South Koreans show support to Hong Kong as they recall their own memory of struggles

By Eve Lee & Fiona Cheung

Two hundred people in black marched from Seoul City Hall to the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in late November in support of the Hong Kong anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (anti- ELAB) Movement. They chanted slogans and held banners in Korean, English, and Chinese that read “We support Hong Kong Resistance”.

Han Ka-eun, a 23-year-old student from Ewha Womans University and a member of Workers’ Solidarity, was one of the protestors in the rally.

“We distributed leaflets to explain Hong Kongers’ five demands to Koreans and tourists in the streets,” Han says.

“Korea has a history of student movements, so it is natural for Korean students to sympathize with Hong Kong students and fight for their human rights,” says Han. “I stand with Hong Kong because their demands are fundamental human rights. And we believe the five demands are right,” she adds.

Photo courtesy: Jun Sangjin

Hong Kong protests have taken the globe by storm for their fight for freedom and democracy. The controversial amendment to the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance proposed by the Hong Kong Government in February in 2019 sparked a public backlash. Hundreds of protestors flock to different districts in Hong Kong as the anti-ELAB Movement continued with the five key demands – withdrawal of the bill, the investigation into police brutality and misconduct, retracting the classification of protesters as “rioters”, amnesty for arrested protestors, and dual universal suffrage.

Reminiscence of South Korea’s Gwangju Uprising

South Korea has its own bloody history of democratic movements in the past few decades after the Korean War in the ’60s. Kim Hyun-sook, a 57-year-old docent of the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, shares her memories of the Gwangju Uprising in 1980 that she witnessed as a high school student.

Kim says she was on the train with her friends on May 18, 1980. “Through a window, I saw a young man with a soldier. He was bleeding, and he kneeled down next to a soldier,” Kim recalls. “But he didn’t seem afraid. He looked firm and strong,” she adds.

“A group of beaten demonstrators was lying on the ground and the soldiers were stepping on their back on May 19,” Kim says. “On May 21, my mom said a commerce centre was full of corpses in coffins,” Kim continues, “And the centre was overwhelmed with a smell of dead bodies and sickening odor.”

“It saddens me to see citizens of Hong Kong getting hurt like what happened in Gwangju,” Kim sighs.

Lim Ju-wha, representative of Gwangju Welfare Human Rights Research Institute and Amnesty International Korea 60group, says the recent social unrest in Hong Kong is similar to the Gwangju uprising in the aspect that it is a violent physical confrontation between the authorities in power and the citizens.

“In both Gwangju uprising and the anti-extradition bill movement, there is the suppression of democracy. Freedom of speech is violated and police officers do not face investigation for their brutality against protesters in Hong Kong,” says Lim.

Lim observes how history repeats. “National violence brings posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to all past, present and future generations,” says Lim. “The South Korean government is helping those who are still suffering from the trauma of the Gwangju Uprising,” she adds.

“To help prevent the repeat of Gwangju history, some South Korean students have stood up to fight with Hong Kong,” Lim says, “And this is also why people in Gwangju support Hong Kong as well.”

South Korea’s struggle to democracy — Gwangju Uprising

Chun Doo-hwan, a former South Korean Army general, began his authoritarian rule with a military coup on December 12, 1979, after the assassination of the former president, Park Chung-hee.

The military junta then decided to resume martial law, which was imposed previously by other dictatorial leaders, in early 1980. University students began to protest, demanding immediate democratization and calling for an end to martial law.

In response to the protests, on May 17, 1980, the government extended martial law to the whole country and arrested opposition figures, dissolved the National Assembly, closed all universities nationwide and banned all protests.

In defiance of suppression, a massive protest, the Gwangju Uprising, ensued in the city of Gwangju. Intense clashes between university students and the military government took place outside the front gate of Chonnam National University in Gwangju from May 18 to 27, 1980. The movement grew with the participation of civilians and won against the army on May 21, 1980. But the retreated army attacked the city again in the early morning of May 27, 1980, ending the uprising in a pool of blood. Hundreds were killed and injured.

The uprising failed to achieve what it had hoped for but remembered as one of the most significant events in South Korean history of the democratic movement.

