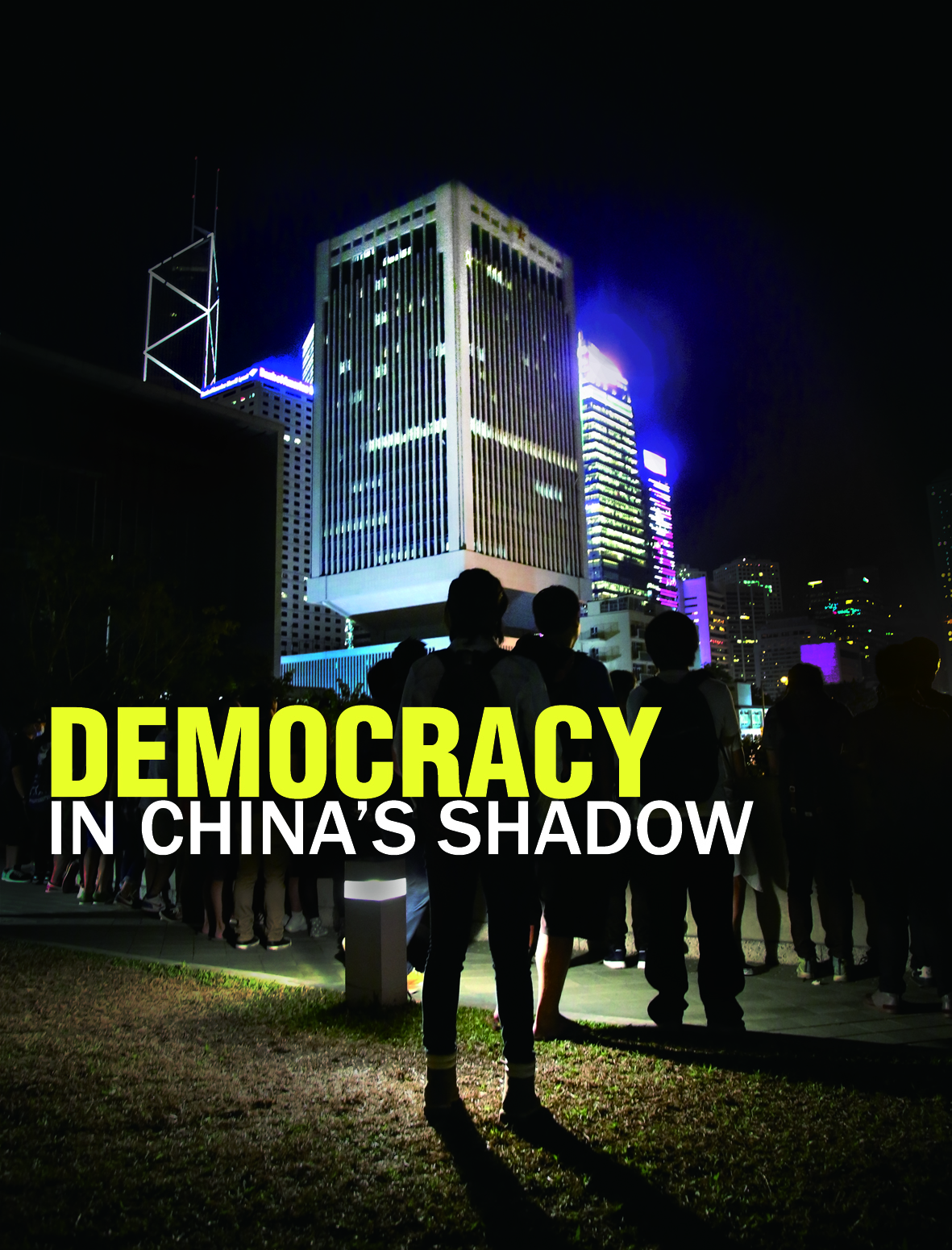

What can Hong Kong and Taiwan learn from each other in quest for democracy?

