Satire channels Hong Kong people’s frustrations and shines a light on Hong Kong politics

by Doris Yu

On January 11 this year, the Queen Elizabeth Stadium was packed for a satirical magazine and website’s spoof awards variety show. Those who could not get tickets for the sold-out event gathered at various public spots to watch it live on a pay TV station.

That night, social media feeds in Hong Kong were awash with video clips and discussion posts about the improbably titled TVMost 1st Guy Ten Big Ging Cook Gum Cook Awards Distribution.

The event organised by TVMost, a multimedia website founded by the popular youth magazine 100Most, featured non-A-list celebrities performing Canto-pop parodies poking fun at Hong Kong’s social and political injustice.

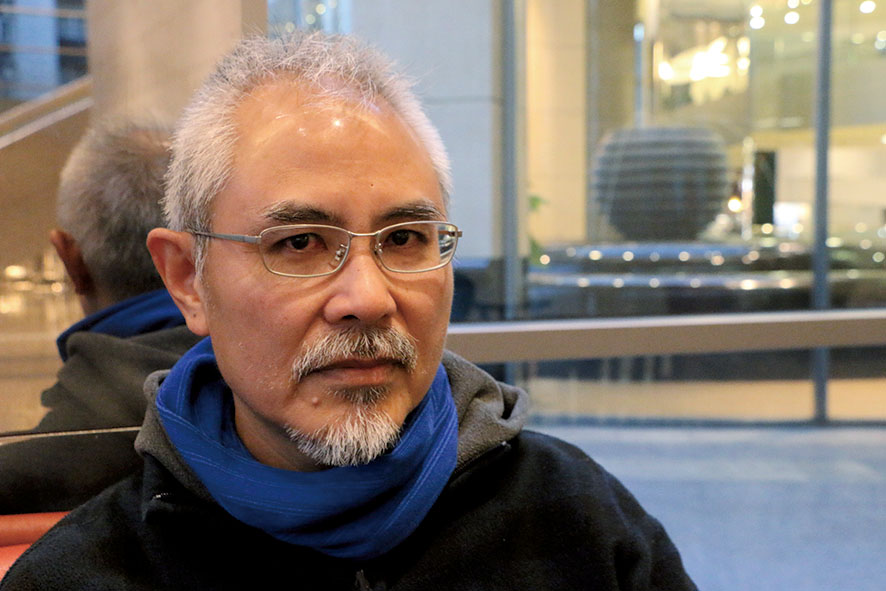

While the show was hailed as a groundbreaker, Chan Ka-ming, a lecturer at the Department of Cultural and Religious Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, says TVMost’s satire is just the latest manifestation of a decades-old Hong Kong satirical tradition. Chan says Enjoy Yourself Tonight, a popular variety show that aired on TVB Jade from 1967 to 1994, was the first Hong Kong mass entertainment show to mock social affairs by parodying songs and performing satirical dramas.

Satire is a genre of literature, graphic and performing arts which ridicules and shames individuals, companies, and most often, the government and the society

In the 1970s, The Hui Brothers Show starring brothers Michael Hui Koon-man and Samuel Hui Koon-kit sent up the capitalist classes by showing the exploitation of the grassroots by performing humorous skits and sitcoms. Then, in the 1980s and 1990s, Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s comedy blockbusters expressed Hong Kongers’ fear of mainland China and the looming 1997 handover.

“In the past, Hong Kong’s pop culture was ‘depoliticised’ – people might laugh at social issues but they never dared to touch on politics,” says Chan.

However, also during the 1990s, stand-up comedian Dayo Wong Chi-wah and RTHK television’s show Headliner started making fun of and shaming politicians and local politics. Today, it seems political satire is everywhere.

“There are so many examples of how stupidly issues and politics are handled… They dominate the topic of people’s creative work,” says Chan.

Apart from conducting research on satire and analysing it, Chan is also a practitioner who does stand-up comedy and performs satirical plays on stage. In 2012, he teamed up with Headliner’s Tsang Chi-ho for a comedy satire about the National Education controversy called Slippery when Red .

His most recent stand-up comedy, A Shaggy Dog Story was staged in May 2015. In the show, Chan uses the character of a police dog to reflect on the police force, Umbrella Movement and animal rights.

Chan says he put a lot of effort into writing the punchlines. In order to understand how the media and the public perceive the police, he collected newspapers, closely studied their content and tried to find material for jokes.

Given the subject matter of Chan’s comedy, it is tempting to assume he wants it to serve some social or political purpose, whether by stimulating debate or encouraging others to take action but he says he does not have such grand aspirations.

“For our generation, satirical work is just an ‘expression’. My drama is not intended to be inspirational. I feel satisfied when it makes people laugh and they can relate to it.”

Other young satirists are more willing to embrace an element of political purpose in their work. Post-80s designer Albert Leung Chi-yan took a risk when he quit his job at an advertising agency to set up his own design studio DDED in 2014.

At first, Leung just wanted to be free to use his design skills outside of company constraints on his creativity. But, his concern for what was going on in Hong Kong society inspired him to create animations introducing serious social and political issues in an entertaining yet ironic way.

His first video to go viral was a spoof video game featuring photographers who do battle with excreting mainland tourists. In order to win, photographers have to capture their opponents’ misbehaviour while the tourists have to attack the photographers with excretment.

