More than two thirds of youth support localism but what does it mean to them?

by Chloe Kwan & Stanley Lam

Unlike many of her peers, 17-year-old Sunnie Hung Sum-in does not hanker after leisure and entertainment activities after school work. Instead the year five secondary school student has bigger plans. Most days she is busy organising and promoting the concept of localism to other students. “Secondary school students are the future rulers of Hong Kong. We should push them to care about the issue and build up the national consciousness of the Hong Kong nation,” she says.

It was with this in mind, that Hung and like-minded teenagers set up Studentlocalism in April this year. She says they were influenced by the Umbrella Movement and the Mong Kok Lunar New Year unrest and some had volunteered for localist activities and were impressed by Edward Leung Tin-kei and Ray Wong Toi-yeung.

Studentlocalism aims to promote localism in secondary schools and it currently has around 60 members spread over groups in 21 schools, including the prestigious Wah Yan College on Hong Kong Island and Ying Wa College in Cheung Sha Wan.

Hung and other members of Studentlocalism spend some of their free time setting up street stations and handing out independence-themed fliers to young people in areas like Mong Kok.

“I think related ideas could stay in their minds after reading the flyers, and when they read information shared online. Maybe they’ll want to know more,” she says.

She also tries to spread the message in her own school. Hung founded a localism concern group – which has around seven members – in HKICC Lee Shau Kee School of Creativity. She stuck up posters supporting Hong Kong independence all around the arts and design-oriented school and sprayed graffiti that read “Hong Kong’s Independence” in the staircase in mid-September. At first the school did not take any action.

But Hung says that after receiving advice from the Education Bureau, the school removed the posters and slogan. Earlier, in late August, the government had warned that teachers could be barred from teaching if they promoted separatist ideas in schools. Secretary for Education Eddie Ng Hak-kim said there should not be any independence activities on school campuses as the idea does not comply with the Basic Law.

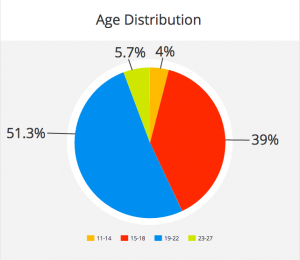

None of this has deterred Hung and it seems her ideas about localism are indeed widespread among young people. In a survey of 350 people aged between 11 and 27, Varsity looked at young Hongkongers’ views and understanding of localism.

The survey found that close to 69 per cent of the respondents said they supported localist groups, which is higher than suggested in similar previous polls.

Francis Lee Lap-fung, a communications scholar at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) is not surprised by the finding.

“In the previous territory-wide polls, localist groups might have an 8 to 9 per cent support rate. It can add up to 40 per cent if respondents are stratified from 18 to 30 years old; we can expect support rate rises with younger respondents,” Lee explains.

Asked to identify which political parties or groups are localist, 83 per cent of respondents ticked Hong Kong Indigenous. Youngspiration and Civic Passion followed with 78 per cent and 77 per cent of respondents recognising them as being localist respectively. However, only 33 per cent identified Hong Kong Resurgence as a localist group. Hong Kong Resurgence is led by the proponent of the Hong Kong city-state theory, Horace Chin Wan, who is often regarded as the “godfather” of localism.

And while Youngspiration’s Sixtus Leung Chung-hang has previously denied that Demosisto’s Nathan Law Kwun-chung, Democracy Groundwork’s Lau Siu-lai and Land Justice League’s Eddie Chu Hoi-dick are localists, 20 per cent of respondents classified Democracy Groundwork as localist and close to half identified Demosisto as localist. In fact, all three describe themselves as supporters of “democratic self-determination”.

“Whether localism equals advocating Hong Kong independence remains blurry. A year ago Youngspiration did not really mention Hong Kong independence. Society is continuously defining it,” says CUHK’s Lee. He adds that it is not just localist terminology that is ambiguous. HKTV founder Ricky Wong Wai-ki, for instance, may be pro-establishment but he is also against the current chief executive.

