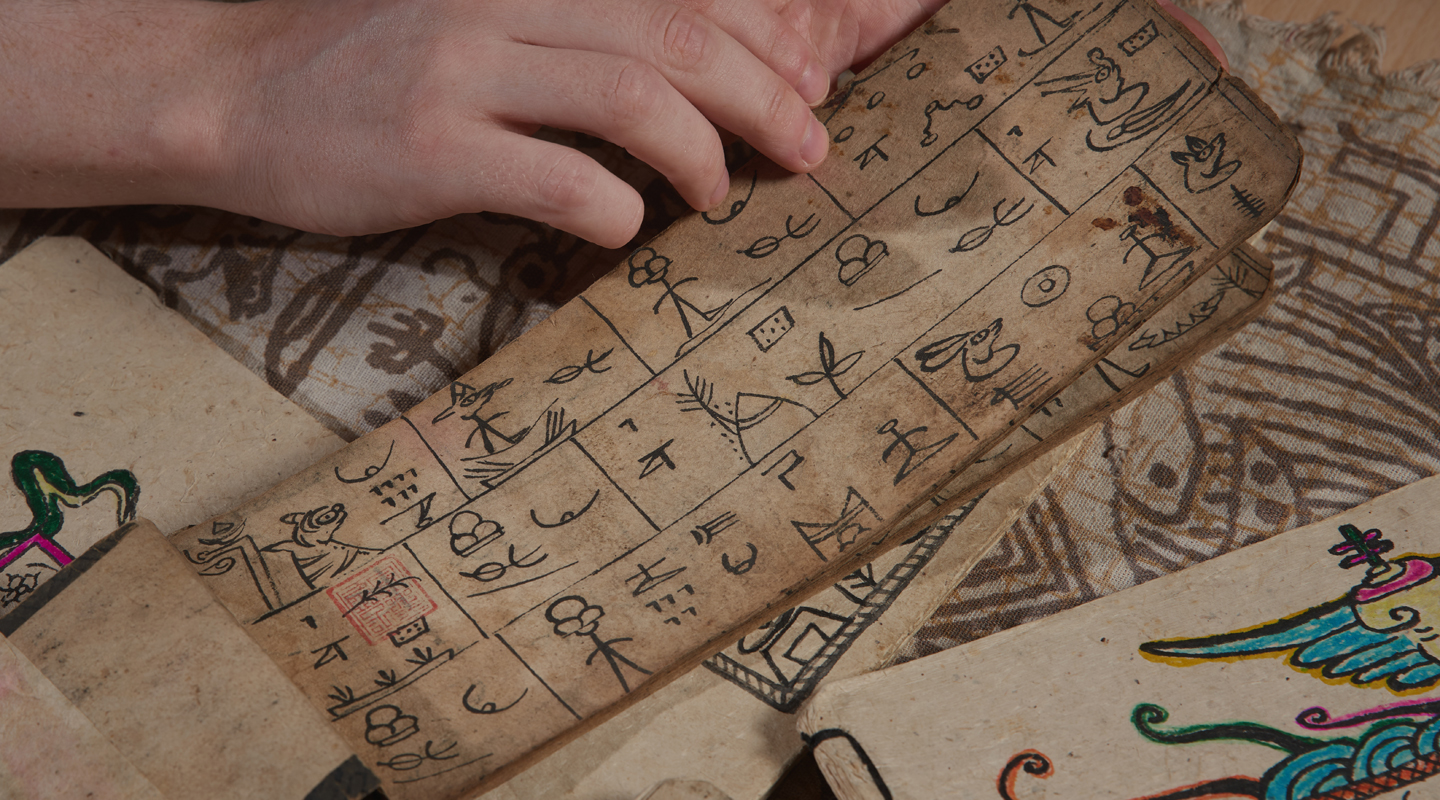

An early 20th century manuscript of the text for the Herkeel ceremony, the Naxi ritual to guide those having committed love suicide to the afterlife, written in the Dongba script

One day, down the eastern end of the Himalayas, the local Naxi people built a fire. It was for those of their children who had killed themselves to escape from arranged marriages, which had become the norm ever since the Qing Empire imposed direct rule on the community and brought in Confucianism. Seated before the fire, crowned, their priest, the dongba, opened a book with rows after rows of drawings of everything from the beasts on the earth to the stars in the sky. The long strings of pictures made no sense to the lay person, but for the priest, it was a message to the young martyrs, a plea he must now chant for their roaming spirits to join their ancestors in the afterlife:

Long, long ago,

When the people lived on the great green earth, they migrated south, down from the high mountains...

But only the adolescent boys and girls, they did not go down.