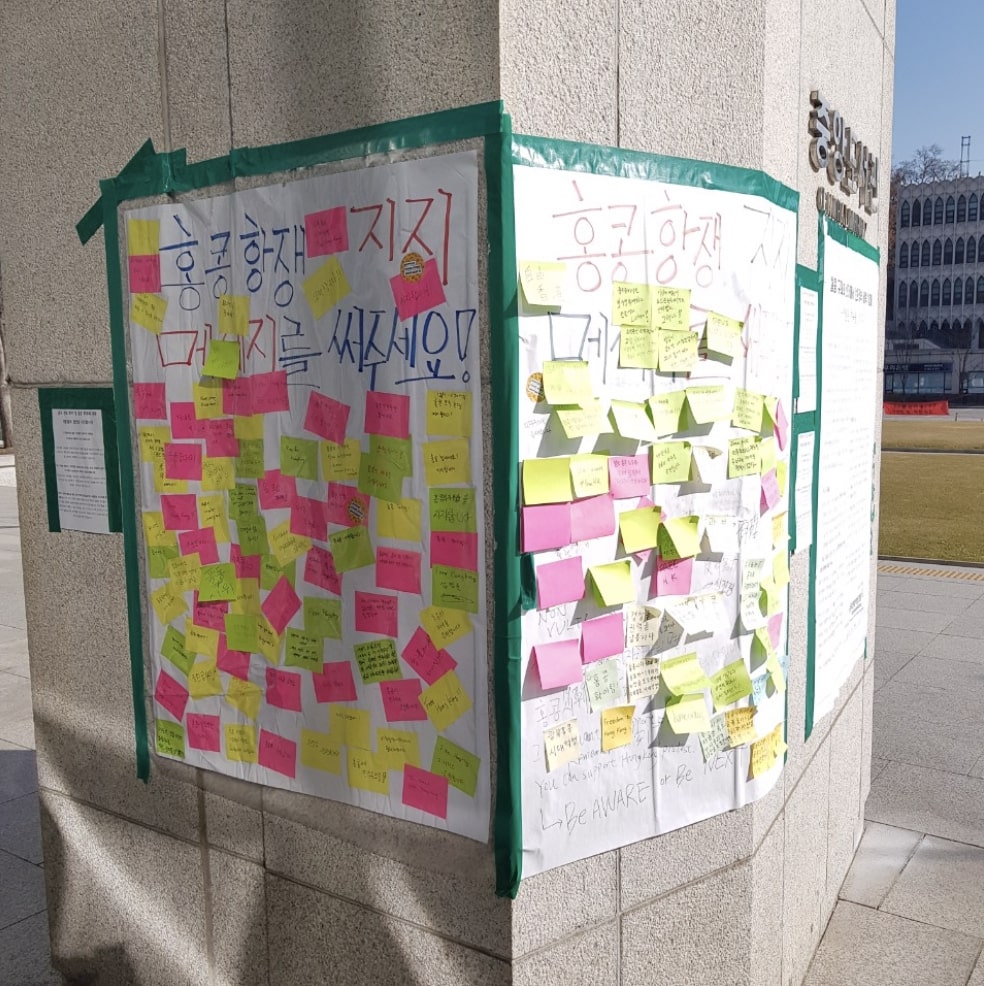

Lennon Walls on campus

Apart from joining rallies, some South Koreans supporting Hong Kong’s democracy movement have also set up Lennon walls, mostly on campus, to encourage Hong Kong students studying in South Korea.

A student organisation from Yonsei University collected encouraging messages and posted them on Lennon Wall from November 20 to early December in support of the Hong Kong protests.

“We received a letter of support for Hong Kong protest from Bae Eun-sim, mother of Lee Han-yeol. Lee died after the June Democracy Movement of 1987,” members of the organisation say. “We posted the letter on campus and recited it during the assembly on December 8 to bring more support.”

“The saddest thing is that the students get hurt and die during their fight. I hope no one gets hurt anymore […] I sincerely hope for the victory in Hong Kong”

Bae Eun-sim, mother of Lee Han-yeol

Lennon Walls in South Korean universities

Lennon Wall originated from Prague represents resistance against the communist government. The first Lennon Wall in Hong Kong was set up outside the Central Government Complex during the 2014 Umbrella Movement. The mosaic walls of post tips sprout throughout the small city with the escalation of the anti-ELAB Movement in 2019.

South Korean students who support the movement have also set up Lennon Walls across different university campuses in Korea. Some notes and banners were, however, damaged — especially those printed with “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of our time” in Chinese, a slogan commonly used in the movement. Conflicts between individuals and activists occurred.

“Maybe it’s because there is no such thing in Mainland China, so some Chinese students don’t know they shouldn’t do that,” explains Kiki, a 20-year-old student studying management at Korea University who refuses to disclose her full name.

Despite strong resistance from Chinese students, a group of ordinary Korean citizens created a Facebook page, “Hong Kong Protest Lennon Wall in South Korea”, as a safer platform to express opinions and support the movement.

The Facebook page administrator, who hopes to stay anonymous, says the page also aims to arouse public attention of the issue with the use of the social media platform.

“It is a direct threat to our freedom of speech,” the administrator says. He describes the vandalism act as “disrespectful” and “unacceptable”.