When respondents were asked to rate the extent to which certain incidents drew their attention to localists, the Mong Kok Lunar New Year unrest came up top, followed closely by the Umbrella Movement. These were followed in descending order by the anti-parallel traders’ protests, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee’s August 31, 2014 decision, the case of the missing Hong Kong booksellers, and the anti-National Education movement. The anti Hong Kong-Guangzhou speed rail movement and the demolition of the Star Ferry Pier and Queen’s Pier in Central ranked much lower.

When respondents were asked to rate the extent to which certain incidents drew their attention to localists, the Mong Kok Lunar New Year unrest came up top, followed closely by the Umbrella Movement. These were followed in descending order by the anti-parallel traders’ protests, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee’s August 31, 2014 decision, the case of the missing Hong Kong booksellers, and the anti-National Education movement. The anti Hong Kong-Guangzhou speed rail movement and the demolition of the Star Ferry Pier and Queen’s Pier in Central ranked much lower.

Lee says people turned to “localism” after they realised the long-held principle of “peaceful, rational, non-violent” local protest and civil disobedience did not work in achieving their goals.

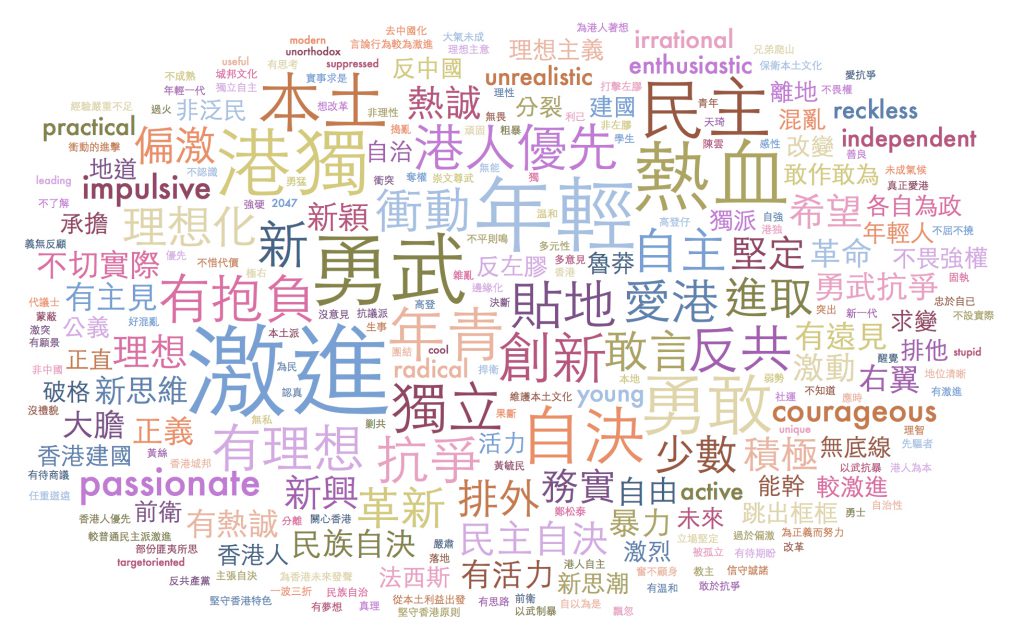

When respondents were asked to offer terms to describe how they saw localists, some common terms were “passionate”, “radical” and “pro-active” as well as “a hope”, “ambitious” and a “way out” for Hong Kong. The descriptions express young people’s disatisfaction with Hong Kong’s current sitation and their hope that localism can provide a path for the future.

These sentiments are also finding their way into Hong Kong’s popular culture such as films, music, mash-ups and memes, which both reflects the social mood and reinforces it in the audience.

Eric Ma Kit-wai, a CUHK professor and expert on Hong Kong identity and popular culture, says the prevailing social mood is best expressed through popular culture, which can be dramatised and visualised.

