More citizens have to learn first aid to make time for the paramedics to save lives

By Agnes Lam and Kayi Tsang

Basic first aid education – first aid from ANYONE

Clad from head-to-toe in blue lycra fabric, “Anyone” is the Fire Services Department’s safety representative. The blue mannequin-like figure is featured in the department’s series of promotional videos demonstrating life-saving techniques. His videos have become a viral sensation since his debut on social media last August. Apart from being an amusement for viewers, “Anyone” has a serious message for the people of Hong Kong – Anyone can help save lives. Anyone in the city can learn to administrate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in times of emergency.

Over 5,000 cases of sudden cardiac arrest were reported outside hospitals every year, and less than three per cent of these patients survived from acute heart attacks, according to a study by the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine published in 2017. Only 29 per cent of patients having heart attacks were given CPR before the ambulance arrived.

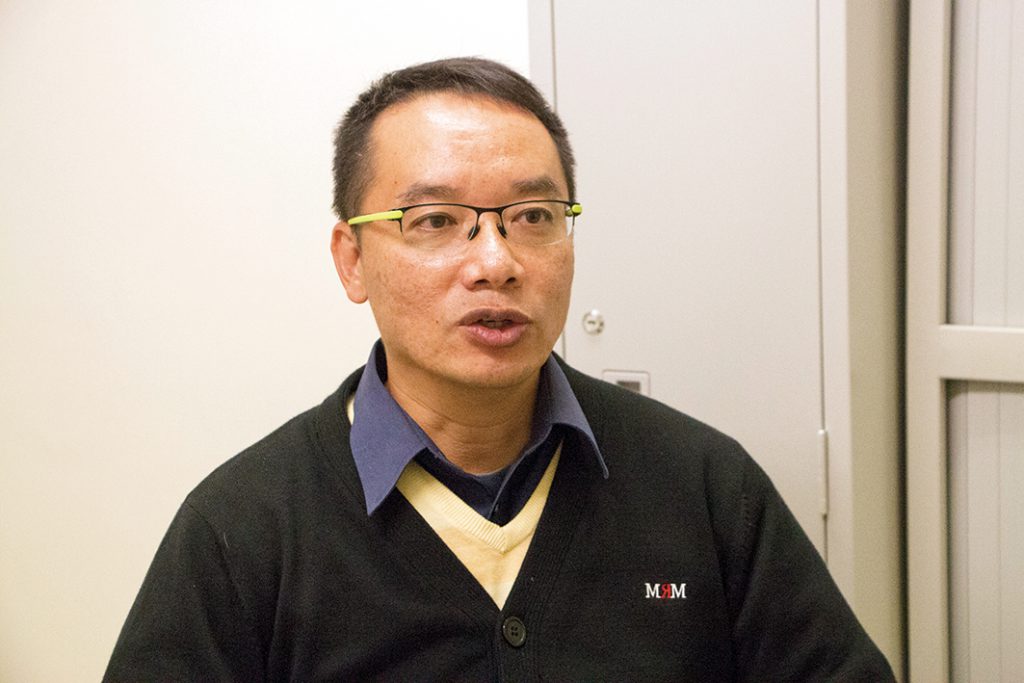

The Hong Kong St. John Ambulance (St. John) is a charitable group dedicated to promoting first aid knowledge to the general public. Chairman of the group Chung Chin-hung says it is important for every citizen to be equipped with proper first aid skills in order to help people in need when accidents happen. “First aid is the extension of doctors. It is necessary for citizens to learn this basic knowledge,” he says.

Chung believes education is the best way to promote the concept of first aid to the general public. St. John has been providing free first aid courses at both primary and secondary schools for the past few years, but schools’ responses are not enthusiastic. Among the 400 primary schools in Hong Kong, only 70 of them have enrolled in the first aid courses provided by the organisation.

“The schools tell us their students are too busy with their studies. They do not have the time to take our courses,” Chung says.

In some Asian countries such as Japan, Singapore and Taiwan, first aid training courses have been treated as regular school curriculums. Students are trained to use an automatic external defibrillator (AED) to perform resuscitation during emergencies. But the Education Bureau in Hong Kong does not require schools to provide such training for students.

Ho Dao College is one of the few secondary schools participating in St. John’s first aid training courses. Chan Kwong-kau, the teacher in charge of the first aid team, agrees that some schools may find it difficult to make time out of their busy class schedules for first aid courses. Even if they are free of charge, time is their main concern.

The solution for Chan’s school is to include first aid training in Physical Education curriculum. Every Form five student is required to undergo three hours of training during their PE classes. They are taught to perform CPR in case of emergencies.

Other than students, Chan says it is also important for teachers to learn first aid knowledge, as they have the responsibility to keep their students safe during lessons and outings.

“We organise a lot of outdoor activities and field trips. If teachers are equipped with first aid skills, they will be able to take care of our students if they get hurt,” Chan explains.

While most of the time teachers perform simple treatments like bandaging for students with minor injuries, Chan recalls he once rescued a student who fainted and lost his breath a few years ago. Chan put theories he learnt into practice and performed artificial respiration on the student. The young man was revived at the end, even before an ambulance arrived at the campus.

Legal concerns – The Good Samaritan Law

Abraham Wai Ka-chung, clinical assistant professor of Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine at the University of Hong Kong, says most citizens do not feel obligated to perform first aid treatments to others in need, as they think it should be done by medical professionals. Even they have such awareness and skills, there is currently no specific law in Hong Kong to offer legal protection to first aiders. That means a first aider could be legally liable if something goes wrong during the process.

Wai suggests that the government should implement the Good Samaritan Law in Hong Kong by taking reference from other Western countries in which legal protection is given to people who give injured people reasonable assistance. He believes introducing such a law will give first aiders a stronger sense of security when they perform emergency treatments on those in need.

“The main purpose of the legislation is to reduce their worries by stating clearly they won’t face legal problems as long as they try to save lives in good faith,” he says.

Health services sector lawmaker Joseph Lee Kok-long agrees that with the introduction of Good Samaritan Law, people with basic first aid skills will be more confident to perform emergency treatment on strangers. But Lee says the progress of legislation “is still in stage zero”. He adds that the legislative process is complicated and may take years to complete.

The Double Track Approach

Axel Siu Yuet-chung, former chairman of the Resuscitation Council of Hong Kong, says the government should adopt what he calls, ‘Double Track Approach’, while waiting for the lengthy legislation process to complete. He suggests making first aid training as compulsory courses in schools.

Siu points out patients in need of urgent treatment cannot rely on ambulance service only, as time is always crucial when it comes to medical emergency such as resuscitating a patient of cardiac arrest.

“A patient’s death rate increases by seven to 10 per cent if AED is performed one minute late. If it takes 10 minutes for an ambulance to arrive, there is little chance for the patient to be revived,” he says.

Edited by Edith Chung