By Angel Liu and Stella Tsang

On the night of March 18th this year, student protesters in Taiwan broke through police cordons, climbed over fences, stormed into the island’s lower house of parliament, the Legislative Yuan, and occupied it. They were protesting against a trade pact with China, which they said had been passed without sufficient deliberation and due process. The occupation grabbed news headlines, and lasted for almost a month.

The movement, which became known as the Sunflower movement after a supporter brought bunches of sunflowers to symbolise the need to let the sunlight shine into the “black box” of the trade pact, found many sympathisers in Hong Kong. Slogans shouted by Hong Kong’s Sunflower movement supporters included “Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow Taiwan” and “I am a Hongkonger. Taiwan, please step on Hong Kong’s corpse and contemplate the path you want to take.”

(Photo by Wu Hsiang-Yuan)

The idea behind these slogans was clear. China’s former paramount leader Deng Xiao-ping devised the concept of “One Country, Two Systems” in 1978 to allow Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan to maintain their own systems of governance as a path to reunification. As a condition of the British handover of sovereignty to China, Hong Kong was promised 50 years of a “high degree of autonomy” under the One Country, Two Systems framework. The Special Administrative Region was meant to be a shop window for Taiwan, a blueprint showing the island the benefits of the path to reunification across the Taiwan Strait.

But while Beijing more or less lived up to its promise in the initial years after the handover, concerns have been raised about the Special Administrative Region’s (SAR’s) high degree of autonomy in recent years. Just this year, a brutal chopper attack on former Ming Pao chief editor Kevin Lau Chun-to was seen as a threat to the city’s press freedom. And a white paper issued by the State Council raised fears that the SAR’s judicial independence was being undermined.

“You cannot persuade Taiwan people to agree on one country, two systems,” says Leung Man-To, a professor at National Cheng Kung University’s Department of Political Science. In recent years, people from Taiwan have witnessed things that have happened in Hong Kong also happening to them.

“China brought Chinese economic factors into Hong Kong, and gradually changed the constitution of Hong Kong’s economy,” Leung says. “If you want to make money, you have to listen to me. China is using this to control Hong Kong, and so it will [do the same] to Taiwan in the future.”

Leung says the 2003 Mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) and the 2009 Cross-Straits Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (CECA) are examples that show how economic penetration strengthens China’s political control.

Hong Kong’s current political impasse over political reform and the civil society initiatives to break the deadlock through social movements and civil disobedience have prompted people to ask whether Hong Kong is walking the same path to democracy as Taiwan did in the past.

But Byron Weng, a professor at National Chi Nan University’s Department of Public Policy and Administration, says there are fundamental differences between Taiwan and Hong Kong. Weng, who taught at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in the 1990s, points out that Hong Kong is geographically adjacent to the Mainland, which would not need to use much military force to take control of the city. Taiwan, however, is separate from China and has its own army.

The biggest difference, says Weng is between the opponents democracy activists face in the two places. He says the Kuomintang lives in the shadow of the United States and as an anti-communist party they have to pretend to be democratic, whereas Beijing does not have to listen to anybody. “Beijing has a way of thinking that everything is in their hand,” Weng says.

Although he is somewhat pessimistic about Hong Kong’s future, Weng says that whether Hong Kong’s Occupy Movement is successful or not, it will have a significant impact on the city.

Despite the differences in their circumstances, activists in Hong Kong and Taiwan share an aspiration for greater democracy. As the social movements in both places have stepped up a gear, ties have been strengthened. Interactions and exchange of thoughts, strategies and people are more frequent than before.

Before the Occupy Central with Love and Peace organization stepped up its action and evolved into Occupy Hong Kong on September 28, Taiwanese activists held sharing sessions about their own experience. Chien Hsi-Chieh, chairman of the Peacetime Foundation of Taiwan and a leader of the huge “red-tide” anti-corruption protests in 2006, was one of them.

In the past, Chien says, Taiwanese police always used tear gas and water cannon against protesters and they would fight back using sticks and stones. When this kind of confrontation happens, he says, the media depicts participants as thugs and if the movement turns violent, the demands of the public are neglected. Non-violent protests, however, make it impossible for police to justify the use of force.

