From Varsity May 2010

Reporter: Margaret Ng Yee-man, Photos: Nicole Pun

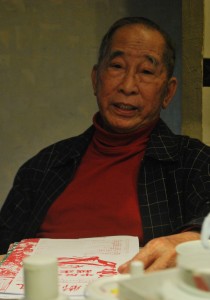

Democratic stalwart, dedicated educator, proud patriot – these are all terms that can be used to describe Szeto Wah, known affectionately as Wah Suk or Uncle Wah.

At 79, and with late stage lung cancer, Szeto has had to slow down in recent months. But he is attacking the disease with the same determination he has shown to the causes he has championed in public life.

At the time of Varsity’s visit, Szeto had started his fourth chemotherapy course. He still keeps up a daily exercise regime but the once daily swimmer has been told to quit public pools to avoid infection. Instead, he walks everyday for 45 minutes at a nearby park and does simple qigong exercises.

The home Szeto shares with his younger sister, who like him is unmarried, is compact and tidy. The walls are lined with books and hangings of thought-provoking Chinese calligraphy. As he slowly flips through leaflets produced by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movement in China, he shares memorable experiences and talks about his lifelong beliefs.

Szeto’s values were shaped by his experience of the Sino-Japanese War. When Hong Kong fell to the Japanese on Christmas Day in 1941, his mother took her seven children back to her home village in China to escape the occupation.

What should have been a three-day trip turned into a 14-day trek. “We need a strong country to escape from all these tortures.”

“Most cities we walked past had fallen into enemy hands,” he says. “The Japanese were fierce and cruel, the people were miserable. People who walked past the Japanese troops without immediately bowing were badly beaten and thrown to the ground.”

“Every morning, we brought food with us and hid in a mountain hideout, waiting for the armies to leave. By the time we returned home in the afternoon, we usually found it ransacked.”

From then on, Szeto had a keen sense of the difficulties his country faced and started to cultivate a patriotic heart. “We need a strong country to escape from all these tortures,” Szeto says.

But for him, patriotism does not mean love for any alliance, authority or leader. Instead it should be a love for fellow citizens, traditional culture and the natural environment.

In order to love fellow citizens, we need to understand their hardships. For instance, Szeto believes Hong Kong people should care about the impoverished farmers in China’s remote rural areas, and be concerned about jailed mainland dissidents like Liu Xiaobo and Tan Zuoren.

Szeto also believes that people need to know more about Chinese culture. Unless they understand the history of China, they will not be able to nurture the kind of feelings Szeto has for his country. Last but not least, Szeto says we should learn to love the country’s natural environment, rather than pollute its rivers and raze its forests.

Apart from the war, Szeto’s character has also been shaped by his family background. He is the third child of seven siblings in a family that could not afford to educate them all. The young Wah had the worst academic results and almost failed to complete his schooling.

“During the summer holiday in Primary Three, my father lost his job. Among the four children who were going to school, two had to be withdrawn,” he says. “My father chose my elder sister because of the male dominated society and myself, because my academic results were poor when compared with my brothers.”

Szeto remembers how he cried and hid himself at home on the first day of school for Primary Four when his classmates knocked on his door to ask him why he had been absent. Luckily for him, an uncle stepped in to send the children back to school.

However, Szeto says the experience changed him forever. He became much more introverted and developed a sense of inferiority.

“There is an advantage to being introverted – I have more time to think independently. I do not talk much but I can think flexibly,” he explains. “Also, the feeling of inferiority reminded me to strive for progress with determination, thus I studied hard because I did not want to lag behind anymore.”

Szeto received his secondary education at Queen’s College and developed a habit of reading books. Lu Xun is his favourite writer and his role model.

“When I was around 16 years old, I read the books of Lu Xun. He is the most influential person in my life,” he says. “I am deeply impressed and influenced, not only by his well-written articles, but also by his attitude towards life and his work. He persisted in his own principles and was fearless in the face of absolute power.”

Szeto was also moved by Lu Xun’s love for his country. “He cared about and helped the youth. He loved our country, but also saw the weaknesses of China,” he says. “Instead of blindly supporting the country, he pointed out the mistakes and dangers that existed in China.”

When he graduated from Queen’s College, Szeto embarked on what was to become a vocation – teaching.

One of his proudest achievements is the establishment of the Hong Kong Professional Teacher’s Union. In fact, it was his work with the union in the 1970s that propelled him into social activism. But what few may know is that teaching was only his second best career choice.

“When I was young, I wanted to be a sailor. I hoped to widen my scope of life and enrich my exposure. Life on a boat is quiet and therefore I thought it was a good place to read and write on my own,” says Szeto.

Szeto fell into teaching almost by chance. He had applied to study wireless transmission but he could not afford the high tuition and the two years it would have taken. Teacher training college was free. When he enrolled, he was offered the chance to study for two years in the English stream, or one year in the Chinese stream. He told the interviewer he wanted to graduate as soon as possible and chose the Chinese option.

“And he immediately said I was too eager to focus on short-term gains,” Szeto recalls, laughing.

Szeto worked in education for 40 years, nine years as a teacher and 31 years as a headmaster. Although he gives the impression of being a serious and stern headmaster, he clearly enjoys the respect of and an affectionate rapport with his students.

“My old students treat me very well. The naughtier the student was in the old days, the closer the relationship we have now.” Szeto laughs as he recalls that one of his students likened their relationship to the one between the monk Tang Sanzang and the Monkey King in the classic Chinese epic novel Journey to the West.

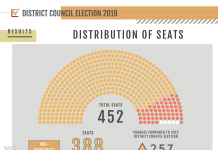

Apart from his work in education, Szeto has been a mainstay in politics. He entered the Legislative Council in 1985 and was appointed to take part in drafting the Hong Kong Basic Law in the same year. Szeto left the drafting committee after the crackdown on the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 and established the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China, of which he is chairman.

“The road to Chinese democracy is rugged, winding and long. The more we persist, the closer we are to the goal of vindicating June 4, and building a democratic China,” he says. “Vindicating June 4 is only the first step for China to move towards democracy.

The Chinese government needs to admit their fault and correct their mistakes before they arrive at true democracy.”

He adds that young people need to continue learning and know their goal if they are to continue building the path towards democracy. “The most important thing teenagers should do is to learn, either by reading books or by trying and practising. Both ways require careful thinking or you will end up with nothing.” He also urges them to set life goals, build their own characters and form their own world views.

Szeto has spent his life struggling for democracy, freedom, human rights and the rule of law. He may not have achieved all his goals but he is happy with his life. For him happiness consists of three things: “Doing meaningful things; Getting results, seeing progress in the things you have done; Making many friends who share your ideals.”

Szeto Wah is not a man for regrets, but looking back on his life, there is one thing he says he regrets.

“I used to study in an English language school, but after I graduated, I did not read any English books or speak English. That is why I have nearly forgotten all the English I have learnt,” he says.

Szeto says he will fight his illness with his “usual composure” and positive attitude.

On the wall of his sitting room hangs a framed Chinese calligraphy work with eight characters that sum up his attitude towards life: “Accept all and be great; be selfless and be indomitable.”