly-established by lawmaker Ronny Tong Ka-wah, who quit the Civic Party earlier this year.

Lam self-consciously refers to his choices as “abnormal” compared to his peers. He says the things he writes for various political groups may not reflect what he really thinks but he regularly attends their meetings and works as a volunteer for them. “I think sometimes when you observe and learn more, you can hold fast to your values, even in environments you don’t like,” Lam says.

For many of the young people who participated in the Occupy Movement, it was not just a political movement, but an experience and process in which their values were articulated and tested in unpredictable circumstances. After the movement ended without any concessions from the government, their sense of powerless and distress is palpable.

The Hong Kong Institute of Education entrusted The Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey to conduct research in February to find out the mental state of Hongkongers after the movement. Among the 1,200 interviewees, nearly half were still anxious though nearly two months had passed. The findings showed youngsters between 18 and 24 years old were the most emotionally affected. Nearly 60 per cent of interviewees from that age group were analysed as having medium to severe anxiety, and around 20 per cent were medium to severely depressed.

Yet in the face of anxiety and the sense of powerlessness, Hong Kong’s young people are trying to move on. One afternoon in late September, Varsity accompanied Jasmine Choi Yan-yan, who was denied access to the Mainland after her arrest in Civic Square, to the Lok Ma Chau Spur Line Control Point. She had heard that a friend of hers who had had the same experience successfully crossed the border a year after the occupation. Choi wanted to see if the same would be true in her case.

Eventually, it was her turn to be examined after waiting in a long queue. There were many travellers laden with bags or dragging pieces of luggage. Choi was the only one who stood there with just her Home Return Card in her hand. She waited for the official to take her card, their eyes met, and after a short pause, she walked past the checkpoint and eventually arrived in mainland China.

Her first reaction was relief. She would be able to go to the Mainland to visit her relatives, perhaps to work. But on reflection, she realised how easy it would be for the authorities to revoke her access again.

She was still powerless.

Edited by Stella Tsang