While condemning vicious attacks of the physical Lennon Walls, the administrator stresses that they are not against any nationality and believes no discriminatory comments should be posted.

Plights for giving assistance to Hong Kongers did not occur only from individuals but also from authorities.

Hankuk University of Foreign Studies issued a notice to forbid students from posting “political” posters to maintain orders on campus in November. Several other universities implemented similar measures.

In the incidents of authorities removing Lennon Walls on university campuses, speculations about pressure from China were aroused. “Along with the case above, many speculated that part of the problem, if not the only, was because of their dependence on the Chinese students’ tuition fees,” the administrator from the online Lennon Wall says.

Students immediately responded to the measure and regarded it as further diminishing South Korea’s freedom of speech.

These students involved felt they were not only fighting for democracy in Hong Kong but also defending their own freedom to speak.

The administrator says, “Some South Koreans know how challenging it is to make democracy live up to its name. Hence, they are able to better relate to conflicts in Hong Kong.”

An internal Chinese affair?

“It is a big encouragement to us,” says Joey Siu, external vice-president of City University of Hong Kong Students’ Union.

Siu believes the current situation in Hong Kong is an international issue– it influences the interest of stakeholders around the globe and the relationship between different countries.

“Their support also reflects their opinion to their own government,” says Siu. “Apart from supporting the Hong Kong protesters, it puts pressure on their government to respond to the Hong Kong issues and stand up against China’s human rights violations,” Siu explains.

Photo courtesy: Kiki

There, however, are others who think otherwise. Kiki, a student studying management at Korea University who asks for anonymity, believes that Korean students should not interfere with Hong Kong affairs.

“I think what’s happening in Hong Kong is an internal affair of mainland China,” she emphasizes, “there should not be foreign interference.”

“We have the right to talk”

“People should be able to talk about political issues freely,” an administrator of an online organisation, Hong Kong Protest Lennon Wall in South Korea, says.

The administrator, who declines to reveal his full name, believes “We have the right to talk about politics of any country and it is not an act of challenging their sovereignties.”

“Hong Kong problem is not just a ‘China’ problem; it’s of all humans, and of us” states the introduction from the Facebook page of the online organisation. The administrator and members of the platform consider themselves the same as Hong Kong people who are experiencing a political and humanitarian crisis.

“We hope to bring change for democracy,” members of the Yonsei University Students who support the Hong Kong Democratic Resistance say, “Democracy, in which normal citizens can make their own decisions in their daily encounters. That is what we want.”

The student concern group explains their plan for the coming semester in March.

“We will try to enhance our solidarity with the Hong Kong civic organizations to acquire more information about the movement,” members of the organisation say, “If there is obscure information, we will debate internally and externally to dig out the truth.”

Koreans want more media coverage on Hong Kong

In South Korea, news outlets covered the anti-extradition bill movement in their headlines when violent clashes occurred across university campuses in last November. Reporters deployed to Hong Kong were equipped with bulletproof waistcoats.

Kim Jimin, a third-year university student studying Spanish at Kyung Hee University, thinks South Korean media updates news about the social unrest constantly but not in a thorough manner.

“It is dubious. Some people think the South Korean media is being censored by pressure from pro-China groups,” says Kim. “I think many Koreans are aware of the recent incidents in Hong Kong but not the important details of what Hong Kongers are actually fighting for,” she adds.

Members of Yonsei University Students who support the Hong Kong Democratic Resistance agree with what Kim says about South Korea’s biased media coverage.

“We ask Korean media to provide the public with in-depth reports that explain the root causes of the Hong Kong protest and its significance,” they say, “we would like to know the change in the social climate of Hong Kong after the 2019 Hong Kong local elections.”

Table of incidents around Lennon Walls in Korea

| Where? | What happened? |

|---|---|

| Yonsei University | The Hong Kong protest supporting banners on campus were damaged and torn by unknown individuals in late October and early November. |

| Hankuk University of Foreign Studies | Korean students supporting Hong Kong protests said to suffer from cyberbullying by the Chinese students for their advocacy |

| Chonnam National University | Banners and Lennon Walls were damaged by individuals. |

| Hanyang University | The school transferred and archived all the notes on Lennon Wall as confrontations between Korean and Chinese students continued |

| Seoul National University | A student organization on 19 November filed a case against those who damaged the Lennon Wall |

| Korea University | A series of cases were reported about damage and preservation of Lennon walls. Korean student activists were reported to be harassed by some Chinese students for supporting Hong Kong protest. |

| Myongji University | A fight broke out between Chinese and Korean students after the Chinese students tried to damage posters on Lennon Wall on 19 November 2019 |

Edited by Soohyun Kim

Sub-edited by Tiffany Chong