Hong Kong’s privately owned public spaces are hard to access, poorly designed and barely regulated

By Eric Park & Zoe Tam

On Johnston Road, in the heart of Wan Chai, a cluster of immaculate, four-storey heritage houses stand out from the nearby high-rises. The buildings date back to 1888 and were a classic example of Chinese tenement buildings or tong lau once common in southern Chinese cities. One of them housed the famous Woo Cheong Pawn shop which provided the inspiration for the name of the high-end bar and restaurant now housed in the building, The Pawn. The building’s other tenants are upscale retail shops.

Not many people know that the building has a roof garden where anyone can go without paying a cent. Off the main street, an unassuming side door leads to a lift with access to the top floor of The Pawn where visitors can access a roof garden overlooking Wan Chai. A small sign posted next to the lift shows the roof garden is opened to the public from 11a.m. to 11p.m. every day.

When Varsity visited the roof garden, it was decorated with lots of potted plants. However, around a third of the area was taken up by restaurant equipment such as large refrigerators and stoves. There were also fire-extinguishers that were past their expiry date.

Ms Chung, who works nearby was visiting the garden with her friends. They had heard it was a public open space and decided to check it out during their lunch-break. They were disappointed with what they found. Ms Chung thinks the garden is a bit messy and poorly-managed. “[The government] should send some people to check this place regularly, otherwise people will just take it over,” she says.

In fact, this space illustrates the confusing boundaries between public and private space in Hong Kong. The Pawn was restored by the Urban Renewal Authority (URA) in 2005 at a cost of HK$15 million. It was co-managed by the URA and a private property company until March 2014, and is now solely owned and managed by a private developer, K. Wah International.

Most people thought the roof garden was a private space that could only be used by restaurant patrons until media reported that the roof garden was designated for public use under an agreement between the government and the URA. In a written reply to Varsity, the URA said it had required the developer to open the roof garden for the public’s use in the lease. But the roof garden was not stated as a “public space” either on the land deed or the master layout plan which was approved by the Town Planning Board.

In March 2012, there were reports that the property management company of The Pawn called police when they found people having lunch in the garden, which violated the venue’s rules. The URA responded to media enquiries by saying the roof garden is a “private open space” instead of a “public open space”.

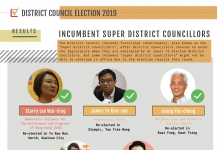

The Pawn’s roof garden is not the only place that shows the poor management of open spaces for public use in Hong Kong. The heated controversy over public space in the city first emerged in 2008 when local media discovered Times Square, a shopping mall in Causeway Bay, restricted public access to space on its ground level, which is legally considered public space. The incident triggered a debate about the management of privately owned public space in Hong Kong.

The term privately owned public space may sound like an oxymoron. It refers to areas within private properties that are legally required to be open for use by the public. In Hong Kong, the policy of creating public open space in private developments (POSPDs) was introduced in 1980, with the aim of optimising land use for better urban development. According to the Lands Department and Buildings Department, there were a total of 56 POSPDs in Hong Kong as of June 2014.

Since the Times Square controversy, the government began to re-examine the provisions of POSPDs and to collect information about the sites across the city. In 2011, the Development Bureau issued the Public Open Space in Private Developments Design and Management Guidelines in response to this issue. The guidelines provide suggestions on the design, facilities and greening areas of POSPDs. But they are not legally-binding which may limit their effectiveness in managing POSPDs.

For instance, some POSPDs are hard to access, poorly-maintained and have opening hours shorter than the 13-hour requirement laid out in the guidelines. According to a survey conducted by the Audit Commission in October last year, some POSPDs have extremely low patronage rates because of irregularities such as locked gates, closure of passenger lifts and obstructed access. The survey highlighted one case in which visitors were required to climb 200 steps to reach the open space.

