Kuomintang presence and influence have waned since 1997, but Nationalist sympathies remain alive in Hong Kong.

Reporter: Margaret Ng Yee Man,Christine Tai

Outside a two-storey house, tucked away in Zhongshan Park in Tuen Mun, some 200 people gathered in front of a memorial bust of Sun Yat-sen on October 10 to raise the flag and sing the anthem of the Republic of China (R.O.C.). Their display of patriotic fervour was to mark the annual Double Tenth Festival and, more particularly, the 100th anniversary of the Xinhai revolution which saw the overthrow of China’s last imperial rulers.

The house, known as Red House, was one of the command centres from where Sun, the man regarded as the father of modern China, planned uprisings and coups against the Manchu government between 1901 and 1911.

Through Sun and his fellow revolutionaries, Hong Kong developed strong historical links with the republican revolution in mainland China. Later, it would also have links with the party founded by Sun, the Kuomintang (KMT), or Nationalist Party. Those links grew after the ruling KMT was defeated by the Chinese Communist Party and forced to retreat to Taiwan in 1949.

The then British colony became a haven for thousands of KMT soldiers. They were first settled in refugee centres in Kai Lung Wan on Hong Kong Island. However, the colonial government decided to move the Nationalists to a more remote spot after riots broke out on October 10, 1956 when government officers tried to remove R.O.C. flags in Lei Cheng Uk. The community was moved to Rennie’s Mill, now known as Tiu Keng Leng.

This enclave came to symbolize the KMT in Hong Kong in the minds of many Hong Kong people. But it was not the only place where the KMT’s presence was felt in the colony.

Chang Chak-yan, who teaches Asian comparative politics at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, says the KMT organised many social activities in Hong Kong before 1997. The colonial government was tolerant of the activities as long as they were not too overtly political.

In fact, it did not take long after 1949 for the KMT’s influence to spread through Hong Kong society. In the early years after the civil war, the territory became a propaganda battleground between the rival governments in Taipei and Beijing.

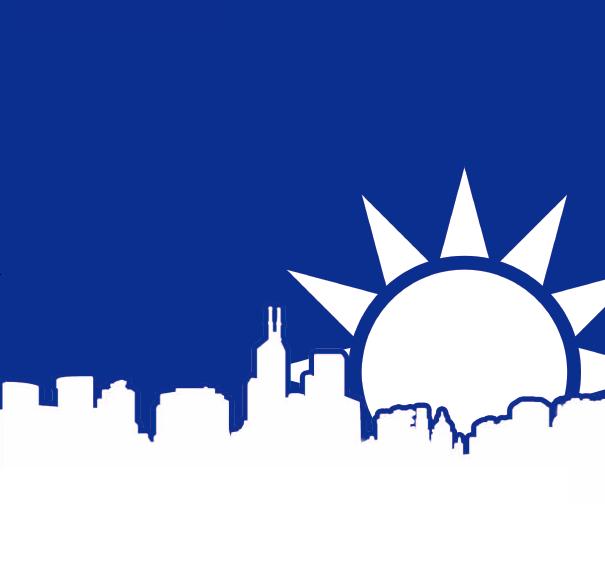

The R.O.C.’s flag symbolising a white sun in a blue sky and the red earth flew freely in the New Territories and KMT-subsidized schools like Hong Kong Tak Ming College and Chu Hai College of Higher Education were established along with pro-Taiwan trade unions like the Kowloon and Hong Kong Trades Union Council.

The government in Taiwan supported the activities of the KMT in Hong Kong and the Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission of the R.O.C. in Taiwan offered subsidies to pro-KMT schools in Hong Kong. The colonial government did not recognise the Chu Hai College of Higher Education’s degrees. So the college registered as a private university in Taiwan and its degrees were awarded by Republic of China Ministry of Education.

Many of the KMT activities were social and cultural and tended to centre around celebrations. KMT members and supporters gathered at least four times a year, for the New Year, the anniversary of the Huanghuagang Uprising (March 29), the Double Tenth Festival, and the birthday of Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek (October 31).

During these events, the Red House building acted as beacon for KMT supporters. A role it still plays today.

On the centenary Double Tenth day this year, Varsity came across 85-year-old Leung Chi-keung. Wearing a hat bearing the Nationalist party flag and waving a flag in each hand, Leung sang along loudly and with pride when the KMT anthem was played. He had brought cherished old photos along with him, which he happily showed before inviting Varsity to visit his home to look at more of his KMT collection. It had been a long time since he had last shared his story, he said.

Leung shares a small public housing flat in Tai Wo. His tiny room is cramped with KMT memorabilia and the walls are covered in old photos. Although he was born and bred in Hong Kong, Leung was one of the few Hong Kong residents who served as a KMT soldier and fought against the communists.

“I found out about the KMT military recruitment through the Hong Kong newspapers,” he said, adding that he was motivated to join the army because of poverty and his dislike for communism.

He followed the KMT army to Taiwan and fought on the frontline against the communists in Kinmen Island in 1958 before retiring from the army and returning to Hong Kong in 1967. “I may live in Hong Kong, but my heart is forever in the Republic of China,” he proudly proclaimed.