“A series of social incidents, such as the Umbrella movement, the anti-Guangzhou-Hong Kong high-speed rail movement, the anti-national education movement and so on, have accumulated the negative emotions of the youth… With such factors, producing the localist songs and movies is a way to project their emotions,” says Ma.

Ma believes this is the reason why the film Ten Years, which can be seen as a product of localist culture, is so popular among youngsters. Studentlocalism’s Sunnie Hung says she is affected by films and has watched the dystopian film three times. “I think the scenes [depicted in the film] are becoming closer and closer to our reality in Hong Kong. It’s not an exaggeration at all,” she says.

Ho Cheuk-tin, a filmographer and founder of the political satire group Mocking Jer, says the group set out to spread local consciousness (本土意識) through producing parody videos during the Umbrella Movement. Their first video, uploaded on YouTube in December 2014, is a derivative work based on the 1990s local gangster movie Teddyboy. It mocks excessive police use of force against the Occupy protesters by parodying “black police” as gangsters.

“There were too many junk videos from Hong Kong Youtubers like how to date girls and eat noodles. I quite despised them so we started Mocking Jer. Filming is what film school graduates are good at,” says the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (APA) graduate.

Ho and his fellow APA graduate Neo Yau Hok-sau made more videos about the Umbrella Movement after the success of the Young and Dangerous parody. Then last year, both had a chance to express ideas of local consciousness in Ten Years.

“During the production of Ten Years, I figured Hong Kong independence is possible,” says Ho who was the assistant director in one of the film’s vignettes, Self-immolator.

The segment starts with a young social movement leader who is imprisoned for violating Article 23 of the Basic Law and dies after a hunger strike in jail. One of his supporters then sets themself alight outside the British Consulate to draw attention to the independence idea.

Ho says many actors shied away from the production because of the theme of independence. “Many ran away when they saw the script in casting,” he says.

Banned in the Mainland, the movie was awarded best film of 2015 at the Hong Kong Film Awards. Ho thinks it heralds the rise of local consciousness-themed movies and shows that films with local themes have influenced people’s views and the public discourse.

Film is not the only medium being used to boost local consciousness in the city. Lyricist Leung Pak-kin aims to “awaken” society through popular music.

Although he is not a “hardcore localist”, Leung has been trying to create resonance with local issues through his lyrics. He started writing lyrics with a local rock band Kolor seven years ago.

“Rock ‘n’ roll has its origins in politics, like the American rock band Rage Against the Machine. Bands should express things that have to do with the society, complementing singers who fear being banned by the Mainland,” he says.

Leung’s lyrics for Kolor cover various local issues such as parallel trading, filibustering in the Legislative Council and the wealth gap. He believes Cantopop should have a wide scope, rather than be limited to the senitmental love songs that dominate the local industry.

As a child of the 1970s, Leung has witnessed changes in the extent to which pop songs can influence society. Sam Hui, known as Hong Kong’s “God of Songs” produced Cantopop songs with strong local themes, such as Could Not Care Less About 1997, but Leung says people did not pay much attention to the issues in the songs back then.

“As we actually feel the pain from the pressing issues now, songs with social themes will receive a much wider response,” Leung says.

Leung says it is interesting to see how writer and audience play their part in a game to create meaning. The lyricist may use similes and metaphors in the songs, while the listener will deconstruct these to interpret the lyrics.

“Like Endless by Supper Moment is now a song of social movement while A Brighter Future by Beyond is like the anthem of Hong Kong. Every song has its destiny,” says Leung.

Like other locally conscious creative artists, he hopes his work will spread a message about Hong Kong’s values and have resonance with the young people who will help shape the city’s destiny.

Edited by Tiffany Tsim

Correction: An earlier version of this story said we surveyed 504 people, of these there were 350 effective responses. All figures shown referred to the 350 respondents and the copy has now been amended to show this. We apologise for any confusion.