Then all the stars in the vault of heaven showed them the way down, but the young boys and girls did not follow the path of the stars...

Many years later, the book, begrimed by the ritual fire and worn out after a century of wars and turmoil, found its way to Prof. Duncan Poupard’s office at the Department of Translation. The odyssey of the book through time is in many ways the story of the enigmatic, uniquely pictorial script in which it was written—hoarded by the priests for centuries, suppressed as a relic of a toxic culture, now rediscovered with renewed interest in it. But while the book must end up perishing as its materiality dictates, the professor believes that the writing system, a linguistic miracle, can—and should—live on.

Prof. Duncan Poupard

Named after the priests that once monopolized it, the script, Dongba, is one of the multiple ways to write the Naxi language, a member of the Sino-Tibetan family. Despite its limited use, it has gained some fame for being ‘the world’s last living pictograms’, a system in which, say, the concept of the sun is conveniently denoted by a picture of the solar disc in writing. However, as much as it retains the pictorial look that has now receded in such systems as the Han characters, it does much more than visualizing meanings as Professor Poupard pointed out.

‘There are pictograms in the script, but obviously it doesn’t only have pictograms, because then how do you represent abstract things, a whole lot of verbs and grammar words?’

Indeed, the ways Dongba conveys meanings are varied: from indicating the element of iron metaphorically with an axe , to evoking the action of selling with a thorn , using the fact that the Naxi words for the two have the same pronunciation. It is also common to see compound graphs, where the relatively new idea of a bus, for example, is aptly represented by the existing pictograms of a man , a woman and a wooden vehicle combined .

With its many possibilities, Dongba has proven to be a writing system as viable as it is visually stunning. Though primarily a religious script, it has also been used to write diaries, prescriptions and land contracts. But in any case, it was only the priests who knew how to use it, and being targeted as a medium for superstitions in the Cultural Revolution, during which countless manuscripts were lost, the already endangered script came ever so close to going extinct. It was not until the 1980s that it saw a revival when it became possible for Chinese scholars to study it and it started being capitalized on to boost cultural tourism in Lijiang, the heartland of the Naxi people.

‘After the turn of the century, it was decided that there should be more of the script visible in Lijiang. A proclamation was made, and every shop in the old town was to show a Naxi translation of its name, printed in Dongba,’ Professor Poupard reported. Since then, the script has appeared across a wider region and in more practical situations like a fire safety notice or a sign for a water fountain.

The shopfront of a Starbucks in Lijiang, bearing a phono-semantic Naxi translation of its name at the top of the plaque, engraved in Dongba (Photo by interviewee)

But despite its potential, it is still far from being in vernacular use. Being more of a token or an ornament, it could even be said to be in a state of living death. As with the Han characters, a different word often gets a different symbol in Dongba. Anyone who wants to use the script in everyday life will have to learn around 1,500 of its symbols, and the number goes up to 4,000 if they are to write the names of the many people, places and deities in the culture. This will take years of formal education, the impetus for which is simply lacking.

‘It’s taught as an elective for one or two hours a week, but it’s never going to get into the syllabus, because then the parents would be like, “My child is not going to get a job doing this”,’ Professor Poupard noted.