Back in Hong Kong, Leung became a member of the Republic of China Veterans’ Association for retired soldiers. “We used to have gatherings in Red House every Double Tenth Festival. We went for dinner in Nathan Road afterwards,” he recalled.

However, since the handover, the association has kept a low profile and holds fewer activities. The KMT was more active during Hong Kong’s colonial days, but even then it was never recognized as an official organization.

“Kuomintang is a mystery in Hong Kong,” says Mak Ip Sing, a Yuen Long district councillor. Mak was formerly a member of a pro-Kuomintang political party, the 1-2-3 Democratic Alliance. Mak says Hong Kongers will not openly admit their identities as KMT members due to concerns about their family’s safety and political pressure.

Mak says KMT supporters in Hong Kong were not keen on engaging in local politics. It was only in the years leading up to the handover, when Taiwan began to withdraw personnel and support from Hong Kong that local KMT supporters decided to get involved. The 1-2-3 Democratic Alliance was formed in 1994 and managed to get one legislator elected to the Legislative Council and seven district councillors.

However, Mak says the party found the going tough. It lacked human resources. It was labelled as a “rightist” party and was discriminated against by other democratic groupings because of its pro-KMT background. The party lost its LegCo seat in 1998 and disbanded in 2000.

Having been involved in politics in Hong Kong for close to two decades, Mak has witnessed the change in people’s attitudes towards the KMT. “Hong Kong people feel more and more detached from the Republic of China. The conflicts between the KMT and the Communist Party are very far away from them.” Mak says people are more interested in local politics now, such as democratic development in Hong Kong. It is predictable that the number of KMT activities is declining day by day.

Supporters of the KMT say the SAR government has restricted their freedom of expression in Hong Kong since 1997. The R.O.C. flag is no longer a common sight, even on the Double Tenth days. Although there is no law explicitly prohibiting it from being displayed, the police have removed flags from public places saying they were obstructing the streets. In October 1997, police said they were acting in accordance with the “one China” principle when they removed some Nationalist flags.

Professor Byron Weng, a Taiwanese political scientist who taught in Hong Kong in the 1980s and 1990, further explains the reasons for the decline of KMT activities. He points to the KMT’s loss of power in Taiwan. “There were eight years (from 2000 to 2008) when the pro-Taiwan independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) had the presidency and became the largest party in Taiwan. It was not possible for the Nationalists to gain support to hold activities in Hong Kong.”

Weng says that before the 1997 handover, Hong Kong people identified more closely with traditional non-communist Chinese ideology. They found it easier to identify with the Nationalists because they were not the communists. However, after the handover, Hong Kong people found it harder to identify with Taiwan. They turned instead to the People’s Republic of China because it is more powerful and Hong Kong’s economy is more dependent on the mainland than ever before.

Despite such realpolitik, the KMT still manages to keep and even gain passionate followers. Dressed in the Zhongshan suit named after Sun Yat-sen, Tang Man-kit showed up at this year’s Double Tenth ceremony at Red House sporting multiple KMT badges. Tang, who is in his early thirties, is an active member of the Hong Kong China Youth Organization. The group tries to raise public concern about issues of democracy and cross-strait ties.

“You can join and become a member of the KMT when you have a KMT existing member as your referee,” said Tang, explaining how he acquired KMT membership. Tang said he joined the party after the protest on July 1, 2003 when half a million people marched against proposed national security legislation in Hong Kong.

“I was fully disappointed by the Hong Kong political system,” he told Varsity. “Starting in high school, I read books about the Republic of China and about how history changes.”

These writings drew him to the political philosophy of Sun Yat-sen’s “Three Principles of the People”, namely Minzu (nationalism), Minquan (democracy) and Minsheng (people’s livelihood).

Tang said he believed history was being whitewashed in Hong Kong and recounted an experience he had when he visited an exhibition, “Centenary of China’s 1911 Revolution”, held at the Hong Kong Museum of History earlier this year.

It featured over 150 loaned exhibits from the Hubei Provincial Museum to introduce the background and success of the Wuchang Uprising on 10 October 1911 and its aftermath.

“But it did not talk about the establishment of the Republic of China. They did not even show one ‘Blue Sky with a White Sun’ flag. The flag was designed by Sun Yat-sen and Lu Hao-tung and came to be used as a national emblem of the Republic of China,” Tang said.

In response, the museum explained that the flag only became widely used after 1913 and there were two exhibits on which the flag was printed in the exhibition.

However, Tang still believes authorities are reluctant to review history as it will inevitably raise sensitive issues about re-evaluating the revolution and comparisons will be drawn between the regimes in the mainland and in Taiwan. He hopes students can get to know more about Sun Yat-sen’s political philosophy, be inspired by the spirit of the 1911 Revolution and incorporate its legacy in their own lives.

In a park in Tuen Mun, the flag of the Republic of China was raised and people sang its anthem, they bowed before the likeness of Sun Yat-sen. Four young people, wearing shirts bearing the emblems of the KMT, carried the flag and solemnly marched to the memorial column. In this rather remote corner of Hong Kong, the Flag of Blue Sky and White Sun on a Red Ground flapped in the wind and reminded those who cared to remember of all the twists and turns the Kuomintang has experienced in Hong Kong.