How Hong Kong’s world-class public transport system has failed to keep pace with increasing demand

By Cindy Gu & Teenie Ho

As vehicles headed to and from Hong Kong International Airport on the evening of October 23, they were suddenly brought to a halt by an announcement that Kap Shui Mun Bridge and Tsing Ma Bridge had been closed. A barge collision had triggered an alarm and two hours of emergency inspection. The only road linking the airport to the rest of the city was blocked.

Thousands were affected and dozens missed their flights as all six lanes of traffic and MTR services on the Tsing Ma Bridge were brought to a standstill. Xin (who prefers not to give her full name), an accountant, recalls she got off work at 8 p.m. and planned to take the Airport Express. Instead, she took a taxi straight from Kowloon Station to the airport for her flight at 10 p.m., only to get stuck in traffic in Tsing Yi. “Had it not been for the airline agent offering me a rebooking, I would have totally been furious.”

Like many other stranded passengers, Xin thinks the MTR and Transport Department gave insufficient information and is disappointed there were no alternative means of public transport.

Hong Kong’s extensive and efficient public transport system is often held up as one of the city’s best features and indeed, the city ranked first among 84 countries in the 2014 Urban Mobility Index. The website of the government’s foreign direct investment department, InvestHK, proudly proclaims that the city provides a world-class public transport service that is “reliable, efficient and very reasonably priced”.

However, Hongkongers increasingly feel the transport system is not as efficient as it used to be. A spate of recent incidents has heightened their concerns.

Yuuji (who prefers not to give his full name) is a frontline MTR employee and founder of MTR Service Update, an unofficial information service on Twitter and Facebook run by passengers and MTR staff whistle-blowers. He says the Kap Shui Mun Bridge incident was “totally unexpected”, a rare event that only happens once every few decades. But the way it was handled highlights problems.

“Information updates on transportation availability given out by the MTR and the government were lacking, while communication between the MTR and the Transport Department was poor. Eventually passengers were the ones affected.”

Several other major incidents on the MTR took place in the same month, including a severe delay on the East Rail line due to power failure and a suspension of services on the Tung Chung line for over an hour due to a train malfunction.

A survey of 1,439 people by the Kowloon Federation of Associations last year found nearly half of the respondents thought the MTR was “doing so-so” when handling train operational incidents while more than 22 per cent of respondents were dissatisfied with MTR services as a whole. Nearly 60 per cent of the respondents thought MTR incidents happened frequently.

However, according to MTR’s Annual Report, the number of “reportable events” has dropped from 1,769 in 2011 to 1,327 in 2014. Yuuji explains these include events unrelated to the operation of the railway system such as injured passengers and malfunctioning escalators.

He says the MTR also has ways of dealing with incidents to prevent them from becoming “reportable”. “If a train is delayed for over eight minutes it becomes a reportable event…so repairs are usually carried out while other trains are still run on the same track to ‘make the numbers look better’.” This has the effect of keeping the problem train out of commission for a shorter period of time but adding a slight delay to every train on the track and affecting more passengers.

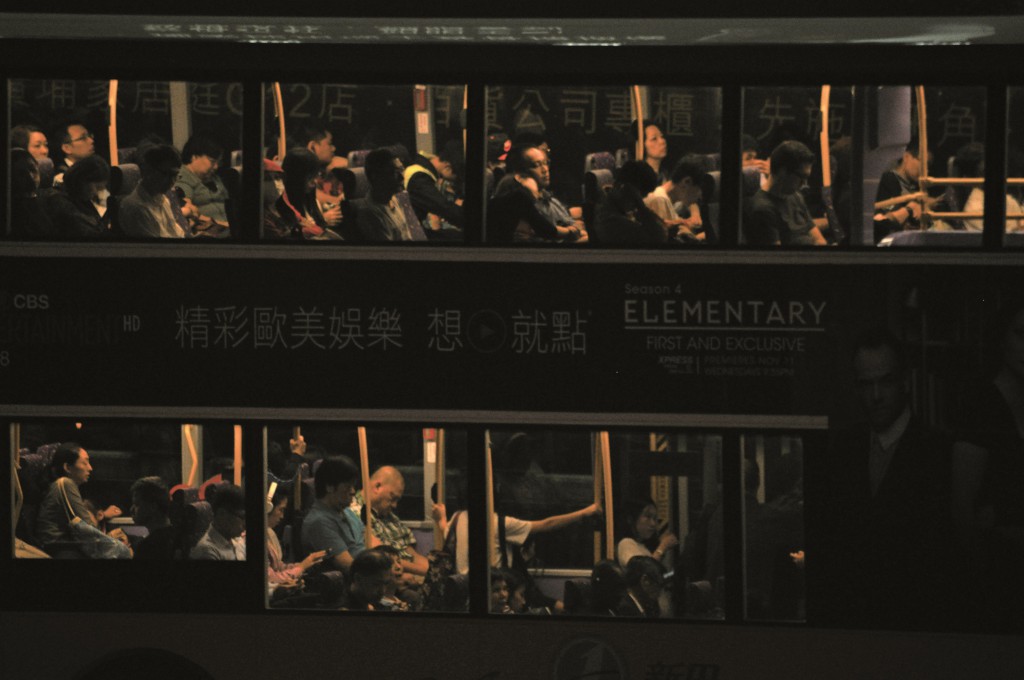

Sometimes MTR journeys may take longer because of overcrowding rather than breakdowns and signal failures.

Tunisian-born Leila Karchoud has been in Hong Kong for nearly 25 years, working as a freelance language teacher and court interpreter. Karchoud used to teach 7 p.m. classes at a language centre in Causeway Bay and would take the MTR there from her home in Tsim Sha Tsui.