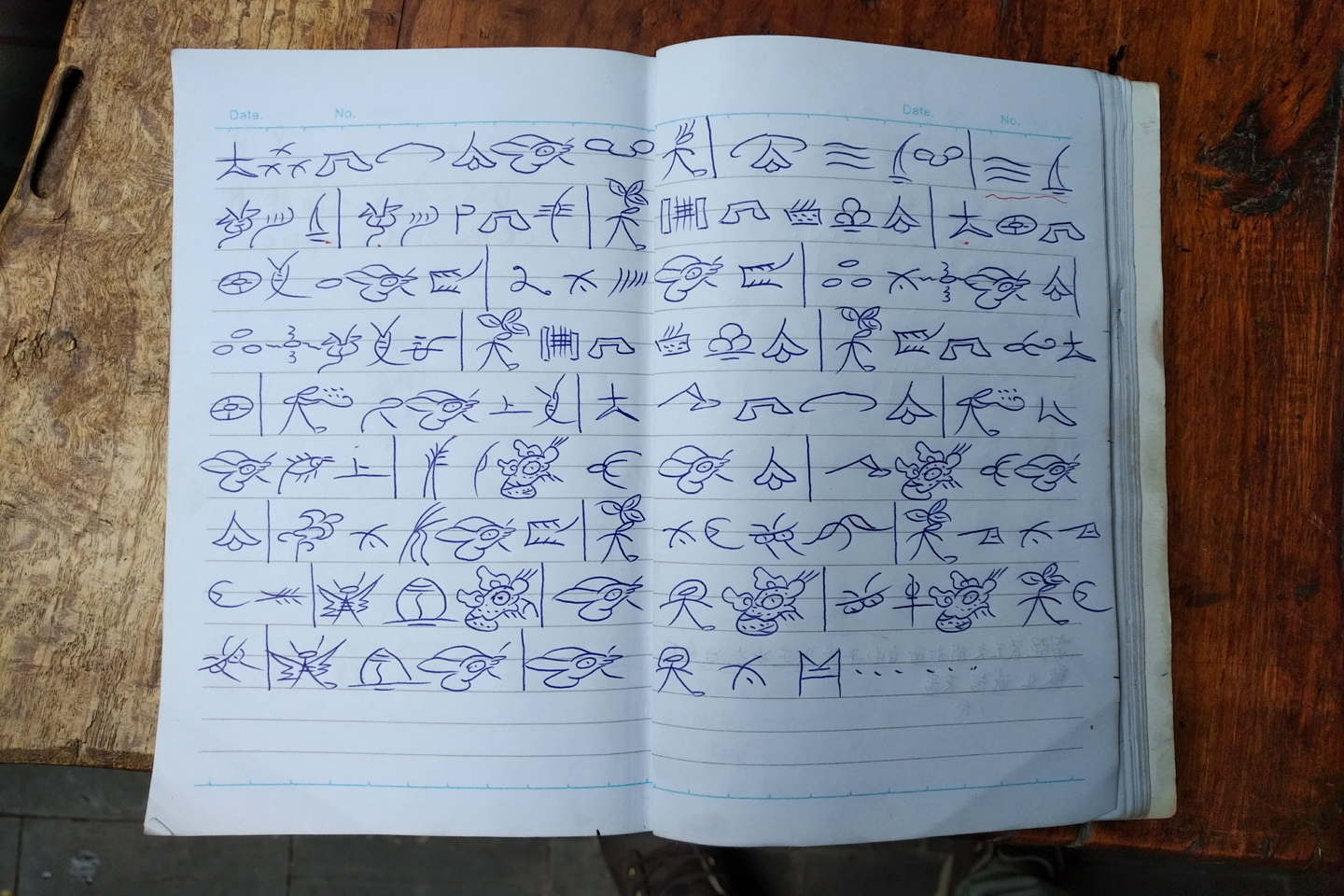

Having said that, there is certainly room for the script to be elevated. Moving aside his prized collection of sacred texts, Professor Poupard showed me a photo of a modern-day notebook belonging to a native Naxi student, inscribed with the lyrics of a popular song in a most graceful Dongba script. Perhaps this is what the writing system can aspire to be for now, a tool for self-expression, and to that end, Professor Poupard is going out of his way.

‘I wrote an article about revitalizing the script as a vernacular last year, and I decided that if I’m serious about this, I should reach out to a wider audience rather than just writing for a journal that only 10 people will read,’ he said with a laugh. And so he has teamed up with an exhibition centre in Lijiang to produce video lessons teaching the basics of the script while preparing for a public showcase in London of his British Academy-funded research, where he intends to have a dongba priest do some simple recitations and give visitors a taste of the script by demonstrating how to write their names with it. Ultimately, though, he thinks the script’s future comes down to whether there is a way to type it.

‘We need to be able to input it easily on modern devices, which means it needs to be encoded in Unicode,’ he said. ‘Hopefully this will happen at some point, and then we can get an input method, possibly a phonetic one.’

A local Naxi student's notebook with the lyrics of a popular song in Dongba (Photo by interviewee)

One might wonder why we should care if such a marginal writing system is alive and well. Apart from being a religious tool and inspiring arts and crafts locally and abroad with Ezra Pound using it in his Cantos, the script is in itself a cultural treasure trove. In the Dongba character for rherqngvlv , the word for the windy snow mountain watching over the Naxi, the summit is depicted with a mouth letting out a cry. Beyond being a neat artistic trick, the personification may well be a window into the way the Naxi view nature, one that is lost if the script is gone.

But at the end of the day, the love of the script or, indeed, any language is perhaps a love that needs no reason. It was this natural affinity for what is ‘different’, in his own word, that first got Professor Poupard into Mandarin, took him from York to Zhejiang after university and immersed him in a Dongba text for the first time during a summer trip to Lijiang. The same should go for all of us. There is after all something to be celebrated about the fall of Babel—the very fact that there is a diversity of languages and scripts—for it is these many fires, cropping up as far as in the Himalayas and as near as at home, feeble as they might be, that give the world its splendour.

ISO, CUHK

By jasonyuen@cuhkcontents

Photos by Keith Hiro