Surveillance, privacy and the tough choice between the privacy rights and the right to know

By Nancy Mak, Grace Liyang

Joshua Wong Chi-fung was just a 15-year-old student when he led the student group Scholarism in the campaign against compulsory national education in Hong Kong’s schools in 2012. But he already suspected his phone calls were being intercepted. “I heard strong echoes in my phone, I thought it could be wiretapping” says Wong. “I could hear my own voice and there was a lot hissing noise.”

It was not just Wong’s phone. Scholarism was disbanded last year but while it was still operating, there were constant concerns about hacking and internet theft. One documented incident took place in 2015, when the group noticed documents had been downloaded from its Google account. Scholarism confirmed that an unknown account from Nanjing called “Eastern hunting hawk” had broken into the account and downloaded personal data relating to Scholarism’s members and volunteers over the years.

Wong suspects there may have been other thefts too. “That is why during the Umbrella Movement, all the members of Scholarism, ranging from the most well-known to the least-known, were all on a blacklist and couldn’t enter the Mainland. We think that the blacklist came from the stolen Scholarism membership list,” says Wong, who is now the secretary general of the political party Demosisto.

At the time of the hack, experts suggested it may have been state-sponsored given the political sensitivity of the group. But even within Hong Kong, Wong believes there are insufficient safeguards to protect citizens’ privacy, particularly from law enforcement agencies.

For instance, police can carry out a house search without a court warrant if they have reason to suspect a person to be arrested is inside the premises. People arrested for political actions may also have their personal communication devices seized. After Wong was arrested at Civic Square on September 26, 2014, his phone and computer were taken away and only returned after half a year.

“During this half year, no one knows what they did with my computer and phone. As to whether they could get into my devices, I think it’s not hard to hack into a computer.”

Wong’s examples show how citizens can have their privacy compromised and their communications intercepted. In a bid to protect the personal privacy of Hong Kong citizens, the government has enacted several ordinances, including the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance in 1995 and the Interception of Communications and Surveillance Ordinance (ICSO) in 2006.

The objective of the Privacy Ordinance is to protect the privacy rights of a person in relation to personal data. According to the ordinance, every Hong Kong citizen should follow six data protecting principles when handling personal data. For instance, the collection of data should be done in a lawful and fair way and the people involved should be notified about the purpose of the data collection; personal data should only be used for the data collection purpose; and data users must be open to the public about what types of personal data they hold and how the data is used.

In certain circumstances, such as for the protection of Hong Kong security and in the prevention and detection of crimes, exemptions are allowed. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data (PCPD) is an independent statutory body which oversees the enforcement of the Privacy Ordinance.

While the Personal Data Ordinance was enacted to protect privacy, the ICSO was implemented to regulate the interception of communications and covert surveillance conducted by law enforcement agencies (LEAs), such as the police and customs. The Secretariat, Commissioner on Interception of Communications and Surveillance (SCIOCS) is an independent oversight authority, appointed by the Chief Executive on the recommendation of the Chief Justice.

Under the ordinance, LEAs are required to apply to a panel judge for authorisation to carry out any covert surveillance in cases where there is a higher level of intrusion, for instance when an officer enters a private premises and installs a covert surveillance device. In other cases, LEAs must apply to an authorising officer in their department for the issue of an executive authorisation beforehand.

Although acts of interception and surveillance require authorisation, Lokman Tsui, an assistant professor at the School of Journalism and Communication in the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), says the authorising bodies are often just a rubber stamp. According to the SCIOCS annual report to the Chief Executive in 2015, a total of 1,481 authorisations (including fresh and renewed authorisations) were issued. Only two applications for interceptions were refused. “The office basically approved all requests,” says Tsui.

Michael Mo Kwan-tai, a campaigner (digital communication) at Amnesty International of Hong Kong, says oversight of the ordinance is too weak and can lead to misuse. “There are guidelines, but in practice, how much they comply, you know, is another question,” he says. Mo adds violations of the ordinance constitute civil rather than criminal offences and the penalties have no deterrent effect while the SCIOCS lacks the authority to take follow-up action.

“SCIOCS is a commission but not a department, it is very hard for us to expect them to have such huge capacity like a department to carry out investigations,” says Mo.

CUHK’s Lokman Tsui points out another glaring shortcoming of the ICSO, which is that it does not cover data requests from LEAs to telecommunication companies and internet service providers (ISPs). The ordinance only regulates wiretapping, and the interception and surveillance of communications made through postal mail and the telephone. As it does not cover online communication, citizens have no protection in regard to interception and surveillance on the internet.

In this digital age, people are always using their smartphones to surf the internet, and telecommunication companies have access to users’ personal data such as their browser history, their IP address and geographical locations. Law enforcement agencies are not required to get court warrants before requesting that telecommunication companies hand over their users’ personal data, and it is up to the companies to decide whether to do so.