One evening, she started the journey 45 minutes before class only to find a huge crowd at the interchange station, Admiralty. “I was shocked…the queue was so long I have never seen a queue like that…It was half the distance [between one platform and the other].”

Karchoud thought the crowd would clear as trains arrived every two minutes, but when the trains came they were full and only a few people could get on. She was stuck in Admiralty for half an hour and was late for work. Since then, Karchoud avoids the MTR, especially during peak hours.

Yuuji from MTR Service Update says the frequent breakdowns and deterioration of the railway system may be inevitable due to the increased demand for MTR services over the past decade.

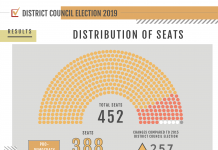

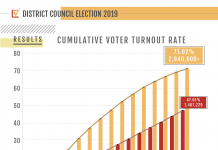

Transport Department statistics from March this year show the MTR carries about 4.62 million passengers per day, accounting for 41 per cent of public transport usage. This is a 30.5 per cent increase from the 3.54 million passengers per day recorded in December 2007, a month after the MTR merged with the Kowloon–Canton Railway.

A single journey along the East Rail line took 35 minutes in 2009 but takes 41 minutes now, due to longer waiting times to pick up passengers at stations. The higher number of mainland visitors has also led the MTR to increase train frequencies to meet demand.

The MTR currently runs nine lines with a total route length of 177.4 kilometres and 85 stations. By 2031, at least nine new lines are expected to be operating and the government expects the MTR to account for half of a public transport usage. It also says most lines will be below saturation point for some time to come. Yuuji is sceptical. “Can a railway system that is already a few decades old handle the number of passengers that reaches its record high every year?” he questions.

Those who think they can avoid delays on the MTR by taking buses may also be disappointed. Franchised bus services account for around 30.9 per cent of daily public transport usage. But some passengers are turning away from bus travel because of heavy traffic congestion in recent years.

“When I was small I thought the transport in Hong Kong was pretty good,” says Chris Lau Chun-hin, a 26-year-old newspaper reporter. “But somehow I think it is getting worse.” Lau lives in Tai Po and has to go to Kwun Tong or Hong Kong Island to report on court hearings every morning.

He originally took the bus as the bus terminal is only a two-minute walk from his home. But the traffic jams were unbearable. “It takes 50 minutes to go from Tai Po to Tate’s Cairn Tunnel, and 20 to 25 minutes more to the courts,” says Lau. The same route takes less than an hour on the MTR.

As the delay caused by congestion cannot be predicted, Lau now chooses to walk 15 minutes to Tai Wo MTR station from where it takes 40 minutes to get to Kwun Tong or Admiralty. Lau says the MTR malfunctions more than he remembers and is much more crowded than buses. “But I’d still take it because it is at least more predictable and punctual most of the time.”

Transport Department statistics show cars in urban areas travelled three fewer kilometres per hour in 2013 compared to 2003. This corresponds with a 40 per cent increase in the number of registered private cars over the same period.

Mr Yuen, a bus driver for The Kowloon Motor Bus Company, agrees that congestion is serious. He has been driving on route 74X from Tai Po to Kwun Tong for about six years. “It takes about five to 10 minutes more now. The congestion was not that bad before, and there are a lot more cars these years,” he says.

What this shows is that Hong Kong’s public transport system needs to change, says Hung Wing-tat, associate professor in the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. There have been discussions on how to improve the efficiency of the MTR and road traffic, but there has been little progress.

“For many Hongkongers, getting to the destination in the shortest time is most important,” says Hung. “For buses, passengers are dissatisfied with the long travel time caused by congestion…while for the MTR, people complain about not being able to get on the train because of too many passengers as well as suspensions and delays.”

Hung believes that as the MTR is renewing its signal system and several new lines are under construction, the situation may improve in the coming few years. By 2022, the MTR will have renewed its signal system on the East Rail line and several other urban lines. Hopefully, this will increase operating capacity and train frequency.

As for buses, Hung suggests their efficiency would be improved by developing a bus rapid transit system to alleviate congestion. Many cities such as Brisbane in Australia and Turkey’s Istanbul have introduced such systems. “There are [currently] no routes specifically for buses,” says Hung. “At least, for the MTR it can increase train frequency.”

Democratic Party lawmaker Wu Chi-wai says the government is not doing enough to improve Hong Kong’s public transport system. As a member of the Legislative Council’s Panel on Transport, he sees the issue as a complicated one.

One idea often suggested by scholars is the introduction of an electronic road pricing scheme to reduce the number of private cars on the roads. But Wu thinks this would place a burden on car drivers and it would be hard to implement the system on every major congested road.

“I agree electronic toll collection may be one of the possible ways, but it doesn’t necessarily alleviate congestion. I am personally more inclined to schemes that would offer priority of road usage to public transport like the bus rapid transit system,” he says.

Wu says the Panel on Transport will look into both electronic road pricing and a bus rapid transit system, but is not optimistic there will be progress before the current Legislative Council term ends next year.

The government does say it will consult the public next year on the possibility of implementing electronic toll collection in Central. Wu says it has also agreed to prepare a report on the possibilities of giving public transportation priority on the roads.

In the meantime, more roads are being built, including a route to connect Tuen Mun and Chek Lap Kok. The 9.1 km link is expected to be completed by 2018 and is seen as a third alternative to access the airport if accidents like the recent Kap Shui Mun Bridge happen again.

Legislator Wu says the crux of the problem is that it takes a “determined and credible government” to carry out large-scale, comprehensive infrastructure and policy reform on the public transport system. He adds that it will take time for a strong and credible administration to harness the expectations of different stakeholders. “It just isn’t what the current administration can do,” he says.

Edited by Thomas Chan