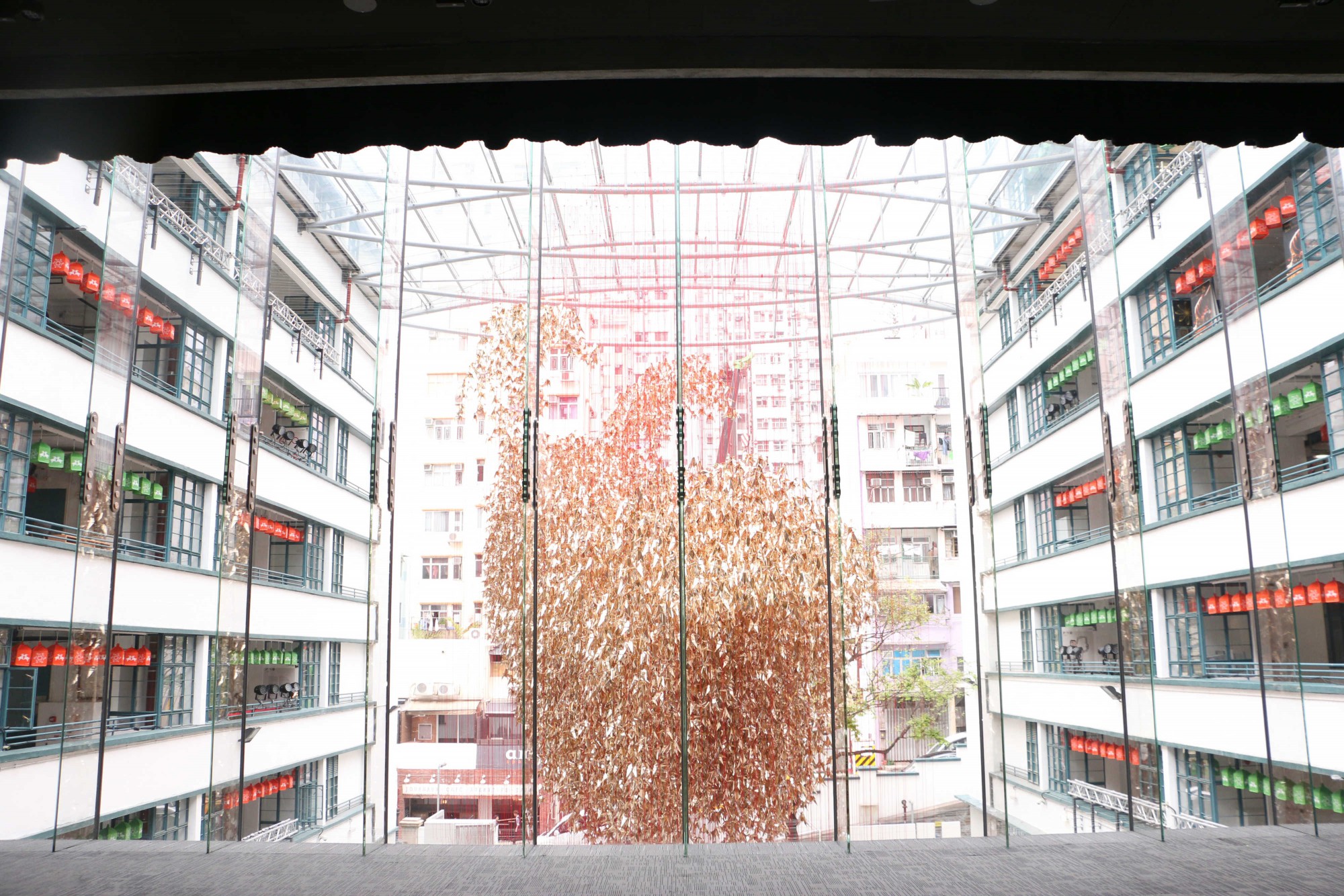

Central and Western district councillor Ted Hui Chi-fung agrees that due to bad design or poor maintenance, some POSPDs fail to attract members of the public to enjoy them. PMQ, the former Police Married Quarters in Central, is one example.

The PMQ revitalisation project, which started in 2010, transformed the two previous police residential blocks, built in 1951, into a creative art hub. The government said there should be three main objectives in the layout for the PMQ development, one of which was “provision of local open space”. When it consulted the Central and Western District Council on its plans, the developer stated there would be three open space areas in the new PMQ. However, Hui says the locations and usage of the open space areas were not stated clearly in the proposal.