His satirical output is a busy one-man operation. After he gets inspiration from his Facebook newsfeed, Leung pictures and plans the animation in his head. In order to make sure his production is timely, he draws the graphics, converts them into animations on his computer, and does the voiceovers with a microphone in his studio, all within a few hours. Then, he uploads his work onto social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube and Instagram, and replies to any comments from fans.

Leung says he never runs out of ideas because,“after the handover, there are many topics. In recent years, [Hong Kong] is getting more ridiculous.” He believes satire is a way to draw people’s attention to social issues. “We need to push people to be concerned because if people are concerned, the powers-that-be can’t act so blatantly in the future.”

DDED’s Facebook fan page now has more than 43,000 likes and Leung has also launched a line of Umbrella Movement-inspired 3D figurines and flashcards featuring cartoon figures such as “policeman”, “evil boy” who represents an occupier as seen through the eyes of the anti-Occupy “blue ribbons” and “grandpa” which resembles the cardboard cutout of President Xi Jinping holding a yellow umbrella which was seen at the occupied sites.

Instead of working to please his boss, Leung now has to impress his fans by constantly producing new content. “No post means no existence. [Regular update] is as important as breathing,” he says.

Leung has also shown that satire can be marketable. His creativity and his fan base have enabled him to make a living by producing video advertisements for companies like Mannings and promoting them on his Facebook fanpage. These advertisements are far more lucrative than sales for his figurines, which sell for HK$90 each.

Since he set up DDED, Leung has also been able to have fun with his creative freedom – his videos often contain or allude to Cantonese swear words and mock local and Chinese politicians.

However, he is worried that online satire artists will soon lose their freedom. Although the Copyright (Amendment) Bill legislation, often framed as “Internet Article 23”, has been withdrawn from the current Legislative session, he predicts there could be more restrictions on sensitive content on the Internet in the future.

“Of course, there is not much that we can do when we are fighting against authority. The only thing I can do is continue to generate good videos, use my influence and try [to make a change],” says Leung.

Like Leung, Knight, an illustrator who does not want to disclose his real name, is also worried about the the Copyright (Amendment) Bill. Knight runs a Facebook fan page with more than 24,500 followers and often mocks and criticises the Hong Kong government and the Chinese Communist Party with his illustrations and comics.

He is most proud of his cartoon strip about the Copyright (Amendment) Bill. While most netizens were still discussing the results of the district council elections last November, he was one of the earliest online satirists to notice the passage of the first reading of the bill and to produce artwork on it.

“I am glad that I fulfilled the duties of the media,” says Knight, “It is the era of ‘self-media’. Whoever has a Facebook page is a media [outlet].”

Although he is still a university student and the workload from his studies and producing content for his page is punishing, Knight does not want to give up on satire. He says he would rather give up on his studies than stop updating his page. “[The page] is my wife, my lover,” he says.

Some have criticised satire such as TVMost’s show, and Leung’s and Knight’s work for making light of serious issues by making politics “too entertaining”. The critics say such an approach may discourage audiences from taking social issues seriously and taking action.

Knight is not buying it. He says satirists neither have the responsibility to join any social movements nor to push their followers to actively join them. His only obligation is to voice young people’s frustrations and discontent with the government.

While Knight would rather support social movements from behind the scenes, Wong Kei-kwan, better known by his pen name Zunzi, hopes to mobilise the public with his political comics.

The 60-year-old political cartoonist, whose work can currently be seen in Ming Pao, Apple Daily and Next Magazine, has portrayed many political figures of the day for the past 30 years. His most notable character is “Grandpa Deng”, who represents late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in the Sino-British Negotiations. “Mr. Legislator” is another famous character which makes fun of a fictional under-qualified legislative council member.

Instead of a satirist and cartoonist, Wong would rather call himself a journalist. He believes his job is to concisely channel news, controversy and society’s frustrations into caricatures.

“Politicians tend to complicate social issues and they could not be happier if the general public does not understand them,” says Wong, “so I want to clarify and simplify events.”

Apart from producing satirical works, Wong does not hesitate to participate in social movements himself. In April 2014, his promotional poster for “civil referendum” on the method for choosing chief executive candidates was published by the New York Times. In the poster, a hand holding a red rose punctuates a book with the title “White Paper”.

Also in 2014, Wong joined the Occupy Central leaders in shaving his head to show his determination to fight for true democracy. Eventually, he followed the leaders in surrendering to police for taking part in an “unauthorised assembly” during the Umbrella Movement.

“I believe that every intellectual has the responsibility to voice their opinion honestly on social matters, and help change society to be a better place to live in. Some of them use writing, some use photos, some use music or performance art, and I choose to use political cartoons,” he says.

But while Wong believes satire plays an important role in social movements and is pleased to see more artists use satire after the Umbrella Movement, he harbours doubts about the influence of his and his peers’ work.

For instance, he says he finds it is hard to counter people’s mental fatigue and carry on encouraging the public to participate in the June 4 candlelight vigil year after year through his work. He has been doing so for more than 25 years, yet disappointingly, he does not think that an official reassessment of the bloody crackdown of 1989 is on the horizon.

“I feel powerless… All I can do is tease but I cannot change reality,” says Wong.

Edited by Zoe Tam

Learning how to tease is so important