According to statistics released by the Innovation and Technology Bureau, the police filed 3,448 requests to ISPs for user information in 2016. This is the highest number of requests among all government departments and the main reason given for the requests was crime prevention and detection.

Information on how the government requests user data can also be found in the Hong Kong Transparency Report, published annually by the Journalism and Media Centre at the University of Hong Kong. The report tracks government requests to information communication technology (ICT) companies for their users’ data and for removal of online content, as well as how overseas ICT companies respond to such requests. The 2016 report shows a declining number of data requests to ICTs, from 6,008 in 2013 to 4,637 in 2015. However, the government has sent more requests to social media companies, especially to Facebook which has seen a more than two-fold increase in 2015 compared to 2014.

The report found that overseas ICT companies rejected 40 per cent of the data requests from the Hong Kong government, which accounted for 44 per cent of the total data requests. Benjamin Zhou Suibin, the Hong Kong Transparency Report Project Manager, says LEAs are not legally obliged to provide a court warrant when requesting users’ data. It is wholly up to the company to decide whether to comply. Zhou says overseas companies will release transparency reports annually to disclose how they responded to government requests, but local ISPs do not. He thinks smaller local companies usually just hand over users’ data because they do not have teams of lawyers to evaluate the requests.

The Keyboard Frontline, an internet freedom advocacy group, carried out a project called “Who’s on your side?” in 2015 which reviewed Hong Kong local online service providers’ levels of transparency and respect for user data privacy. Glacier Kwong, the spokesperson for Keyboard Frontline, says “the findings imply that many Hong Kong local ISPs don’t have the awareness to protect users’ personal data.”

Kwong says local ISPs collected excessive data when users register for an account. For instance, to sign up to post on an online forum, users would be asked for details such as their occupation and income as well as their email. Kwong says ISPs have no clear and comprehensive legal guidelines on how to handle data requests from the government.

“If ISPs give users’ data to LEAs upon request every time, LEAs may form a habit of abusing the procedure,” says Kwong, adding that because local ISPs do not release transparency reports on how they handle the government’s data requests, people will never know whether their personal data has been disclosed.

This can have serious consequences for users. For instance, several netizens were arrested for posting comments on Hong Kong Golden Forum encouraging people to take certain actions, such as charging police cordons during the Occupy Movement protests in 2014. Kwong says officers would not have been able to identify the posters unless Hong Kong Golden Forum passed their relevant data to the police. She points out the definition of “public security” in the ICSO is unclear.

“This is very scary. Is it that any form of social activities can be intercepted with this excuse? This will lead to a white terror; it may even affect the Hong Kong’s freedom of speech and assembly,” she says.

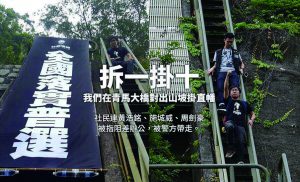

Craig Choy Ki, the convenor of the Progressive Lawyers Group, says the government has abused existing statutes to arrest social activists on laws that were intended for other purposes. For instance, activists have been charged with “access to computer with criminal or dishonest intent” which was originally implemented to handle hacking and computer fraud. Using this law, police can take away activists’ personal computers and mobile phones.

Raphael Wong Ho-ming, vice-chairman of the League of Social Democrats, says there should be laws regulating the confiscation of mobile phones by the police. Wong’s phone was seized while he was filming a policeman who tried to snatch his protest banner during the visit of Zhang Dejiang, the National People’s Congress chairman, last year. He was arrested and his phone confiscated – which he says was an intrusion of his privacy. Wong fears that the police may not have only looked at relevant information but also have wanted “to search for new information to add new charges on me”.

Wong demands that every citizen’s privacy should be protected but he also insists that the government should disclose its information to the public because the public has the right to know.

Indeed, there are two sides to the argument for privacy protection. While privacy advocates argue there is not enough regulatory protection of citizens’ privacy, the government cites the need to protect privacy when it does not want to disclose information.

Mak Yin-ting, a member of the Press Freedom Subcommittee of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, says: “Privacy and the freedom of the press is very unbalanced now, obviously it tends to protect privacy more.” Mak says the government always uses privacy protection as a reason for not disclosing information to the public.

She argues the ordinance regulating interception and surveillance, the ICSO, should include professional privileges for journalistic materials, like legal professional privileges. Mak points to a case revealed in the Surveillance Commissioner’s 2009 annual report, in which the judge allowed law enforcement agents to continue intercepting communications even though they had told the judge that journalistic materials were included in the interception.

“If interviewees know they are being intercepted, then no one dares to tell the truth in the conversation,” she says. “If there is no freedom of communication, will there still be freedom of expression?”

Edited by Rammie Chui