When PMQ officially opened in June last year, Hui was disappointed to find that the three open space areas were not user-friendly at all. They include the lower entrance of PMQ where people can sit on benches and watch visitors coming in; a small space located at the back of the building’s courtyard where people can sit and relax, and the fourth floor Plateau which serves as a footbridge to connect the two blocks of the building.

Hui thinks the three open spaces are far from satisfactory as they are either too small for people to organise activities in them or are unnoticed by most visitors due to their inconspicuous locations. “When the developer [of PMQ] showed us the number of open spaces, we thought it would be enough but they ended up in some unnoticeable areas or corners. I think it’s a bit unacceptable,” he says.

Alfred Ho Shahng-herng, a local urban researcher who specialises in city planning, says private developers agree to include open spaces in their buildings because they can gain tangible economic benefits from doing so. Under the Buildings Ordinance, developers can be granted extra gross floor area (GFA) if they create open spaces for public use in their buildings. In other words, it is a way for developers to build higher buildings.

“Imagine if there is no bonus [GFA] as incentives, [private developers] will use every inch of the land instead of providing open spaces to the public,” says Ho.

Ho points out that one of the most common types of POSPD in Hong Kong is the podium garden found in residential buildings. But very often people are unaware of these public spaces because they are located inside residential buildings – people may think they are privately-owned. “Because the public can’t tell whether the space is private or not …it creates a problem that the developer may privatise the space,” Ho says.

Another contentious case involving the management of POSPDs is Metro Harbour View, a private housing estate in Tai Kok Tsui. The podium garden located on the fourth floor of Metro Harbour View is considered a public space under the land lease. However, nearly all the residents of Metro Harbour View thought the garden was a private space until 2008 when local media revealed it was a space for public use.

In 2011, the Development Bureau proposed to exempt the podium garden from being a public space as it is not easily accessible to the public. This requires the consent of the Area Committee, which is formed by representatives in Tai Kok Tsui, the District Council, the Town Planning Board and the Lands Department. The Area Committee raised objections and the issue remains deadlocked up till now.

Yau Tsim Mong District Councillor Patrick Lau Pak-kei, who also lives in Metro Harbour View, says both the government and developer of Metro Harbour View should bear responsibility for the problem. “To those who don’t live here, the podium garden is inconvenient to access as it’s located on the fourth floor of the estate … the location [of this POSPD] is unreasonable,” he says. “The developer has responsibility too. Many residents felt deceived because they were not informed clearly [that the podium garden was a public space] when they bought properties.”

Such conflicts over privately owned public spaces occur for many reasons but Kenneth Chan Kin-wang who works for an architectural firm and is a project manager of the non-profit organisation, Hong Kong Public Space Initiative (HKPSI), says the main problem lies in miscommunication among different sectors – the government, developers and property management companies.

Chan says the root cause of the confusion and disagreements regarding public spaces lies in Hong Kong’s property management culture. He says developers commonly hire property management companies to control and oversee their real estate. But these management companies may not understand the concept of public space well.

“The property management companies have low understanding of what public space is … they only want to keep [the areas] safe and avoid all the risks. They are not trained for [managing] public spaces,” says Chan. He adds this explains why there are usually many rules in parks and other open spaces in Hong Kong.

For Chan, good public spaces bring people from all walks of life together. Ideally, such a public space should be accessible and highly visible to everyone, and be comfortable and engaging. He thinks nearly half of the POSPDs in Hong Kong are unsatisfactory in terms of location, environment and facilities.

Public spaces are essential for creating a balanced urban life for people living in cities. They are spaces for people to unwind, gather and interact with each other. In a city as small but densely packed as Hong Kong, public spaces are very valuable. Both government and the private sector should put more thought into planning and designing genuinely user-friendly public spaces. And authorities should regulate the management of privately owned public spaces in order to make Hong Kong a better place to live.

Edited by Yan Li