It seems that Taiwanese history may be repeating itself in today’s Hong Kong. The Umbrella Movement on September 28 showed Hong Kong people’s determination to fight for genuine universal suffrage through non-violent methods. The scene in Hong Kong looks strikingly similar to that in Taiwan, with police using pepper spray and tear gas to disperse the crowds. But what distinguishes Hong Kong from its neighbour across the strait is the protesters’ unwavering commitment to protesting peacefully.

Instead of fighting back, protesters used umbrellas to protect themselves and won plaudits from around the world while the police use of force was given wide media coverage.

“Hong Kong is like Taiwan in the 1980s and 1990s,” says Taiwan native Chang Tieh-chi, the editor-in-chief of Hong Kong’s City Magazine. Chang says the 1980s were a period of transformation for Taiwan, from authoritarian to democratic rule. At the same time, the people’s identity evolved from that of a colonized people into being Taiwanese.

The whole society went through a period of upheaval in which social and political polarization was constantly on display. Chang recalls he was a third year university student at National Taiwan University during Taipei’s first mayoral election in 1994. At that time, taxi drivers would hang flags emblazoned with the number of the candidate they supported on their cars. People on the street would make gestures at the numbers when they came across the taxis. “Every time it was like a clamour for war. It was like in the next moment, people would start to fight,” Chang says.

Hong Kong’s post-Occupy Central development has become a hot topic among Chang’s friends lately and he says they tend to have great expectations. But he believes that taking the path towards democracy is never easy. It is a long fight that cannot be won through holding a few demonstrations, and it would be impossible for people to not pay a price.

“The most important thing is that failure this time should not become defeatism,” Chang says. For him, Occupy Central is just a beginning and failure to get what people want at this stage does not represent the end of Hong Kong. “Hong Kong has to be prepared to enter a time of all-round fights among different groups and in different fields.”

He says if the National People’s Congress Standing Committee insists on their decision on the 2017 political reform, Hong Kong people still have to stand up and fight for their basic rights like freedom of speech and judicial independence, otherwise, these core values may be gradually eroded. “The important thing is how you create your own future. Every individual makes a little struggle in a critical era,” Chang says.

Sing Ming, an associate professor from the Division of Social Science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, witnessed the Sunflower Movement during his year-long stay in Taiwan. He says: “The most important thing within social movements is the education afterwards. We have to make people alert and widen the impact.”

He says he met many professors and scholars in Taiwan who would regularly hold seminars in coffee shops. Many people would attend the talks and engage in conversations about Taiwan’s democracy and future. Some of these conversations were later posted online. Sing says they used simple language that everyone could understand to write articles and books, and that these had a great impact on young people.

“Many of the scholars had been through the Wild Lily Movement. The reason why they were willing to contribute was that they had experienced oppression before. They understood the pain of losing freedom under an the authoritarian regime and White Terror,” Sing says.

The Wild Lily Movement was initiated by National Taiwan University students who, in 1990, staged a sit-in at Memorial Square in Taipei to fight for democracy. Demonstrators demanded the direct election of the president and vice president. This was later realised and the movement was a turning point in Taiwan’s transition to democracy.

Student-led movements have often been regarded as a vanguard of democratic change. Yip Chun Ming, is a Hong Kong youngster who is interested in social issues and has taken part in countless protests since high school. In March this year, he happened to be on a working holiday in Taiwan when the Sunflower movement started.

When asked about the difference between student-oriented social movements in Hong Kong and Taiwan, Yip answers, “I don’t think there are too many differences.”

“There are actually many good young leaders in Hong Kong, maybe even more than in Taiwan, but nobody’s supporting them,” he adds.

Yip says perhaps the most important lesson he learned inside the Legislative Yuan is that each person must work to try to persuade those around them.

“Every one of us is, indeed, a seed,” he says. Each time we meet a person, we plant a little seed inside their heart. Each seed may not amount to much, but in the end, says Yip, “there will be flower blossoms everywhere.”

Edited by Tracy Chan